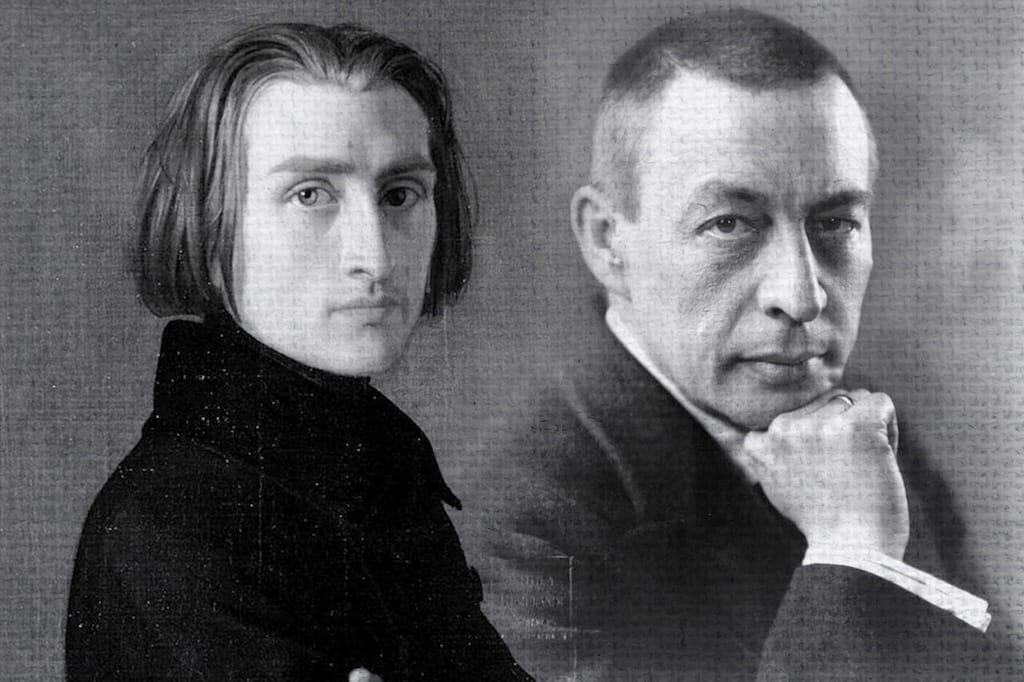

How Liszt and Rachmaninoff Stunned Audiences

Franz Liszt and Sergei Rachmaninoff redefined piano performance. Blending superhuman technique with emotional depth, they turned concerts into unforgettable experiences and forged the very ideal of the modern virtuoso pianist.

Few names in the history of piano playing command the same reverence as Franz Liszt and Sergei Rachmaninoff. Both were towering figures—literally and metaphorically—whose performances transcended mere musicianship. They embodied the very idea of the virtuoso, dazzling audiences with technical mastery, emotional depth, and magnetic presence.

Though separated by nearly a century, Liszt and Rachmaninoff shared more than prodigious talent. They revolutionised what it meant to be a pianist, transforming the instrument into an orchestra under ten fingers and elevating concert performance to high art. Their legacies shaped the course of piano playing—and the very psychology of musical stardom.

The Birth of the Modern Virtuoso

Before Liszt, the pianist was primarily a composer-performer, seated modestly at the keyboard. Concerts were often intimate affairs, held in aristocratic salons rather than grand halls. Liszt changed that forever.

Born in 1811 in Hungary, Franz Liszt combined prodigious technique with theatrical flair. By his twenties, he was touring Europe, setting the continent ablaze with his performances. Women reportedly fainted during his concerts, admirers collected his discarded gloves and locks of hair, and newspapers coined the term Lisztomania to describe the hysteria surrounding him.

Liszt’s performances were revolutionary not only in showmanship but in their physicality. He turned the piano sideways on stage—a practice now standard—so audiences could see his profile and expressive gestures. He was among the first pianists to perform entirely from memory, a move that astonished listeners and became the benchmark of professionalism.

Liszt’s technical innovations—rapid octaves, transcendental leaps, intricate arpeggios—pushed the piano to its limits. His Transcendental Études, Hungarian Rhapsodies, and concertos remain among the most demanding works ever written for the instrument. Yet Liszt’s genius was not mere bravura. Beneath the fireworks lay profound musical understanding and poetic imagination.

He often spoke of the piano as a “sounding orchestra,” and his works reveal that orchestral sensibility: rich textures, shifting colours, and a sense of vast spatial resonance. Liszt turned piano recitals into spiritual experiences, elevating virtuosity into a form of expression rather than mere display.

The Legend of Lisztomania

The phenomenon of Lisztomania deserves special mention—it was, in essence, the first instance of modern celebrity culture. Audiences thronged to his performances in unprecedented numbers. Eyewitnesses described women fighting over his handkerchiefs, fainting in ecstasy, and rushing the stage after concerts.

Liszt himself was bemused but strategic. He cultivated an image of the romantic hero—dark hair, piercing gaze, flowing coats—while maintaining an almost saintly devotion to his art. He travelled with his own piano, assistant, and entourage, performing hundreds of concerts a year across Europe.

In today’s terms, Liszt was both the rock star and influencer of his age. Yet his fame rested on substance. His recitals were meticulously structured, featuring not only his own dazzling compositions but transcriptions of Beethoven symphonies and Schubert songs—acts of advocacy that brought the music of others to wider audiences.

By the time he retired from the concert stage at 35, Liszt had redefined the role of the pianist from accompanist to solo artist—a transformation that would shape the concert tradition for centuries.

Rachmaninoff: The Romantic Giant

When Sergei Rachmaninoff emerged at the turn of the 20th century, the cult of the virtuoso was already well established. Yet he brought something different: a fusion of colossal power and profound melancholy.

Born in Russia in 1873, Rachmaninoff was a composer, conductor, and one of the last great representatives of Romanticism. His hands were famously enormous—he could span a twelfth on the keyboard—allowing him to execute massive chords and sweeping textures that others could only approximate.

Unlike Liszt’s flamboyant stage persona, Rachmaninoff was reserved, almost austere. Tall, sombre, and introspective, he let the music speak for him. Yet his performances were legendary for their emotional intensity and technical perfection. Audiences described being overwhelmed by the sheer sonic power he produced—tones of clarity and depth that made the piano sing like a human voice.

His interpretations of Chopin, Schumann, and particularly his own works were said to possess a hypnotic quality. He performed with unerring control, never seeming to strain, his hands gliding effortlessly over the keys.

Rachmaninoff’s own compositions—such as the Piano Concertos Nos. 2 and 3, the Études-Tableaux, and Prelude in C-sharp minor—became touchstones of Romantic pianism. They fused grand architecture with emotional vulnerability, demanding both Herculean stamina and lyrical sensitivity.

Triumph Over Adversity

Behind Rachmaninoff’s stoic exterior lay a man shaped by profound struggles. After the catastrophic failure of his First Symphony in 1897, he suffered a deep depression that nearly ended his career. Only after months of therapy with Dr. Nikolai Dahl, a pioneer of hypnotherapy, did Rachmaninoff regain confidence and compose his Second Piano Concerto, dedicated to Dahl in gratitude.

That concerto became one of the most beloved works in the repertoire—lush, romantic, and cathartic. Its success marked Rachmaninoff’s rebirth as both composer and performer, proving that vulnerability could coexist with virtuosity.

When political turmoil forced him to leave Russia in 1917, Rachmaninoff rebuilt his life in exile, performing across Europe and America. Though he often longed for home, his concerts became legendary events, drawing crowds as immense as Liszt’s a century earlier.

Virtuosity with a Soul

Both Liszt and Rachmaninoff faced critics who accused them of excessive virtuosity—of dazzling technique at the expense of depth. Yet time has proven such charges unfounded. Their artistry demonstrates that virtuosity and expressiveness are not opposites but partners.

Liszt’s late works, such as Nuages gris and La lugubre gondola, anticipate Impressionism and modernism, revealing a stark, introspective side far removed from his earlier bravura. Rachmaninoff’s music, too, often mingles grandeur with fragility, power with nostalgia.

They understood that virtuosity was not about speed or volume—it was about command: the ability to shape every nuance, every phrase, every silence. Both men transformed the piano into a vessel for emotion, intellect, and even spirituality.

The Pianist as Composer

Another link between Liszt and Rachmaninoff is their dual identity as composers. Unlike modern pianists who focus solely on interpretation, they wrote much of the music they performed. This allowed them to tailor works to their unique strengths, pushing the instrument’s possibilities further each time.

Liszt’s innovations in harmony, thematic transformation, and texture paved the way for Wagner, Debussy, and even Ravel. Rachmaninoff, meanwhile, carried the Romantic idiom into the 20th century, bridging Chopin’s lyricism with modern pianistic complexity. Their works remain both technical milestones and emotional testaments—pieces every serious pianist aspires to master, not merely play.