Holst’s “The Planets”: Seven Astrological Mood Pictures

Take a moment and consider the most evocative excerpts from John Williams’ Star Wars film scores, the hypnotic, meditative tones of electronic ambient music, and the late twentieth century pop song’s formulaic concluding “fade out.”

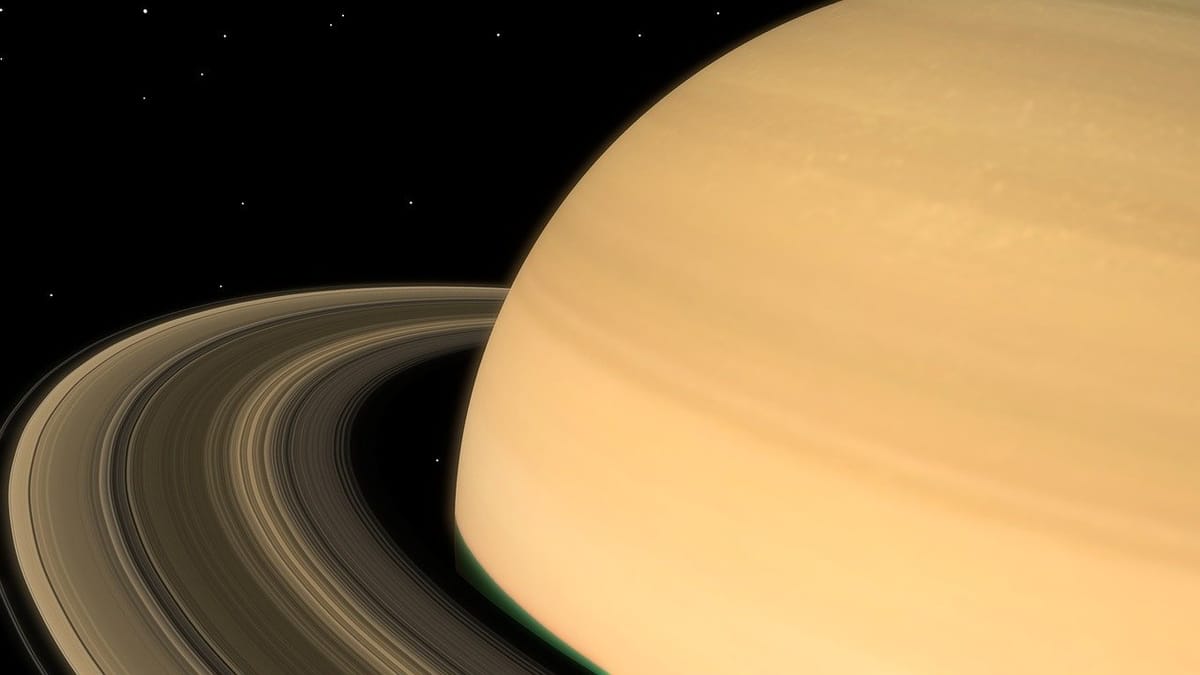

It could be argued that all were vaguely anticipated by Gustav Holst’s seven-movement orchestral suite, The Planets, composed between 1914 and 1917. Described by the composer as “a series of mood pictures,” the movements depict the astrological character of all of the known planets of the solar system that were visible from earth at the time. (Colin Matthews, Leonard Bernstein, and others created portraits of Pluto before the distant mass of ice and rock was downgraded to “dwarf planet” status in 2006).

Long before the advent of the Hollywood film score, Holst provided a model for the ultimate cinematic music. Listening to The Planets, we experience a magical, heightened sense of colour and atmosphere. The traditional orchestra is augmented to include alto flute, bass oboe, tenor tuba (often played on a euphonium), organ, two harps, six timpani (two players), a vast percussion section with celesta, and an offstage six-part women’s chorus. In Holst’s suite, the planets are not presented in order of proximity to the sun. Instead, The Planets takes a musical journey which seems to dissolve into the mystical outer reaches of time and space.

Set in 5/4 time, Mars, the Bringer of War feels like a rigid, unnatural march with one too many beats. This music was completed in August of 1914, before the start of the First World War. Yet, its unrelenting ostinato drumbeat takes on the maniacal fervor of a dehumanized society plunging headlong into mechanized battle. The conductor, Sir Adrian Boult, recalled that Holst believed that this perverse march captured the mindlessness and stupidity of war. In the ominous opening bars, col legno (the percussive slap of the wood of the bow against the strings) suggests the grinding of bones. Amid wild, discordant fanfares, Mars pushes to the edge of polytonality with a clash of keys. Colin Matthews writes that the sheer violence and terror of this music in performance “may have surprised [Holst] as much as it galvanized its first audiences.”

According to the astrologer, Noel Tyl, “when the disorder of Mars is past, Venus restores peace and harmony.” Venus, the Bringer of Peace opens the door to this shimmering, serene new world. It begins with a distant, lamenting horn call. A choir of woodwinds, harp, and celesta evoke the radiance of Venus, a bright, reassuring presence in the night sky. Later, the gentle and intimate voices of the solo violin and oboe enter the conversation. The final bars fade away with a sense of childlike innocence.

Mercury, the Winged Messenger is a fleeting, effervescent scherzo. With a swish of motion, ephemeral lines dart around the orchestra, leaving a dazzling display of color in their wake. A single, repeating motif soars to a climax and then evaporates. B-flat major and E major come together to form a momentary bitonal blur. With this music, Holst seems to be importing the sensuous colors of French Impressionism across the Channel.

Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity erupts with a celebration of “abundance of life and vitality.” It’s a frolicking romp which pays homage to the English folksong. In one passage, a gruff and boisterous dance begins in the strings and is then echoed with laughter in the sparkling woodwinds and glockenspiel. All frivolity fades in the middle section (andante maestoso), and we hear one of the most majestic themes in all of English music. It grows into a stately, continuously building procession. Just when we think we have reached the climax, the theme evaporates without resolution, and we return to the village carnival.

Colin Matthews describes Saturn, the Bringer of Old Age as “a slow processional which rises to a frightening climax before fading away as if into the outer reaches of space.” An icy, plodding ostinato chronicles the passage of time with the cruel regularity of sand dropping through an hourglass. Soon, the grim, descending bass line of a funeral march begins, accompanied by a solemn chorale, played by the three trombones. A moment later, we hear the ghostly outline of the Dies irae. In the final moments, terror subsides and time seems to dissolve. Old age drifts into tranquil sleep. Holst wrote, “Saturn not only brings physical decay but also a vision of fulfillment.”

Uranus, the Magician begins with a searing four-note motif. Stated in the brass, this diabolical motif recurs obsessively throughout the movement. Careening between minor and major, this is the music of sorcery. It begins as “a clumsy dance, which gradually gets more and more out of hand.” (Matthews) Later, the music seems to take the form of a deranged British military march.

The final movement, Neptune, the Mystic, returns to irregular 5/4 time. Yet, as the music unfolds, rhythm and meter fade into the background and we are left with sound and color. This atmospheric music, simultaneously eerie, unsettling, glistening, and beautiful, seems to have inspired countless film scores. Haunting dissonances abound. In the days before the premiere, the conductor, Geoffrey Toye, reviewed the score with Holst. Toye pointed to a measure in which E minor and G-sharp minor are heard simultaneously and commented that it was “going to sound frightful.” The composer admitted that the dissonance had sent a chill down his spine, initially. Then, Holst looked at his friend and said, “What are you to do when they come like that?” The final moments bring the hypnotic strains of a celestial, wordless choir of female voices. The music never ends. Instead, the mysterious siren song fades into eternity.

Five Great Recordings

- Holst: The Planets, Op. 32, Charles Dutoit, Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal

- Sir Adrian Boult and The New Philharmonia Orchestra

- Herbert von Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic

- James Levine and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

- Gustav Holst and the London Symphony Orchestra (the first recording from 1923)

This article first appeared on The Listeners’ Club.