How a music form inspired by the songs of camel drivers of Punjab-Sindh became popular in Bengal

The word wild pops up often in colonial descriptions of the tappa, a dazzlingly fast-paced, quirky music form that revels in the art of the unpredictable. “Wild but pleasing when understood,” says 18th-century music collector William Hamilton Bird in Oriental Miscellany (1789). Says Sarah Plowden, another 18th-century chronicler of Hindustani music, “A sort of wild, harsh music without any air.”

How the tappa travelled east, transformed into the toppa, and became a widespread part of popular music in Bengal is a fascinating story of cultural and social shifts spanning over four centuries.

As the name suggests, the northern tappa, believed to have been inspired by the songs of the camel drivers of Punjab-Sindh, literally trips and skitters over notes, words and beats, but with the singer in absolute control of the creative rein.

“The play of notes, phrases and the use of aada taal [off-beat rhythm patterns] in the tappa requires an altogether different kind of vocal training and arduous breath control, which explains its rare appearance at concerts,” said Shashwati Mandal, among the exponents of the form from the Gwalior gharana.

Despite this, the tappa is often referred to as a “semi” or “light” classical because it is at variance with the meditative style of the khayal. A 1910/1911 recording of a tappa in raga Kafi by British musicologist AH Fox Strangways describes it as “light classical Hindustani vocal composition”.

“Believe me there is nothing light about the tappa; the range of harkats (pacy embellishments) it employs – it is highly complicated,” said veteran khayal singer Shanno Khurana, 95, the oldest living exponent of the form. “I used to hear the legendary Rasoolan Bai, Siddheshwari Devi and Badi Moti Bai sing the tappa and marvel at their masterly control of the music.”

The other formidable tappa singer of our times is Malini Rajurkar of Gwalior gharana, which, along with Benares, is the citadel of the tappa.

When it reached Bengal, the tappa’s frenzy was tempered down, putting poetry and bhav – and not dynamic vocalism – centre stage. Over decades, the form’s idiosyncrasies were plucked out and integrated into an array of music forms – devotionals, folk and patriotic songs, jatra (theatre), popular songs and so forth.

Love and separation

A woman’s anxiety at separation from her loved one and the plea to be united are usually the themes of a tappa, set mostly in two-four-lines. As is the case in this Kafi classic by Rajurkar.

O miyan jaanewale, tainu Allahdi kasam, phir aare nainon wale/Aanda jaanda tussi man le janda/Aur sajan gale lag ja, sharshar matvale (O peripatetic one, you have stolen my heart, come back and hold me in an embrace).

But to understand the evolution of the form, it is important to jump back to the 18th century and perhaps even 100 years earlier.

The hereditary musician Ghulam Nabi Shori (1742-’92) was among the khayal geniuses of the 18th century Awadh court of Nawab Asafuddaulah. It is commonly believed that while in search of wider musical experiences, he travelled north where he heard the songs of the camel drivers of the Punjab-Sindh region. Shori then wove this music into existing Hindustani practices to craft the tappa.

Most songs in the contemporary tappa repertoire are attributed to Shori, his name appearing in the last line of two tuks (stanzas).

But in her essay, The Origins and Early Development of Khayal, music historian Katherine Schofield cites multiple 17th-century texts, such as the Mirzanama and the Tuhfat-al-Hind, to establish that the tappa was already current in Delhi 100 years before it became the rage in Lucknow.

What Shori likely did was to provide an Awadh makeover for what British Orientalists William Jones and Augustus Willard describe in Music of India (1834) as the “very rude style” of camel drivers.

“Tappas were sung in multiple languages and dialects of the north and the west of undivided India, such as Punjabi, Sindhi, Multani, Bannochi, Derawali and Saraiki,” said Khurana.

While Bengali tappas are often described as “mishti [sweet], more lyrical”, there is abundant charm in the tappas of the north. A lovely anecdote from Khurana’s life as a young bride in Multan describes this best. A Punjabi-speaker married into a family which spoke Derewali and Saraiki, she found herself struggling to understand conversations.

Summoned to fetch her mother-in-law’s paunkdi (better known in Punjabi as parandi, an ornamental hair extension), she sat down to write her own tappa in raga Kafi in Derewali:

Van shver maindi paunkdi jhin aa / Dekhin dekhin kithai dhain pave na /

Phulaan da phumman, tareyaan da phumman / Dhain pave na

(Go find my parandi / it is strung with flowers and stars / it should never be soiled.)

Tappa travels east

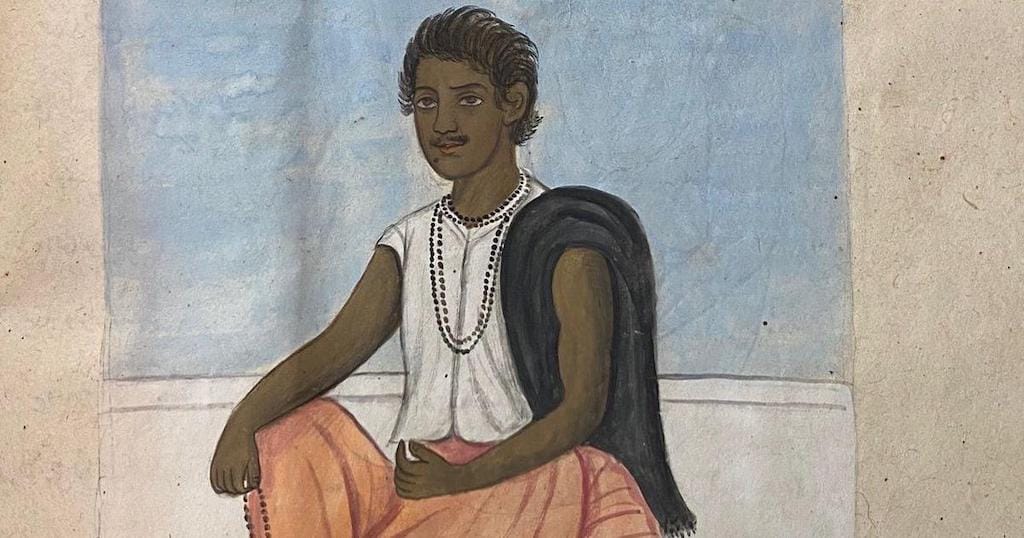

In roughly the same decades of the 18th century when the tappa was becoming fashionable in Lucknow, an educated, upper-class Bengali found himself falling for its quicksilver charms. Ramnidhi Gupta, better known as Nidhu Babu, was born just a year before Shori and went on to live four decades after him.

The pursuit of the elegant arts of the north was quite the mode among the elite men of Bengal at the time and Gupta found himself a Hindustani ustad during his stint in the collectorate at Chhapra in 1776-’94. This was where he likely first encountered the tappa.

Nidhu Babu took the tappa of the north and refashioned it into something typically Bengali. He slowed down its frenetic tempo and wrote up an impressive body of tappas, packed with love and pathos. These compositions, longer than Shori’s brief verses, were later compiled into a volume, the Geet Ratna Granth (1837), to ensure their correct interpretation.

Various accounts say Nidhi Babu’s songs were addressed to the love of his life, one Srimati – described as “concubine of Mahananda Roy, diwan of the Murshidabad collectorate” in scholar Ramakanta Chakrabarty’s 1986 essay Nidhu Babu’s Tappa published in the Journal of the Indian Musicological Society. The story of his tragic passion even made its way into a Bengali film Amar Geeti – starring Soumitra Chatterjee as Nidhu Babu – which featured one of his most popular and melodic compositions: Tumari Tulona Tumi Pran (You Are Incomparable), sung by the best-known exponent of the Nidhu repertoire, Ramkumar Chatterjee.

“He was a pioneer of the kavya gaan [poetry-centric songs] and prem and biraha were the dominant themes, though he did write some work that was patriotic and spiritual in nature,” said Devojit Bandyopadhyay, who has researched extensively on the history of theatre music in Bengal.

Nidhu Babu’s tappas were something of a revolution in a musical landscape ruled by two extremes – classic devotionals and erotic songs, according to Chakrabarty. His compositions found a mid-ground, placing songs of romantic love in the classical framework. Though they never crossed the platonic line, the songs drew flak from purists and conservatives for being “obscene”, as per his biographers.

Interestingly, in his times, Nidhu Babu’s tappas were considered too risqué for women. Critics classed his songs as brothel ditties and women who sang them were castigated as licentious, says scholar Sumit Mukherji in his paper Ramnidhi Gupta and Cultural Humanism in 18th Century Bengal. “Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay portrayed a woman character in his novel Bishbriksha [Poison Tree] as ‘shamelessly’ declaring at a public function that she would listen to Nidhu Babu’s Tappa alone and nothing else,” said Mukerji.

Among the best-loved modern singers of the Gupta repertoire were Kalipada Pathak, Ramkumar Chatterjee and Chandidas Mal. So enthralled was Bengal by the form that other tappa composers entered the music scene. Of them the best known were Sridhar Kathak and Kalidas Chattopadhyay and Kali “Mirza” (he affected the airs of and dressed like an Awadhi grandee).

‘Rabindric’ tappa

Over time, says Chakrabarty, the tappa was assimilated into various song forms of Bengal including folk and theatre. For example, Gopal Ude, a jatra exponent of the 19th century, took it into theatre music, ensuring its spread among the non-elite in rural and small-town Bengal.

In time, the form became frivolous, says Chakrabarty, and fell of its pedestal of high literature and high music. Its next revival was under Tagore, an eclectic thinker and composer.

If in Nidhu Babu’s hands the tappa slowed down, under Tagore’s baton it became anther genre altogether – he wove its characteristics into all kinds of compositions to achieve certain melodic and emotional effect.

Seasoned Rabindra sangeet exponent Pramita Mallick calls them “Rabindric” tappas because they were very distinct from the genre shaped by Shori or even Nidhu Babu – the lyrics were longer, going up to eight lines, and the playful harkats were used to frame the beauty of the poetry, not vice-versa. They are also sung mostly with no percussive support.

“He had learnt and admired Nidhu Babu’s tappas but he had always refused to restrict himself to any one style or one guru,” said Mallick. “Poetry was primary in his songs and he would use whatever style or a mix of styles he needed to bring out a certain mood. So it went into patriotic songs, dhrupads, spiritual compositions, seasonal [ritu] songs; sometimes he would bring in just one or two phrases with typical tappa structures.”

One of the oft-cited uses of a Tagore tappa to create a certain mood was in the Satyajit Ray film Kanchenjunga, in which E Porobash Robe Ke (Who Will live in this Alien Land) was used to paint a middle-aged woman’s isolation.

From the dusty camel trails of Punjab and Sindh to the courts of Awadh, Gwalior and Benares and finally to Bengal’s music traditions, there was one thing all tappa forms did – pack a punch.

Malini Nair is a writer and senior editor based in New Delhi. She is a Kalpalata Fellow for Classical Music Writings for 2022.

This article first appeared on Scroll.in.