How to Teach Piano Sight Reading Successfully – Part 1

GROWING THE SKILL

So often relegated to the “too difficult” category, feared and loathed as part of the exam syllabus, wistfully envied in the “naturally talented” … sight reading seldom excites optimism or enthusiasm. Yet it would make no sense to ignore it in building the full set of Useful Pianist skills. Being asked to play accompaniments, wanting to get a quick idea of a piece, exploring new styles, having little time to do any of this: all point to the need for developing adequate sight reading.

I have good news on this. To give you a bit of context, I have always personally been a poor sight reader, compared to my level of repertoire, and as I went up through the grades in my school years my sight reading failed to keep up. At music college I found sight reading classes both embarrassing and depressing, as everybody else seemed so much better and there appeared to be no remedy for me.

So what is the good news? Well, now I know from my own experience and efforts in both teaching and playing that it is possible to become a useful sight reader, and I know how – because I’ve been working on this, and thinking hard about it, for a very long time.

Since I was a budding piano student there has been enormous growth in the variety and quantity of piano sight reading resources. I think I have a copy of most of them! One common thread through all of them, which I wholeheartedly endorse, is that in order to improve, you have to actually do sight reading all the time. Not just for a few weeks before the next exam, not if-and-when you remember, but as often as you play the piano at all. This is the biggest lever of success and if you don’t have time to read the rest of this article, just do that with all your students and there will be progress!

THE BARRIER(S)

There is no one single reason for poor sight reading, and it can show different symptoms. I would summarise from my own teaching experience that the main problems are:

- Unwillingness to use notation generally (preference for rote learning)

- Reading the bass clef

- Finding the notes (especially changing hand position)

- Recognising and reproducing common patterns

- Playing the correct black notes

- Reading chords

- Managing unfamiliar rhythms

- Keeping going (staying in time)

- Processing two staves of music into two simultaneous sets of finger movements

- General lack of keyboard confidence

Some of these are slow growing problems that are masked by the coaching that comes in lessons. Under the very respectable guise of “teaching the sound before the symbol” it is possible for students to ignore the detail of the printed copy and rely mostly on what they have rote learned in the lesson. It becomes more a case of “remembering sounds/movements and occasionally relating them to some of the symbols”. This arguably works OK for technical exercises and the intensive study of repertoire but is a serious barrier to progress in sight reading.

By the way, I am not suggesting that everybody should slog away at notation just for the sake of it. Our topmost aim at all times is to make music and enjoy doing so; but so many people feel inadequate about their sight reading, and it is such a commonly expected skill among those who wish to avail themselves of a useful pianist, that it is at least worth encouraging your students to treat it as a good aspiration – or to make peace with the idea that fluent notation management is (intentionally) not going to be part of their musicianship.

FIRST STEPS, AND THE SLIPPERY SLOPE

If you are teaching a young beginner, almost every lesson will include sight reading quite naturally because they are learning how to read notation at practically the same rate that they are learning new little songs.

As learners work through their tutor books, we are left in the hands of the authors as to how much sight reading is purposefully developed. Matching supplements such as flash cards and theory/musicianship books can help, but not all publishers provide these. If you are teaching sensitively according to each student’s strengths and preferences, you will be working hard to use that weekly half hour for motivation, reinforcement, correction, planning and exploring already. I am certainly guilty at times of letting sight reading fall off the end of the lesson, with a note to “keep this up” being all they take home.

Then we have the common situation of older students (especially adults) and non-beginners who, for whatever reason, arrive at your teaching studio needing help with sight reading and aware it’s a problem. The first thing is to reassure them that they are not alone! Most will know and envy somebody who is a really good sight reader. This is the first barrier we must break down. People naturally don’t like doing things they don’t feel good at, and adults get rapidly frustrated and can give it up as a lost cause. This is a pity, as (like other worthwhile long term projects) persistence over time will bring rewards. However, since everybody likes novelty and a quick fix, I work on three strands of practising rather than insisting on only the slowest and surest.

THE REMEDIES

1 Do sight reading every day

2 Develop three parallel strands of practice :

- a – Working steadily up from a level that is easy

- b – Quick studies

- c – Strategies for tough challenges

The first should need no further elaboration! Getting your students to commit to this and stick with it will be the task.

The second group covers so much that there will not be room for all of it in this article. I will come back to (c) in part 2.

THE LONG PROJECT (A)

Eventually we are aiming to bring the level of sight reading gradually and solidly up from where it really is, to somewhere more useful. This may mean an initial assessment, which you can easily carry out using specimen sight reading exam tests. Please do keep it light and unthreatening! Start at grade 1 with everybody and stop as soon as they are unable to play comfortably well. Try a key signature or two, and you will quickly be able to see whether they notice and accommodate it or not. For many people, their comfort zone in piano sight reading barely includes two staves, let alone playing hands together. There must be a cheerful air of acceptance around this, and a willingness to take the first steps in a safe place.

Grade labels are not very helpful when you start this, since somebody who has passed grade 5 will not like the news that their true sight reading level is around grade 2. Soften the blow by talking about how all their other progress up the grades has been long term and gradual, and this is no different: with adults you can also openly discuss the psychological self-care needed to break down barriers. Banish all negative statements and keep the focus on the real progress that is attainable. It’s not as bad as trying to keep those New Year gym and diet resolutions! All the student has to do is make sight reading a part of their daily piano warm-up, and your responsibility as teacher is to ensure that they never run out of material to sight read. This may mean a lot of lending of books! If they have easy music at home, they are welcome to use it, but get them to bring it to the lesson for you to check suitability.

SIGHT READING INNOVATIONS

I occasionally use iPad sight reading apps (there are quite a few out there now) which normally scroll away or delete bars as the student plays. Some apps can “hear” what is played, whilst others just put up the music. I think these can be useful at any level, but I don’t have the space here to investigate the full range, especially as information about apps can become dated very quickly, or local markets may have other options. I would encourage you to explore them and find out what works for you and your students.

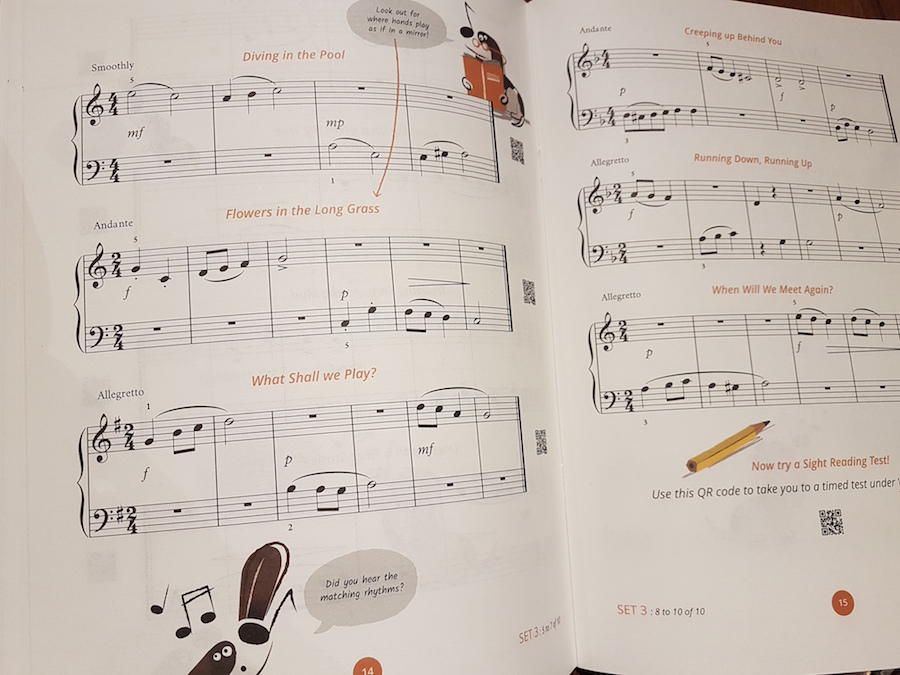

One innovation I should certainly mention, though, is the excellent new series of books, Learn to Sight Read: Piano published by E-MusicMaestro, and also available online. This cleverly takes advantage of the fact that every student these days has a smartphone or tablet, and far fewer have a CD player handy. So by adding QR codes next to the sight reading resources, they have made it possible for the player to hear a recording of the example very conveniently. This is really helpful for many students who struggle to “hear it off the page” and therefore don’t really know whether they are playing the right notes. One of the most-repeated complaint/excuses I hear from students about notation reading in general is, “It’s difficult when I don’t know what it sounds like” – which is one of the reasons we get so many requests from them to learn pop songs and so on. This new resource will really help to reinforce notation reading because they will not only see and feel patterns, they will learn to hear them (at first perhaps in outline, but with improving accuracy as they get more familiar). The authors have also included rhythm recognition, with a witty twist, by making the title of each piece fit the rhythm of its opening. All of these new features make it fun for both teacher and pupil to explore music at sight in lessons whilst providing lots of support at home, which is where all the improvement is really going to be achieved. Anything that makes it more fun, easier and more productive to sight read at home has to be worth a look!

Ideally, when playing at their correct level, every attempt should be successful, at least second if not first time round. As they begin to move into new challenges – black notes, hands together, chords, position changes, tricky rhythms – make sure that you and they are aware of what is new and give it space to grow. Mostly this will require playing more slowly, and not skimming past the new problem but really addressing it. If this long term sight reading project is adopted as a three-minutes-a-day habit, it will be gratifying to look back three or four times a year and see how the slow progress builds the bigger picture.

TWO STAVES AT ONCE

I suspect this is the biggest difference between sight reading on a keyboard and sight reading on any other instrument. (Guitarists and harpists may wish to disagree). Most other players only have to produce one note at a time, and even if there are more (such as double stopped violin notes) they are all on one stave; but pianists routinely have to process two parallel lines of music, often with extra notes stacked into chord shapes. This is not a trivial demand on the brain’s processing power.

For anybody who first plays a melody instrument (violin, clarinet, trumpet, recorder, flute etc) the treble clef will have been fairly well learned by the time they try piano. Even first-study pianists can struggle with the bass clef for various reasons, including the fact that it really is quite confusing. As far back as 1702, M. de Saint Lambert was advocating its abolition in keyboard music, and proposed a simpler-to-read replacement, but the weight of theory and existing norms seems to have overpowered his efforts. So we are stuck with it, and if remedial work is needed then we must tackle it. Maisie Aldridge has helpfully written “The Bass Clef Book” for this very purpose, and I have used it plenty of times to get people over their initial issues. It is not compatible with most beginner books because it starts with bottom line G, but for those who should know better by now, it is helpful, not least because it often uses well-known tunes.

THE HALFWAY HOUSE (B)

There is a component of some diploma exams called “Quick Study” which I wish the examining boards would introduce in earlier grades, perhaps as an alternative to sight reading. I don’t think I have ever, except in an exam, had to perform at sight a complete solo piece at thirty seconds’ notice. The Quick Study is much closer to the real life Useful Pianist situation in which somebody gives you music to play at rather short notice but with maybe a day or two to practise. For this you need to get a sense of what is instantly possible, what is not worth attempting (and how to cover that up) and what can be done with a few minutes’ concentrated practice. In effect, it is halfway between learning and sight reading, without any real chance to polish.

There is great advantage and enjoyment to be gained from giving students a weekly assignment of an easy new piece to play at the next lesson. An occasional (or frequent) duet part would be even better, so that you can develop their ability to keep going along with another player, as in any accompaniment scenario. It also helps them to understand how much fun it is to explore lots of repertoire without commitment and pressure, and their musical and stylistic knowledge can broaden as they go, with little effort. Keep it varied and always inside the comfort zone (because we want all this to boost confidence).

ONE NOTE ABOUT DUETS

Look carefully at what you are using and make sure their left hand part is in the bass clef. Many beginner and elementary level duet books have a “teacher plays Secondo” approach with an easy Primo part, for the student, that is given at pitch in the treble clef for both hands. You need to find and use the collections that keep the Primo LH in the bass clef and make the student play an octave higher. It is much easier just to move the bench along and pretend a different C is middle C, and far less confusing for those who have just painstakingly mastered associating the LH fourth space with a G. Furthermore, sight reading both hands in the treble clef does not help with progress towards eventual “real” accompaniments, which we can only start using once sight reading is fairly well advanced – I don’t know of any chamber music in which there is a genuinely easy piano part!

In my next article, I will continue the sight reading topic and show you and your students how to conquer the panic when the going gets tough.

By Janet Noakes. This article first appeared on E-Music Maestro.