Jaya Hé! The Story of India’s National Anthem

Writers whose compositions become the national anthem of their country surely regard this as a supreme honour. But what if you are the author of the national anthems of two sovereign independent nations? Rabindranath Tagore, poet, musician, writer, artist and polymath who remodelled Bengali literature and music, was such a one. His song Amar Shonar Bangla [My Golden Bengal] is Bangladesh’s national anthem, and Jana Gana Mana (the focus of this essay) is India’s. But when Tagore, the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize for Literature passed on in 1941, he had no idea that two of his songs would become national anthems and part of his legacy.

A poem becomes a song

Tagore set his poem (virtually a hymn) that eventually became India’s national anthem to music, and it was first sung at the annual meeting of the Indian National Congress in Calcutta on Dec 27, 1911 in a chorus led by Sarala Debi Chaudhurani, Tagore’s niece, in the presence of the Congress President Bishan Narayan Dar, and other leaders such as Ambika Charan Mazumder and Bhupendra Nath Bose. The next month, the poem appeared in print under the title Bharat Bhagya Bidhata in ‘Tattvabodhini Patrika,’ the journal of the Brahmo Samaj. Today it is almost exclusively known by its opening phrase, Jana Gana Mana, and henceforth will be referred to by that name.

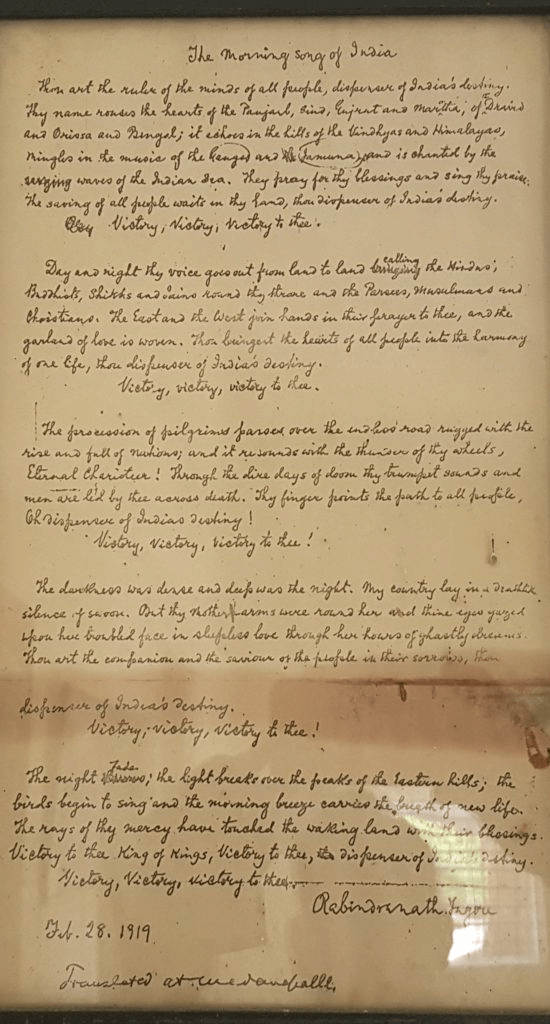

It took another eight years for the music of Jana Gana Mana to be standardized. In 1919, the Irish poet and Indophile James H. Cousins, vice-principal of Theosophical College in Madanapalle (a town in Chitoor district in the present-day state of Andhra Pradesh) invited his friend Tagore for a short stay. Every Wednesday, Cousins and his wife Margaret would hold an informal after-dinner assembly with the students and teachers. On February 28, 1919, Tagore joined the assembly and with some prodding by Cousins, sang Jana Gana Mana. It moved the audience. Tagore’s singing voice, Cousins said, was “surprisingly light” for so large a man. Cousins recollected: “The refrain to the first verse made us prick our ears. The refrain to the second verse made us clear our throats. We asked for it again and again, and before long we were singing it with gusto… Jaya hé! Jaya hé!” The college adopted it as their prayer song.

Tagore must have been pleased. This was a college, and education was dear to his heart, though he loathed the formal system with its lectures, notes, tests, ranks and grades. His philosophy was: Good teachers don’t explain things. They instil curiosity in their pupils. He had founded the Visva-Bharati University on his ancestral Shantiniketan estate in Bengal on such principles, donating his entire Nobel Prize earnings to the university. So it was, well, poetic, that students and teachers were the first Indians to sing Jana Gana Mana with the Bard of Bengal himself leading them. Stirred by the reception, Tagore translated the song into English, calling it “The Morning Song of India.”

Margaret Cousins transcribed the melody onto paper in Western music notation. It was important to formalise the tune, she gently informed Rabi (as his family and close friends called Tagore), otherwise people would sing it any which way they wanted, and a distorted tune wouldn’t do this great song full justice. She asked Tagore to elucidate the meaning of each line and, using his tune as the base, rewrote the music to extract the best cadence. As she held a degree in music from the Royal University of Ireland in Dublin, she could follow Tagore’s desire for his preferred swara sargam (note sequence) composed in Raga Alhaiya Bilawal. Tagore left Madanapalle with the sheet music of Jana Gana Mana in his hands.

Margaret Cousins’ melody is more or less followed to this day, but her notation is slow and reflective, the way Tagore sang it. Today the anthem is played at a speedy tempo; the music is bouncy. The faster arrangement is the handiwork of Herbert Murrill, Professor of Composition at the Royal Academy of Music, London. Murrill, at the request of India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, changed the sedate hymnal into a martial march in the style of the French national anthem La Marseillaise ─ it can be performed in under a minute.

Audio & Visual: https://musescore.com/nakuljogdeo/scores/4437636

Sheet music of Jana Gana Mana arranged for solo piano by Nakul Jogdeo. The ‘play’ button at the top left of the page activates an audio recording. Using the “Playback Speed” icon (the bell shaped icon representing a metronome, with +and – buttons alongside) located above the score, you can make the music sedate like the Cousins version or swift like the Murrill version.

Jana Gana Mana (“Cousins Version”) played by the Bundesjugendorcheste [National Youth Orchestra of Germany] in Chennai, 2018. Conductor: Hermann Bäumer

Jana Gana Mana (“Murrill Version”) played by The South Asian Symphony Orchestra, 2019. Conductor: Alvin Seville Arumugam

The roots of Jana Gana Mana

To better understand the foundations of Jana Gana Mana, we must foray into the past. In 1857, the British encountered the first large-scale rebellion against their colonial rule: a sustained uprising by the Indian soldiers in their army, now called the Sepoy Mutiny. Thereafter, the unnerved British suppressed anything that even remotely seemed a threat to their control. When Bengal became a stronghold for the nationalist movement, the Viceroy of India, Lord Curzon, split the province into two in 1905: East Bengal, with a predominant Muslim population, and West Bengal, predominantly Hindu. The official reason was that two smaller provinces could be administered more efficiently than one large province. But the unofficial sentiment was: Let the Hindus of the West and the Muslims of the East expend their energy knocking the stuffing out of each other, and they will have neither sweat nor stamina left to confront the British.

A direct offshoot of Bengal’s partition was the Swadeshi movement which derived its name (from the Sanskrit swa, own or self, and desh, country) because it boycotted British goods. Western clothing was hurled into communal bonfires, imported grain or sugar or anything from the West became taboo. The protestors gave up their Anglicized surnames – Banerjee, Chatterjee, Mukherjee – in favour of the Bengali originals, Bandhopadhyay, Chattopadhyay, Mukhopadhyay. The swadeshis derided Tagore for not changing his surname back to Thakur. There were protest marches, meetings, demonstrations and petitions to arouse public opinion. But those intensely loyal to the British Crown felt that the British Raj was the best thing that could have happened to India. Thus there were the nationalists and the loyalists. And then, there was Rabindranath Tagore.

Tagore was a rising star in Bengal at the time, but a controversial one. He was no loyalist; he opposed imperialism and espoused nationalism in his first politically charged poems in the collection Manast, written in his twenties. But he did not blindly support movements like the Swadeshi, taking exception to parts of their ideology. He satirized them in his articles and poems even as he wrote songs fervently championing the cause of Indian independence that they espoused. This caused no end of bewilderment: whose side was Tagore really on?

In Chitto Jetha Bhayshunyo (“Where the Mind is Without Fear,” the 35th poem in his collection, Gitanjali), Tagore wrote: “where the world has not been broken up into fragments by narrow domestic walls.” Tagore didn’t coin that because it sounded cute. He believed in universality, in imbibing the best ─ whether it came from within the country or from outside its borders. This clashed with the outlook of the swadeshis: “true” Indians necessarily had to embrace everything Indian and summarily reject anything from the West. Their attitude would be famously summed up by a 21st century American president, George W. Bush, in November 2001: “You’re either with us, or you are against us.”

In 1909, Tagore published his prose masterpiece, the novel Gora. “Gora” loosely translates to “Fair Face” or, if you prefer slang, “Whitey.” ‘Gora’ is the diminutive of Gourmohan, the name of the novel’s protagonist, who is fair in complexion. The sprawling saga tackles a spectrum of issues: religion and fanaticism, society versus the individual, dynamics between the conqueror and the conquered, the role of women, orthodox religion (Hinduism) versus reformist religion (Brahmo Samaj) versus other faiths (Christianity, Islam), love and courtship across cultural obstacles, interplay between power and justice, the nature of patriotism, and the question of identity.

Within his narrative’s magisterial sprawl, Tagore raised issues such as these: Is “political freedom” synonymous with “freedom”? Besides the stone and mortar of the hated British jails, aren’t there other walls that imprison you? And did the British erect all of these confining “narrow, domestic walls”? Some of them? Any of them? If they didn’t, then who was responsible? These were uncomfortable and unsettling questions. But if such dissections disquieted the populace, they spooked the swadeshis. The swadeshis did not know what to make of the character Gora, who stoutly defended India’s traditions and customs against loyalists who collaborated with the Empire, but then whirled around and attacked those very customs when he confronted nationalists who followed them with a blind rigidity. The swadeshis were clueless about handling mavericks, and Gora’s author was a maverick with a capital M.

At the novel’s climax, Gora discovers that he is not the biological child of the Indian couple he regarded as his dear parents. He is the adopted child of Irish parents who died during the Sepoy Mutiny. His universe explodes in one heart-wrenching moment. His notions of patriotism, identity, culture, and personal beliefs, are turned on their head. Who is he? A spawn of the oppressor race who would never accept him as one of theirs? Tagore shows us Gora’s turmoil: “He had no mother, no father, no country, no nationality, no lineage, no God even… what could he hold on to?”

Then, the epiphany. When Gora discovers that he was never born a Hindu, he suddenly revels in a newfound freedom. All the preconditions that he has imposed on himself and on people around him evaporate into the stratosphere, and he feels that he belongs equally to everyone with no binding rules to obey. “Today, I have truly become an Indian. Within me, there is no longer any conflict of communities, whether Hindu, Muslim or Christian. Today, every caste of India is my caste, the food of all is my food!” And: “Because I loved India better than life itself, I was quite unable to bear the least criticism of that part of it which I had got to know. Now that I have been delivered from those fruitless attempts…. I feel that I am alive again.”

An emperor’s double coronation

Even as Gora was being read and hotly debated in the parlours of Calcutta and along the country lanes of Bengal, faraway on another continent, other events were unfolding. Beneath the sunless sky of London, George V had succeeded his father Edward VII to the throne, and, like other British kings, was formally crowned in Westminster Abbey in the summer of 1911. He then surprised everybody by demanding a second coronation. He wasn’t merely the king of a dinky little island in the North Sea, was he? No Siree, he was ruler and overlord of the mightiest empire the planet had known. The jewel in that empire’s crown was India, and he would have a separate coronation there with all the pomp, splendour and spectacle that only India could provide: sitars and tablas, camels and elephants and peacocks, silk and sunshine, and the night lit by more oil lamps than there were stars in the sky. The world would see, the world would know, and the world would prostrate in homage.

As the British armada entered the Arabian Sea, its flagship HMS Medina bearing the maharajadhiraja (King-Emperor) signalled that it would dock in Bombay harbour on December 2, 1911. All of India was fired up. But although Calcutta was the capital of British India, the coronation occurred in Delhi, the seat of many ancient Indian empires. What’s more, the King-Emperor proclaimed that Delhi, not Calcutta, would now be India’s capital. Calcutta had heartburn – but the King-Emperor also issued a royal decree annulling the 1905 partition of Bengal by Viceroy Curzon. As it turned out, the reunification of Bengal would not last long, but people didn’t know it at the time. Calcutta perked up; to a degree, this welcome development offset its loss of status.

Jana Gana Mana – profane or profound?

It was against this tense and volatile backdrop that Jana Gana Mana was sung on December 27, 1911, the second day of the Indian National Congress convention in Calcutta. The Congress party was largely loyal to the Crown. Gandhi was still in South Africa — it would be four more years before he returned to India permanently, and a few more before he changed the Congress’s thinking and launched the independence movement. The Congress enthusiastically dedicated the second day of their convention to honour the King-Emperor who had benevolently reunified their partitioned golden Bengal. Later that day, a song in Hindi, Badshah Hamara (‘Our Emperor’) was sung. Its lyrics were penned by Rambhuj Dutt Chaudhury, the husband of Sarala Debi Chaudhurani, Tagore’s niece, who had earlier sung her uncle’s Jana Gana Mana. All in the family, huh? — some journalists rapidly added two and two to make four and three quarters. Asim K. Duttaroy, a professor at the University of Oslo, Norway, researched what the newspapers had said. Here is the British-Indian press:

“The Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore sang a song composed by him specially to welcome the Emperor.” (The Statesman, Dec 28, 1911)

“The proceedings began with the singing by Rabindranath Tagore of a song specially composed by him in honour of the Emperor.” (Englishman, Dec 28, 1911)

“When the proceedings of the Indian National Congress began on Wednesday 27th December 1911, a Bengali song in welcome of the Emperor was sung. A resolution welcoming the Emperor and Empress was also adopted unanimously.” (Indian, Dec 29, 1911)

Not only did they misinterpret the poem, they misreported the facts: it was Tagore’s niece and not Tagore who had sung Jana Gana Mana. The Indian press had a somewhat different take:

“The proceedings of the Congress party session started with a prayer in Bengali to praise God (Song of Benediction). This was followed by a resolution expressing loyalty to King George V. Then another song was sung welcoming King George V.” (Amrita Baazar Patrika, Dec 28, 1911)

“The annual session of Congress began by singing a song composed by the great Bengali poet Ravindranath Tagore. Then a resolution expressing loyalty to King George V was passed. A song paying a heartfelt homage to King George V was then sung by a group of boys and girls.” (The Bengalee, Dec 28, 1911)

And the 1911 annual report of the Indian National Congress makes a clear demarcation:

“On the second day (of the annual meeting) the work began after singing a patriotic song by Babu Ravindranath Tagore. Messages from well wishers were then read and a resolution was passed expressing loyalty to King George V. Afterwards the song composed for welcoming King George V and Queen Mary was sung.”

Tagore himself maintained a dignified silence following the attacks in the press. His patriotism was patent. Why strengthen his detractors by fuelling their baseless charges with his responses? Only a blithering idiot would mistake Jana Gana Mana for God Save the King. But he greatly underestimated how many such idiots were milling around. On hindsight, perhaps he should have spoken up, for some of the mud flung at him has stuck, even after a hundred years. The controversy must have rankled, because Tagore brought the matter up through two letters written in the last years of his life.

Part of the problem may have been that a friend who worked for the government tried to cajole Tagore into writing a paean to the King-Emperor, and that piece of news could have circulated. On November 10, 1937 Tagore wrote a letter to Pulin Bihari Sen, the head of Visva-Bharati University’s publication division. The text of that letter (in Bengali) can be found in Tagore’s 1946 biography, Ravindrajivani by Prabhat Kumar Mukherjee:

“A certain high official in His Majesty’s service, who was also my friend, had requested that I write a song of felicitation towards the Emperor. The request simply amazed me. It caused a great stir in my heart. In response to that great mental turmoil, I pronounced the victory in Jana Gana Mana of that Bhagya Vidhata [Dispenser of Destiny] of India who has from age after age held steadfast the reins of India’s chariot through rise and fall, through the straight path and the curved. That Lord of Destiny, that Reader of the Collective Mind of India, that Perennial Guide, could never be George V, George VI, or any other George. Even my official friend understood this about the song. After all, even if his admiration for the Crown was excessive, he was not lacking in simple common sense.”

And in a letter dated March 19, 1939, quoted in the literary journal Purvasha, Tagore stated his position in unequivocal terms:

“I should only insult myself if I cared to answer those who consider me capable of such unbounded stupidity as to sing in praise of George the Fourth or George the Fifth as the Eternal Charioteer leading the pilgrims on their journey through countless ages of the timeless history of mankind.”

If you want to ingratiate yourself with somebody, it helps if your target understands your flattery. George V could not distinguish Bengali from Tamil, Marathi, or gobbledegook. If Tagore wished to grovel before the King-Emperor, wouldn’t he have composed his paean in English, of which language he was a consummate master?

Tagore’s full composition of Jana Gana Mana (all five verses in Bengali) sung by Swagatalakshmi Dasgupta.

Jana Gana Mana – a literary masterpiece

A century later, there are still Indians who charge that their fellow countrymen and countrywomen continue to blindly sing a song extolling colonialism, and that Tagore’s patriotism is suspect. They point to lines such as these to support their position.

In the first verse:

…adhināyaka jaya hé, Bhārata bhāgya vidhātā.

Victory to the Ruler, Dispenser of India’s destiny.

In the second verse:

…suni tava udār vāni,

Hindu, Bauddh, Shikha, Jain, Parasik, Musalmān, Khristāni;

Purab Paschim āsé, tava simhāsana pāsé.

In response to thy gracious call

The Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs, Jains, Parsis, Muslims, and Christians,

From the East and from the West, they gather together before Thy throne.

In the last verse, at the crescendo:

Jaya jaya jaya hé, jaya Rājeshwara, Bhārata bhāgya vidhātā

Victory, Victory, Victory to thee, O Supreme Ruler-Lord, Dispenser of India’s destiny.

What is overlooked is that Tagore employs the imagery of an earthly king and the power he wields to denote a higher power or the power innate within one’s higher self. (Tagore used the same metaphor in many of his poems. Poems 50 and 51 in Gitanjali are good examples.)

There is also selective picking. Critics ignore lines that don’t fit into the ‘Hail to the King-Emperor’ theory. Take for instance, these lines from the third verse:

Patana abhyudaya vandhura pantha, yuga yuga dhābit yātri

Hey chira sārathi, tava ratha-chakrey mukharit patha din rātri

Dārun viplab mājhey, tava shankha dhwani bājey

Down the ages we, the pilgrims, have trod the rugged road of life with its ups and downs,

O Eternal Charioteer! The sound of your chariot wheels echo night and day

And the boom of your conch shell reverberates in the midst of our revolution.

This was the passage Tagore referred to in his 1939 letter. Pilgrims aren’t interested in earthly kings; their quest is spiritual. And while it is conceivable the British emperor could be poetically compared with a ‘charioteer,’ he (or any other mortal monarch) could scarcely be considered ‘eternal.’

But those lines conjure the image of the Hindu deity Krishna who served as Prince Arjuna’s charioteer in the internecine civil war in the epic, The Mahabharata. Krishna is not named; Tagore the poet leaves the interpretation of the charioteer symbol to his readers, some of who interpret it as “perennial guiding spirit.” Just as striking is the image of the sounding of the conch shell (shanka dhwani). The conch is blown like a trumpet in certain religious ceremonies such as the consecration of a new temple, but in ancient India it was blown during a war, especially to herald the start of a war – a detail Indians are familiar with from the recounting of many stories. For example, the Mahabharata War began after Krishna blew his conch.

So what is the war that Tagore alludes to, even using the word viplab, revolution? The obvious answer: the war against British imperialism. The phrase Nidrito Bhārat Jāgey (Awaken, slumbering India), so neatly tucked into in the last verse, was a coded phrase, a favourite of activists demanding the end of British rule. Far from licking George V’s boots, Tagore’s ultimatum was the exact opposite: boot him out! It was a daring message, cleverly cloaked in two potent weapons in a poet’s armoury: metaphor and double-entendre.

Our understanding of Jana Gana Mana is considerably deepened if we have read Tagore’s work that preceded it: his novel, Gora. Gora finds his identity only after first losing what he had believed to constitute his identity. That is Tagore’s challenge to his fellow Indians. Liberation from foreign rule was a battle, but the larger war wouldn’t and couldn’t be won until those other walls that imprisoned society were also battered down.

Do you speak in Assamese or Malayalam? Do you prefer chapatti or rice? Do you drape the end piece of your sari over your right shoulder or your left? Do you perform namaz, wave the lamp for ārati, cross yourself as you accept the wine and wafer, or subscribe to no religion? Do you ride the train, drive a car or scooter, use a bullock cart or walk? Do you wear trousers or a lungi, or both, or neither? Do you make a beeline for tandoori chicken or shorshe ilish, or are you as vegetarian as you can possibly be? Do you take your tea with aromatic spices like cardamom or take it plain, or perhaps you only care for hot ‘filter’ coffee? Do you don a turban, a skull cap, or go about bare-headed as well as bare-footed? Who do you prefer to hang out with in your free time? Such things define who you are within a diverse and multifaceted India.

But if you transcend such markers (not jettison them, but transcend them), then on that lofty plane you will come face to face with the primal ruler (adhināyaka) who dispenses India’s destiny (Bhārata bhāgya vidhātā). Rest assured that this entity is neither George V nor his ghost.

In keeping with his expansive worldview, Tagore interpreted the Vedic dharma (duty, virtue, righteous living) as having many components ─ for dharma is applicable to all humans and the human race is kaleidoscopic. For example, there is family dharma: one’s duty and responsibility as husband or wife, parent or child, brother or sister, and so on. Then there are obligations to the community that one lives in. But besides these kinds of dharma, there was a higher dharma, Sādhārana Dharma (“Universal Dharma”) which transcended one’s individual situation, caste and other identities, group affiliations, and other boundaries; it was applicable to all. The Hindu scripture Mahopanishad summarizes this form of dharma through the Sanskrit phrase Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam or “The world is my family” (vasudha = the earth [and its inhabitants], eva = is indeed, kutumbakam = my family; Mahopanishad VI: 70-73). It was this form of dharma that Tagore invoked in his all-encompassing Jana Gana Mana.

From poem to song to national anthem

On August 15, 1947, India became independent from British rule and opted to become a republic, with a constitutional president elected by its Parliament to replace the British monarch as Head of State. It took about two and a half years for the constitution of the new nation to be drafted and then formalized by the Constituent Assembly. It came into force on January 26, 1950 (which date is now commemorated as India’s Republic Day).

The new republic needed a national anthem, and there were three contenders: Tagore’s Jana Gana Mana, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s Vandé Mātaram, and Muhammad Iqbal’s Tarana-é-Hind (popular title: Sāré Jahan Sé Acchā). The Constituent Assembly narrowed its choice to the first two.

Vandé Mātaram (Mother, I Salute Thee) was originally a poem in Chattopadhyay’s 1882 novel Ananda Math (The Monastery of Bliss). This poem was set to music by none other than Rabindranath Tagore, who first sang it at the 1896 annual convention of the Indian National Congress. “Vandé Mātaram!” became a rallying cry of the independence movement, defying the British who banned its public utterance. So there were strong sentiments backing this song to become the national anthem.

At independence, India was carved into two nations. Pakistan was birthed as an Islamic nation but India opted to be a secular republic that conferred equality on citizens of all religions, recognizing that diversity conferred strength. Many preferred India to have Hinduism as its state religion the way Pakistan embraced Islam. The ideological divide persists to this day and will continue into the foreseeable future. In the Constituent Assembly, those who wanted a Hindu state backed Vandé Mātaram.

The first two stanzas of Vandé Mātaram equate “Mother” with “Motherland.” But a later stanza specifies the term “Mother” with the Hindu goddess Durga. The Constituent Assembly felt this would not fit a secular India with numerous religious minorities who would be expected to sing and respect the anthem. The Assembly decided that while Vandé Mātaram (and Ananda Math) had an undeniably permanent niche in Indian literature and the independence movement, and while the lyrics of Vandé Mātaram fitted the context of the novel and the setting of Bengal where Durga is a beloved deity, Jana Gana Mana was more appropriate as the anthem for a diverse republic. On January 24, 1950 the Assembly adopted the first verse of Jana Gana Mana as the national anthem and the first two verses of Vandé Mātaram as the national song, according them equal status.

But those rooting for Vandé Mātaram weren’t buying it; the national song clearly played second fiddle to the national anthem. And over the years, the push to replace Jana Gana Mana keeps cropping up. Now, people of an ideological persuasion will press their agenda; this is true not just for India but for all countries. But in the process, they keep rubbishing Tagore, casting slurs on his patriotism, accusing him of treachery. I am not implying that Tagore is above criticism (he isn’t) or that his life was flawless (it wasn’t) but in this particular case, the continued character assassination is repugnant. In 2011, a private school in Uttar Pradesh even re-wrote the anthem believing it to refer to the British monarch and made their students memorize and sing the altered version.

A fresh controversy erupted in 2005 when a petition was filed in India’s Supreme Court to delete “Sindh” from the anthem as that province now belonged to Pakistan. Sindh should be replaced by Kashmir, the petitioners argued. The underlying motive was patent – both India and Pakistan were in dispute over Kashmir, and its inclusion in India’s national anthem would signal where Kashmir belonged. One of the counter-arguments to the petition was that Jana Gana Mana wasn’t about geography; it was about people, right from the opening words (Jana Gana Mana, the minds of the people). Sindh might now be in Pakistan, but there were thousands of ethnic Sindhis who lived in India and were Indian to the core. The Supreme Court agreed, and Tagore’s composition stands.

Listen to the anthem

This video was created for the 50th anniversary of the Republic of India.

The first part consists of an orchestral rendition of Jana Gana Mana by some of India’s finest musicians: Hariprasad Chaurasia, Amjad Ali Khan, Shiv Kumar Sharma, Vishwa Mohan Bhatt, E. Gayathri, Ravikiran, Kadri Gopalnath, Kartick Kumar, Niladri Kumar, Amaan Ali Bangash, Ayaan Ali Bangash, Uma Shankar, the Kumaresh & Ganesh duo, and several others. The orchestra, led by K. Srinivas Murthy, consists of a number of instruments: sitar, sarod, flute, ghatam (yes, earthen pots), santoor, violin, veena, mohan veena, chitra veena, sarangi. The conductor is A. R. Rahman. The pure notes of Tagore’s melody come through Rahman’s arrangement, which is closer to the Tagore/Cousins original than it is to Murrill’s martial march.

In the second part, the anthem is sung by some of India’s finest vocalists, solo and in chorus, from resonant bass to vibrant soprano, including Lata Mangeshkar, D.K. Pattammal, Bhimsen Joshi, Jagjit Singh, Balamuralikrishna, Jasraj, S.P. Balasubramaniam, Asha Bhosle, Bhupen Hazarika, Kavita Krishnamurthi, Saddique Khan Langa, Parveen Sultana, and many more.

Jana Gana Mana (the National Anthem of India)

Jana-gana-mana adhināyaka jaya he

Bhārata bhāgya vidhātā

Pañjāba Sindh Gujarāṭa Marāṭhā

Drāviḍa Utkala Baṅga

Vindhya Himāchala Yamunā Gaṅgā

Ucchala jaladhi taraṅga

Tava śubha nāme jāge

Tava śubha āśiṣa māge

Gāhe tava jaya gāthā

Jana gaṇa maṅgala dāyaka jaya he

Bhārata bhāgya vidhāta

Jaya he, jaya he, jaya he

Jaya jaya jaya, jaya he

Thou art the ruler of the minds of the multitudes,

Thou, Dispenser of India’s destiny.

Thy very name arouses the hearts of Punjab, Sindh, Gujarat and Maratha

Of the Dravida regions, and of Orissa and Bengal;

It echoes in the hills of the Vindhyas and the Himalayas,

Mingles in the music of Yamuna and Ganga, and is

Chanted by the waves of the Indian Ocean.

They pray for thy blessings even as they sing Thy praise

For in Thy hand lies the saving of the people,

Thou, dispenser of India’s destiny.

Victory, victory, victory to Thee.

For those who would like more:

- The Voice of Rabindranath Tagore: Audio recording of Tagore reciting the first verse of Jana Gana Mana http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0XaWGZRHMRQ.

- Ensemble performance of Jana Gana Mana (https://youtu.be/6xwWRPXfJk0)

0:01 Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia (Flute) 0:05 Pandit Shiv Kumar Sharma (Santoor) 0:08 Pandit A. Ananthapadmanabhan (Veena) 0:15 Dr. N. Rajam (Violin) 0:18 Ustad Amjad Ali Khan (Sarod) 0:23 Pandit Vikku Vinayakram (Ghatam) 0:27 Ustad Shahid Parvez Khan (Sitar) 0:31 Pandit Vishwa Mohan Bhatt (Mohan Veena) 0:35 Ustad Zakir Hussain (Tabla) 0:42 Pandit Rakesh Chaurasia (Flute) 0:44 Ustad Dilshad Khan (Sarangi) 0:46 Dr. Sangeeta Shankar (Violin)

- Two group instrumental renditions of the anthem, the first on guitars and flute (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G6Hxk5gfpVU), the second played by a strings quintet: two violins, and a viola, cello, and bass. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BMtJdQQ2yNo)

- Solo rendition of Jana Gana Mana on the harp (https://youtu.be/7o8pVMaJCio)

- Solo rendition of Jana Gana Mana on the saxophone (https://youtu.be/G0941H-0fwU)

- Solo rendition of Jana Gana Mana on the sitar (https://youtu.be/f0gQfsYYbo8)

- Solo rendition of Jana Gana Mana on the shehnai (https://youtu.be/7PFcnv_waeo)

- Jana Gana Mana played on a set of tablas (https://youtu.be/X0S9WV9NvIE)

- Solo rendition of Jana Gana Mana on the jalatarang (https://youtu.be/CQQ6Qp-07TA)

- Across international borders: The Canadian High Commission in India invited Canadian singer and Indophile, Natalie Di Luccio, to sing Jana Gana Mana at their Canada Day celebration, echoing the universality dear to Tagore. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uF_TYGpu2L4