Is thumri louche or evolved? 100 years on, a debate around the classical form still rages

If music were charted on a gender spectrum, popular theory has it that the dhrupad would fall on the masculine end and the thumri feminine, with the khayal somewhere on the continuum but tending towards the masculine. This would explain why the thumri has been at the heart of some of the most vivid feminist debates on women’s agency in performing arts.

With its themes of longing, separation, and subtle and overt eroticism, who is the coquettish thumri addressing? Once the domain of the tawaifs, is it pandering to the male gaze, per classical feminism, or is it allowing a woman the freedom to speak her heart? Is it louche or is it highly evolved? How do we see its indulgent references to chhed khaani, or teasing, as young artistes have recently argued? These and other questions around the thumri have been argued for about 100 years now.

Tracing the history of these arguments is almost like tracing the history of feminism. And no one is better placed to look back and ahead than thumri singer, scholar and feminist Vidya Rao, whose 1990 paper “Thumri As Feminine Voice” in the Economic and Political Weekly set off fiery debates.

“When I first expressed an interest in seriously pursuing thumri, many people felt this was not a subject central to feminist studies or for feminists to concern themselves with,” said Rao of her foray into thumri in the 1980s. “In the world of music too, thumri was, at that time, still to gain full acceptance as a worthy ‘classical’ form.”

Like feminists, patriarchy too had rejected the thumri. Rao’s own guru, Naina Devi, had to abandon her pursuit of the form for decades after she married into a royal family because of the stigma around it. In later years, in her widowhood, she returned to the thumri, becoming one of its finest exponents, teachers and evangelists. Her story – well-documented by her family and Rao in her book Remembering Nainaji – speaks of how she enhanced her repertoire by listening to and encouraging the baijis from behind a purdah at family mehfils.

Surat mori kahe bisrai, Siddheshwari Devi

What exactly is the thumri? Derived from folk forms (desi) of the purab (east), and based on what ethnomusicologist Peter Manuel calls a “short amatory text with devotional overtones”, it revels in rasa or emotions rather than strict raga rendition as is the case with the khayal or dhrupad. The lilt, themes and pace make the thumri more accessible.

Thumri singers will tell you that the art is as much about mizaj (temperament) as skill. With a lot more mood-building drama built around its music, the thumri is packed with ornamental elements that allow all kinds of vocal histrionics. Primary among these is the distinctive pukar (a plaintive musical cry to express grief, pleading) that goes into the thumri’s making.

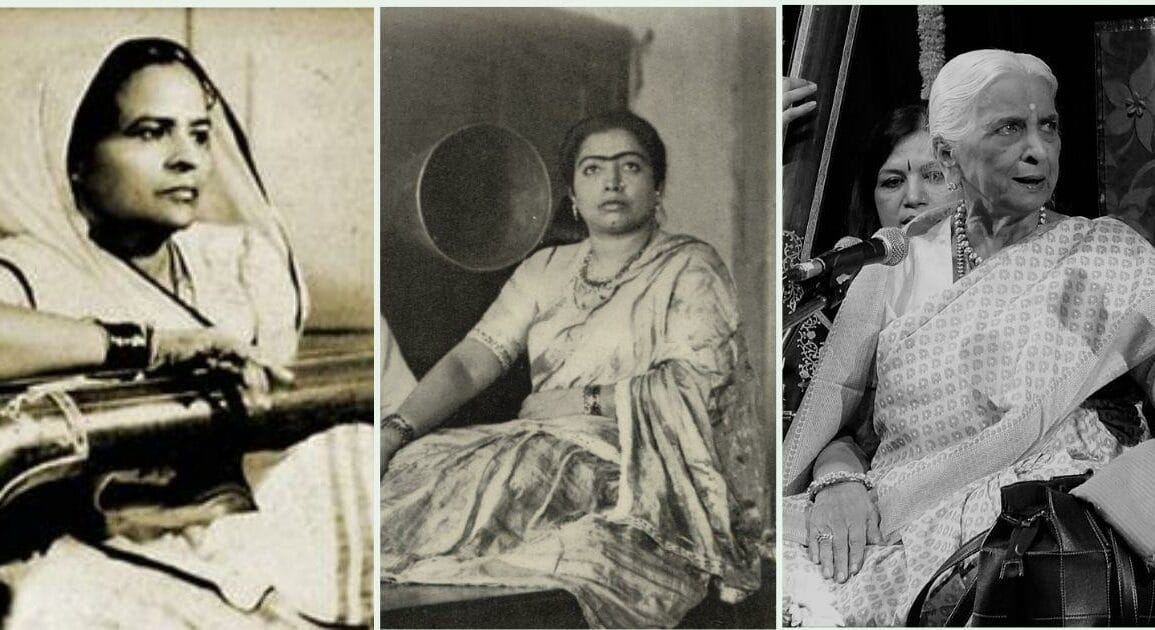

You can hear it at its best in the songs of the grande dames of the thumri, Siddheshwari Devi and Rasoolan Bai. The conclusion of a thumri is marked by a peppy rhythm pattern called the laggi, which makes even the most disinterested of listeners sit up.

Phool gendwa, Rasoolan Bai

The thumri may have had proto forms before the 19th century too, but it is in the Awadh court, especially of Wajid Ali Shah, that it bloomed. It was then a dance song and was sung by the dancer herself/himself for the form that came to be called kathak in the 1930s.

From this courtesan lineage emerged a bevy of women artistes like Gauhar Jaan, Janki Bai and Rasoolan Bai who ruled the arts scene in the late 19th and early 20th century. Begum Akhtar too was nurtured from an early age to become a courtesan performer. However, this ecosystem was effaced by the 1920s by the anti-nautch movement, the collapse of the feudal order and the rise of an urban western-educated middle class repelled by what it considered a debauched art.

As the old order died, its arts were “salvaged” and dominated by others. Male dancers and singers became the custodians of an art that middle class women were not allowed to practise. Some of the most renowned and popular thumri singers of these decades were men – Abdul Karim Khan, Barkat Ali Khan, Faiyaz Khan and, of course, Bade Ghulam Ali Khan. Even the thumri-centric kathak became the preserve of male kathakars. It is interesting that the male vocalists did an outstanding job of recreating the thumri’s femininity, pukar and all, without caricaturising it.

Ab tohe jane nahin doongi, Bade Ghulam Ali Khan

Women re-entered the field, this time from middle class homes, around the late 1940s. But this new thumri of the concert hall was a far slower, more alap-centric thing, closer to the khayal, than the dance song it was. Gone too was the obvious coquetry, the tantalising ada and the nakhra. Words that were explicitly sexual were also erased from the repertory, point out scholars Lalita du Perron and Saba Dewan.

Perron finds that “Bala jobana jina chuvo” (don’t touch my youth/breasts) was changed to “Mori bahiya nahi chuvo” (don’t touch my arm) when sung by a married Benarsi thumri musician. In other instances, “Suni sejwa” (empty bed) became “Suni nagariya” (empty town) and raja (king/patron) transformed into Shyam (Krishna). The narrative was that this was a form pegged to bhakti and spiritualism.

Sunanda Sharma, the student of one such musician who started at the actual threshold of this revival, Girija Devi, says her guru was particular about these changes. “She brought more shastriyata (classicism) and gambhirta (gravity) into the thumri, stayed longer on notes and insisted that we bring more depth into the literature by replacing references to raja/maharaja with, say, Shyam,” said Sharma. She recalls a fascinating little ritual her of guru’s when she switched to the thumri from khayal – she would dab her nose with a handkerchief dipped in itr (scent).

“‘This music is about the senses, about all that is mellow and aesthetic. Treat it so, with respect for sahitya and syntax,’” Sharma recalled her saying.

The coming decades yielded some outstanding thumri singers – Shobha Gurtu, Sarla Bhide, Purnima Chowdhury, Naina Devi and Shubha Mudgal, among these. The thumri has also become a staple in the concert repertoire of khayal singers, although, as cynics point out, as a sort of “light” ending to an evening of high art.

Manoon manoon na, Sarla Bhide

New feminist thinking posits that the thumri dance was a currency that empowered the professional, hereditary artistes to be career women, allowing them to run huge establishments and maintain independence of the kind otherwise denied to women. All the while, it kept alive an art and tradition with creativity and calculation, since all the suggestive singing and signalling were meant to ensure a steady “market”. The erasure of those artistes’ role from music history and the appropriation of their art without fair credit has been critiqued in recent years.

Rao, who refuses to be pinned down to the binaries of the argument around thumri (spiritual/erotic), argues that the form is subversive. “It was open about physicality, not just love or sexuality,” she said. “Fear, hunger, pain, why would these not be a part of our music? These feelings have to be treated with great respect. They are as sacred as anything else in art.”

Du Perron was among the first to counter this narrative. In 2002, she argued in Thumri: A Discussion On The Female Voice of Hindustani Musicthat the idea of the empowering thumri is built on a thin foundation of gender prejudices and misconceptions: because it is emotional, allows grammatical licence, is accessible and has folk origins, it is assigned to femininity. The fact that this music is narrated, performed and created by women does not take away from the fact that “the woman’s experience is constructed by an overarching patriarchal ideology”, she points out. All references to the nayika’s despair, anger and fury in a song like Phool gendwa na maro and so on are eventually indicative of latent desire, a strategy to excite the male clientele.

Saanchi kaho more raja, Purnima Chowdhury

How does the modern vocalist negotiate this tricky terrain? Ethnomusicologist Chloe Alaghband-Zadeh, in her PhD thesis, talks of how vocalist Ashwini Bhide Deshpande picks Tum Radhe Bano Shyam as her favourite. It tells Radha to take control (be the man), a theme that helps the singer negotiate two sticking points in thumri – “both the disreputable, sensuous femininity of the courtesan and the disempowered femininity of ṭhumrī’s conventional love-sick heroines, each problematic for different reasons for a modern-day female performer”.

There is more interesting work in the offing: du Perron is working on the elements of “eve teasing” that may have made poetic sense in the days when women were in purdah but are totally out of time with the world they now inhabit.

We have clearly not heard the last on the thumri and the many ways it can be interpreted with the feminist lens.

Malini Nair is a writer and senior editor based in New Delhi. She is a Kalpalata Fellow for Classical Music Writings for 2021.

This article first appeared on Scroll.in.