How Music Education Can Create a Better World

The science behind the advantages of early music education is rock solid. These feature films and documentaries, that introduced us to powerful stories from around the world, reinforce what we already know to be true— that music can heal in more ways than one.

This year, the Academy Award for the Best Documentary Short Film was awarded to The Last Repair Shop. It is a heart-warming film that profiles four individuals from among a handful of luthiers, repairers and restorers of musical instruments at a warehouse in Los Angeles, one of the few American cities to still offer and fix musical instruments for its public-school students at no cost. Each of those profiled specialises in an orchestra section or piano repair. The film also focuses on some of the students touched by the repair shop’s work.

Accepting the award, director, producer and music composer Kris Bowers made an important point: “Music education isn’t just about creating amazing musicians; it’s about creating amazing humans.”

What I found particularly touching in the stories of each of the specialists and the students, and their journeys towards music in general or instrument repair in particular, was the common thread of poverty and how music helped them find a path to self-esteem and a better life.

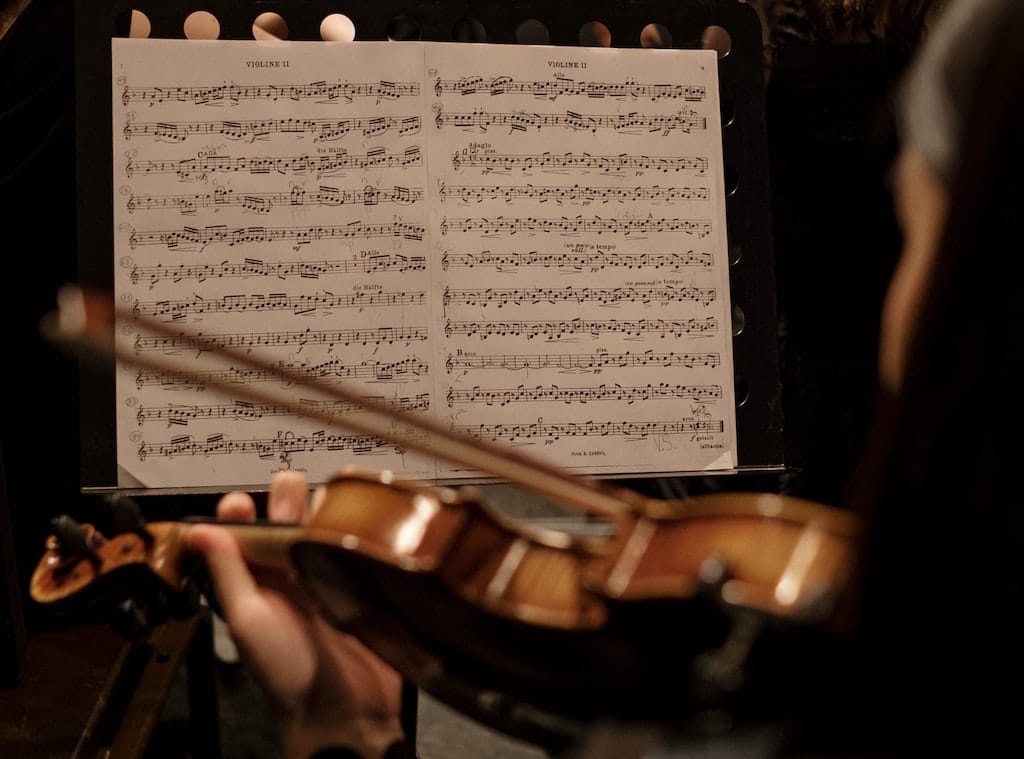

As founder and project director of Child’s Play India Foundation, a music education charity working with disadvantaged children, I know from personal experience the various issues surrounding appropriately sized instruments, the difficulties in procuring, maintaining and repairing them. Many beginner instruments (tiny violins, violas, cellos) are not only hard to come by, but often not of requisite quality. This can be off-putting to a small child (and their parents), especially if the sound is not pleasing. What comes across in The Last Repair Shop is that such highly skilled instrument maintenance and repair, when offered gratis, is a labour of love.

However, it takes not just love but dogged perseverance to provide music education. This is the underlying thread in all the films and documentaries that have highlighted music education.

Mr. Holland’s Opus (1995) was a memorable film with Richard Dreyfuss in the title role of Glenn Holland, a dedicated high school music teacher who attempts to compose his own music while struggling to balance his job and life with his wife and profoundly deaf son. All through the film, Holland considers himself a failure and must constantly battle bureaucracy to sustain funding for music education in his school and state. But even though he loses that fight and is eventually made redundant, the students he taught over the decades surprise him by playing the composition he has been working on all his life. All of them collectively are his magnum opus. They have been touched by his kindness, generosity of spirit and the sense of self-worth he instilled in them by never giving up on them. A tear-jerking finale if ever there was one.

Music of the Heart (1999) is a dramatisation of the true story of Roberta Guaspari, portrayed by Meryl Streep, who founded the Opus 118 Harlem School of Music and fought for music education funding in New York City public schools. The film was inspired by the 1995 documentary, Small Wonders, which was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.

In Music of the Heart, Guaspari is attempting to rebuild her life with her two sons after a divorce. She accepts a substitute violin teaching position at a rough inner-city school, in New York’s East Harlem area, then rife with poverty and crime. The film shows how, armed with toughness and determination, she inspires a group of children and wins over their initially sceptical parents. The music programme slowly develops and attracts publicity, eventually expanding to neighbouring areas. The climax is a fundraising concert at Carnegie Hall to save the programme as state funding has been withdrawn. It features Guaspari’s past and present students and a host of celebrity violinists who actually played in the real-life concert. They appear in the film as themselves: Itzhak Perlman, Arnold Steinhardt (first violinist of the Guarneri string quartet), Isaac Stern, Diane Monroe and Joshua Bell.

One review by Steven Rosen in The Denver Post summed up my own feeling about the film: “…the key to Meryl Streep’s fine performance is that she makes Guaspari unheroically ordinary. Ultimately that makes her even more extraordinary.”

Tocar y luchar or To Play and to Fight (2006) is a documentary film about El Sistema (which translates to The System), a publicly financed music education programme founded in Venezuela in 1975 by educator, musician and activist José Antonio Abreu. El Sistemainspired programmes provide what International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies describes as “free classical music education that promotes human opportunity and development for impoverished children.” They now run in more than 60 other countries including India, where this writer’s own foundation takes its inspiration from it.

The film won several awards, including Best Documentary at two international film festivals. It catapulted El Sistema’s work to international fame, spawning music education initiatives far and wide. Sistemang Pilipino, a non-profit organisation dedicated to providing music education to Filipino children and youth, began in spirit in October 2009, when the documentary was shown to a group of violin teachers. The film underscores how music education can become a social movement, a force for empowerment and greater good. The documentary includes interviews with luminaries from the world of classical music, including tenor Plácido Domingo and conductors Claudio Abbado and Simon Rattle.

Kinshasa Symphony (2010) is a German documentary film set in the capital of a country that is today in crisis, the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The film tells the incredible story of how Armand Diangienda, after losing his job as an airline pilot, became founder and conductor of the Orchestre Symphonique Kimbanguiste (OSK) in 1994. At its inception, the ensemble had only 12 amateur musicians that shared instruments. It would grow to about 200 amateur musicians and performers consisting of a full orchestra and choir. For many years, the OSK was the only symphony orchestra known to reside in Central Africa, and the world’s only all-black orchestra.

Landfill Harmonic (2015) is a documentary film about music teacher Favio Chavez and his Recycled Orchestra of Cateura, a children’s orchestra in Paraguay which performs with materials recycled and assembled from a trash landfill near Asunción, the capital city. The orchestra originated in the Sonidos de la Tierra project created and directed by Luis Szarán since 2002. In a review, The New York Times wrote, “an inspiring tale— if it were fiction you’d dismiss it as unbelievable.”

Szarán makes a similar point to that made by Bowers recently at the Oscars, when he says in the film: “Our main goal isn’t [just] to form good musicians, but to form good citizens.” He continues, using the classic metaphor for social empowerment: “We haven’t given them fish—as they say—but taught them how to fish.”

The evidence that music education shapes more empathic humans and “significantly contributes to society by fostering cultural appreciation, promoting social inclusion and diversity, and offering a meaningful means of expression and communication for individuals of all ages” as Lisbon-based musicologist Roberto Votta puts it, is quite solid. Despite this, one sees in all the films from different parts of the world that music education is largely woefully underfunded. Hopefully, this Academy Award win for The Last Repair Shop will reiterate the value of music education to policy shapers across the world.

By Luis Dias. This piece was originally published by the National Centre for the Performing Arts, Mumbai, in the May 2024 issue of ON Stage – their monthly arts magazine.