Handel’s Messiah Premiere: The Dramatic and Almost Failed First Performance in Dublin

Handel’s Messiah almost never saw the light of day. Its 1742 Dublin premiere was a risky bet that turned into a musical triumph, rescuing Handel’s career and transforming the choral repertoire forever.

It is difficult to imagine today that George Frideric Handel’s Messiah, one of the most enduring and frequently performed choral works in Western music, came perilously close to never receiving its triumphant debut. Though now synonymous with grand concert halls, Christmas traditions, and the iconic "Hallelujah" chorus, the premiere of Messiah in Dublin on 13 April 1742 was preceded by moments of anxiety, financial uncertainty, and public scepticism. The event that has come to symbolise divine inspiration and musical majesty was, at its inception, a modest experiment — a gamble, even — by a composer whose reputation was waning.

Handel in Decline

By the early 1740s, Handel’s fortunes in London were in steep decline. Once celebrated for his Italian operas and adored by aristocratic patrons, Handel found himself out of step with the changing tastes of English audiences. Italian opera was no longer the fashionable obsession it had once been, and rival impresarios vied for public favour. His latest opera ventures had failed to make a profit, and his finances were in disarray. Moreover, the composer suffered a stroke in 1737 which had temporarily paralysed his right arm and affected his ability to compose.

In the face of this personal and professional adversity, Handel turned increasingly toward the genre of the English oratorio — a sacred, dramatic musical form performed without staging or costumes. The oratorio format, which combined sacred themes with operatic grandeur, was both cost-effective and capable of attracting broader audiences. In many ways, Messiah was the culmination of this pivot.

The Libretto: A Radical Departure

The libretto for Messiah was compiled by Charles Jennens, a wealthy and devout patron of the arts. Unlike Handel’s earlier oratorios, which drew from dramatic biblical narratives such as Saul or Israel in Egypt, Messiah was based on a thematic collage of scripture rather than a single story. It unfolds in three parts: the prophecy and birth of Christ, His passion and resurrection, and the promise of redemption. There are no named characters, no conventional drama — only the power of biblical text and Handel’s luminous score.

At the time, some critics found this structure bewildering. The absence of a linear narrative led some to question its dramatic legitimacy, while others found the very idea of placing the sacred text of Christ’s life and resurrection in a theatrical setting offensive. A London performance of Messiah, had it occurred first, might well have been marred by moral outrage.

Dublin: A Calculated Choice

Handel’s decision to premiere Messiah not in London, but in Dublin, was not merely an act of retreat; it was a shrewd move. Dublin was, in the 1740s, an emerging cultural centre with a vibrant musical life, sophisticated audiences, and less rigid expectations than the capital. Moreover, Handel had received an invitation from the Duke of Devonshire, then Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, to visit and present a season of concerts.

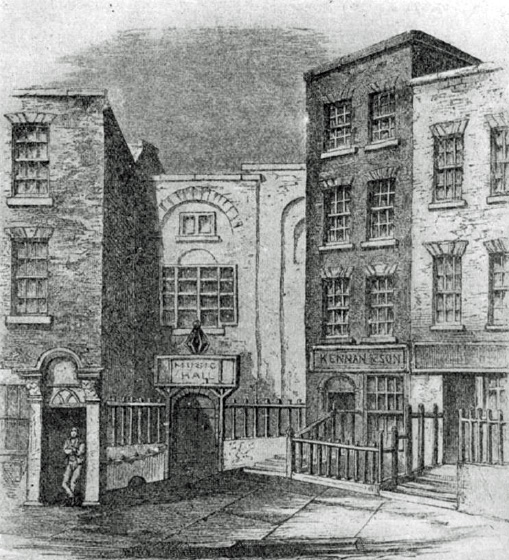

Upon arriving in Dublin in November 1741, Handel found himself warmly received. He quickly organised a series of performances at the Great Music Hall in Fishamble Street, a venue at the heart of Dublin’s bustling cultural life. His concerts were well attended, and a sense of anticipation began to build for the mysterious “new sacred oratorio” that would soon be unveiled.

A Charity Performance

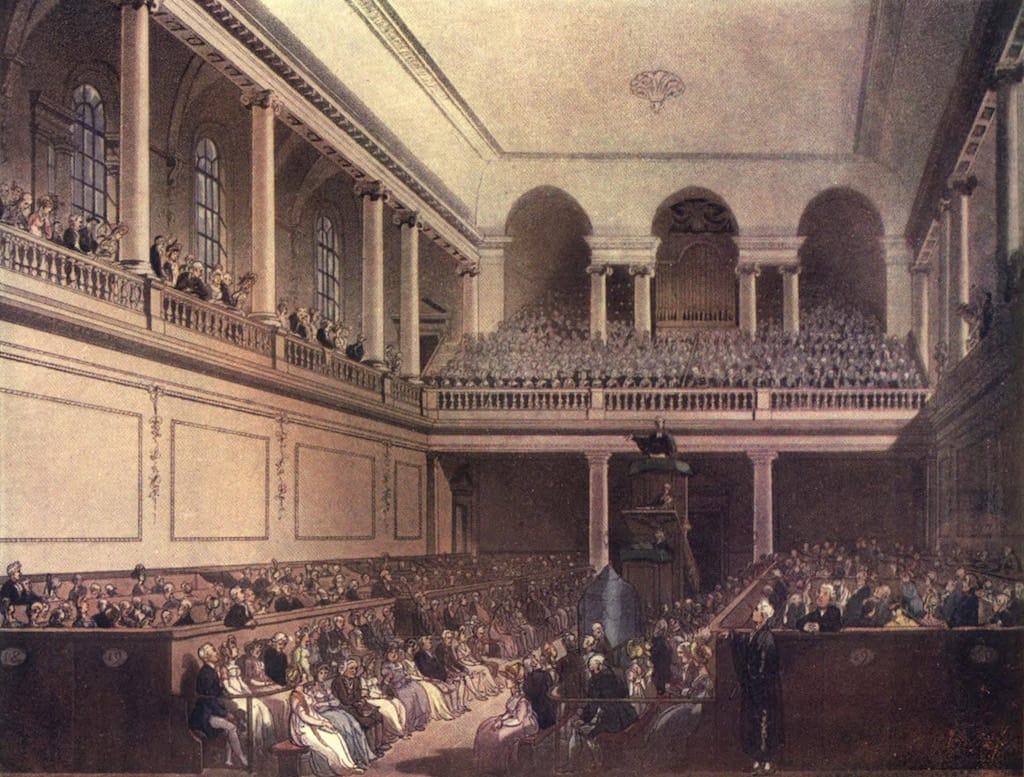

The premiere of Messiah was conceived not only as a concert but as a charitable event. Proceeds were to be divided among three beneficiaries: the Society for Relieving Prisoners, the Mercer’s Hospital, and the Charitable Infirmary. This alignment with philanthropy helped to placate potential religious criticism. Still, Handel and the organisers faced a logistical hurdle — the size of the venue.

In an unusual move, the public was asked to forgo their hoops (the wide skirts fashionable at the time) and gentlemen were requested to leave their swords at home in order to maximise seating. Such was the enthusiasm that over 700 people squeezed into the hall on the night of 13 April 1742.

The Performance: A Revelation

The audience that evening witnessed something extraordinary. Conducting from the harpsichord, Handel led a chorus of fewer than 40 voices and an orchestra of modest scale by modern standards. Yet the impact was immediate. From the gentle, pastoral grace of “He shall feed his flock” to the emotional gravity of “He was despised,” and the triumphant splendour of the “Hallelujah” chorus, Messiah astonished its listeners.

One contemporary reviewer declared it “the finest composition of musick that ever was heard.” Lady Wellesley, sister of the composer Thomas Arne, reportedly wrote that the performance “exceeded anything I ever heard before.” The musicians, many drawn from Dublin’s best ensembles, rose to the occasion with what appears to have been deep conviction and sensitivity.

The performance raised over £400 for charity — an immense sum at the time — and helped release 142 debtors from prison. Perhaps more importantly for Handel, it marked the beginning of his rehabilitation as a composer of consequence and vision.

A Reception Less Kind in London

When Messiah was finally performed in London in 1743, the reception was markedly more cautious. While the music was admired, there were murmurs of disapproval at its religious content being sung in a secular theatre (Covent Garden). Some clergy deemed it inappropriate for sacred texts to be “profaned” by such public performance. The composer, aware of the sensitivities, avoided using the title Messiah in advertisements, instead referring to it obliquely as “A Sacred Oratorio.”

Even King George II’s supposed standing during the “Hallelujah” chorus — the origin of the now traditional audience custom — is wrapped in legend and uncertainty. Whether he rose out of reverence or simple discomfort is unknown, but the myth endures.

It was not until later revivals, particularly those associated with charitable causes such as the Foundling Hospital in London, that Messiah began to enjoy widespread and unquestioned popularity.

Legacy and Influence

The story of Messiah’s premiere is one of artistic courage, strategic calculation, and eventual vindication. Handel, once dismissed as an operatic relic, secured his legacy through a work that combined musical brilliance with spiritual profundity. Today, Messiah is performed in cathedrals, concert halls, and community spaces across the globe, often with amateur and professional forces alike, continuing its dual mission of art and charity.

In some ways, the modest premiere in Dublin reflects the oratorio’s deeper themes: humility, redemption, and glory not achieved through pomp, but through sincere expression. What was nearly lost to neglect and indifference emerged as one of the high points of European music — a triumph not only of sound but of the human spirit.