Is the “Moonlight Sonata” Really About Moonlight?

Despite its evocative nickname, Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata” has little to do with moonlight. This article explores the true origins, structure, and interpretations of the work, separating poetic myth from musical reality.

Few pieces of classical music are as universally recognised—or as misunderstood—as Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 14 in C-sharp minor, Op. 27, No. 2. Commonly referred to as the “Moonlight Sonata,” the work has, over the centuries, acquired a veil of mystery and romantic melancholy that seems to hang over it like a fog over a midnight lake. But is this really what Beethoven intended? Or has posterity overlaid the piece with layers of poetic sentiment that cloud its original meaning?

Let us dig into the origins, structure, and interpretations of this famous sonata and uncover whether it truly deserves its lunar nickname.

A Name Beethoven Never Heard

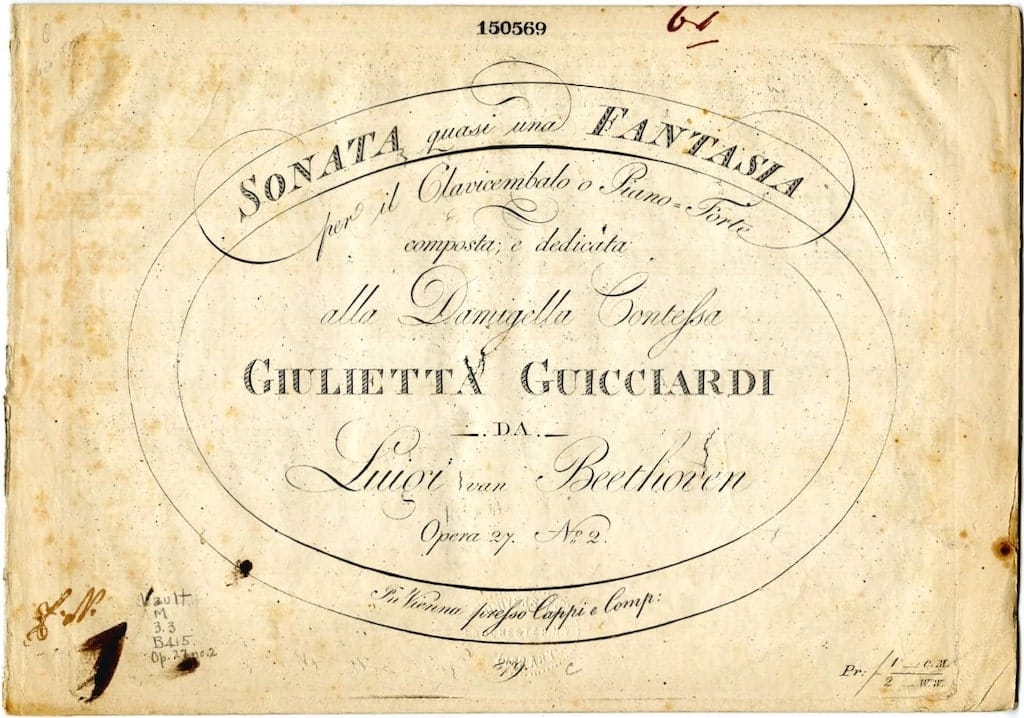

The title “Moonlight Sonata” was not given by Beethoven himself. In fact, the composer titled it Sonata quasi una fantasia—literally, “sonata in the manner of a fantasy”—a subtle but important clue that he was already experimenting with form, mood, and structure, diverging from the strict sonata form typical of the time.

The evocative moniker we know today was coined several years after Beethoven’s death by the German poet and music critic Ludwig Rellstab. In 1832, Rellstab likened the first movement’s dreamy arpeggios to the reflection of moonlight on Lake Lucerne. The phrase caught on, and publishers quickly capitalised on its popularity.

However, there is no historical evidence that Beethoven associated this work with moonlight. On the contrary, the sonata’s brooding tone, unconventional structure, and emotional depth suggest something far more turbulent.

A Work of Mourning and Defiance?

The sonata was composed in 1801 and dedicated to Countess Giulietta Guicciardi, a young aristocrat and one of Beethoven’s pupils. The precise nature of their relationship remains speculative, though Beethoven’s unrequited love for Giulietta is well documented. Some scholars have therefore viewed the piece as a kind of lament—a musical love letter from a tormented soul.

Others point to Beethoven’s increasing awareness of his encroaching deafness during this period, suggesting the music captures his inner desolation and mounting frustration.

Still, any attempt to pin down a specific “meaning” may miss the point. Beethoven often resisted programmatic interpretations of his work. He believed that music expressed the inexpressible—a realm beyond words, images, and, yes, moonlight.

Analysing the Structure

To better understand the work, it helps to explore its three movements and how they interact as a whole.

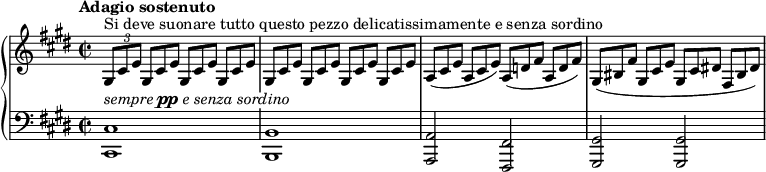

I. Adagio sostenuto

The first movement opens with a slow, hypnotic triplet rhythm over a sparse melody. There is no clear harmonic resolution. The movement meanders with a dreamlike inevitability, avoiding the usual development sections expected in a Classical-era sonata.

This meditative, almost dirge-like mood is likely what inspired Rellstab’s moonlight comparison. But others have heard something closer to a funeral march or a solemn prayer. Composer Hector Berlioz described it as a “lamentation,” while Franz Liszt called it “a dark, ghostly murmur.” Even Carl Czerny, Beethoven’s student, compared it to “a night scene, in which a mournful ghostly voice sounds from the distance.”

The truth may lie somewhere between these visions: a movement of quiet anguish, internalised sorrow, and introspection, not serene moonlight.

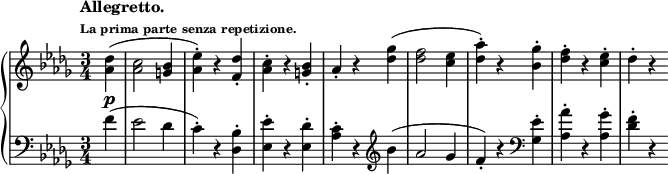

II. Allegretto

The second movement offers brief respite. A gentle dance in D-flat major (the enharmonic equivalent of C-sharp major), it serves as a kind of interlude between the stormy outer movements.

This minuet and trio is graceful but not frivolous. Its understated elegance is deceptive—what Robert Schumann called “a flower between two abysses.” It provides balance and contrast but remains emotionally tethered to the work’s overall mood of ambiguity and restraint.

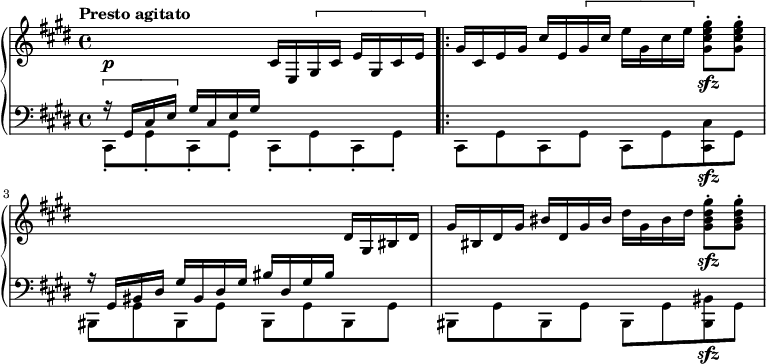

III. Presto agitato

If the first movement is all tension and the second a pause, the third is an eruption. It is rare to find a piano sonata in Beethoven’s time where the final movement is the most intense—and this one blazes with fury.

Marked Presto agitato, it is full of tremolos, rapid arpeggios, and dramatic leaps, demanding tremendous control from the performer. Beethoven here unleashes the storm that simmered beneath the surface all along. It is more appropriate to speak of thunder than moonlight.

This movement is not a resolution but an outburst. It has been interpreted variously as a cry of despair, a fit of rage, or even a vision of fate itself. It closes the sonata not with clarity, but with confrontation.

Romantic Reimaginings

The 19th century was a period of intense romanticisation of Beethoven. As composers and critics sought to canonise him as a visionary genius, his works were often interpreted through an emotional lens. The “Moonlight” epithet suited this narrative perfectly—an enigmatic piece dedicated to a lost love, written in the shadows of impending deafness.

Romantic-era pianists embraced the nickname, and by the time of Franz Liszt and Clara Schumann, the title was already firmly entrenched. It has remained ever since, appearing on concert programmes, album covers, and beginner piano anthologies worldwide.

And yet, while the name has helped popularise the piece, it also risks narrowing its emotional range. Listeners expecting nocturnal serenity may overlook the turmoil and tension at its heart.

Reframing Our Listening

If we are to do justice to Beethoven’s vision, we must learn to hear this work not through the lens of Rellstab’s moonlit poetry, but on its own terms. That means embracing its contradictions: the first movement’s quiet but unrelieved tension, the second’s brief smile, and the third’s unleashed fury.

It is a work that anticipates Romanticism, yes, but also challenges its sentimental excesses. Beethoven subverts classical expectations: the “fantasia-like” designation in the title suggests freedom from formal rigidity. The emotional arc is internal, unresolved, and deeply human.

One could argue that the nickname, while inaccurate, has nevertheless contributed to the work’s mystique. It invites people into the piece, even if under slightly false pretences. And perhaps that is not altogether a bad thing.

Moonlight or Not, It Endures

Whether or not Beethoven ever imagined moonlight flickering across a lake as he composed, his sonata has earned its place in the canon of Western music. It straddles the Classical and Romantic eras, breaking form while adhering to expressive discipline. It is both lyrical and violent, inward and explosive.

The “Moonlight Sonata” is not about moonlight. It is about human complexity: longing, loss, defiance, and perhaps even hope. Its enduring popularity rests not in a single image, but in its vast emotional canvas—one that continues to speak to listeners more than two centuries later.

So the next time you hear that famous opening, resist the temptation to picture moonlight on a still lake. Instead, listen to the silence between the notes, the tension in the unresolved chords, and the storm that brews in the distance. That, perhaps, is where the real story lies.