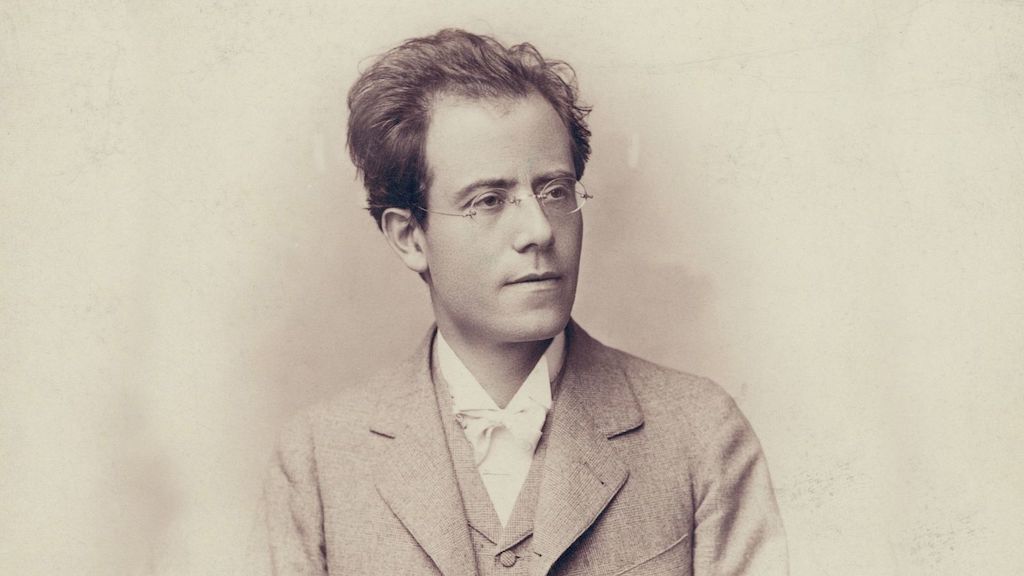

The works of the composer Gustav Mahler (1860–1911) are among the most often played in many orchestras’ repertoire. This was not the case during his lifetime, however, when he was much more popular as a conductor than a composer – his critics finding his compositions too different, too complex and, as one critic put it, “dangerous”.

One champion of Mahler after the second world war was the composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein (1918–1990), who played an important part in the posthumous breakthrough of Mahler’s music. Bernstein’s love of Mahler has been dramatised in two films this year, Maestro and Tár.

In Maestro, a biopic of Berstein, the conductor is seen wildly conducting Mahler’s monumental Symphony No.2. In Tár, the fictional celebrated conductor at the heart of the film credits Bernstein as both her early inspiration and her mentor. The film follows Lydia Tár as she, like Bernstein before her, completes the cycle of Mahler’s symphonies with a live recorded performance of his Symphony No.5.

Both these films have brought Mahler to a new audience and, since the release of Tár, the 70-minute Fifth Symphony, in particular, has gained a new life and new fandom.

Mahler’s symphonies are very of their time. Produced in the late 1800s and early 1900s, classical music was making the shift from the late-Romantic to early Modernist. They are, depending on which side you sit, either a sincere piece of late-romantic music or an ironic modernist jibe at late-romantic music.

If you are a lover of late-Romantic, his symphonies can be heard and understood as manifestations of romantic nostalgia and full of bombast. But if you are a modernist, you can hear in them premonitions of the tensions and fissures typical of that genre.

The two symphonies are quite different. The Fifth Symphony has a special position in his oeuvre because of a stylistic rift between it and its four predecessors that highlights these two ways of understanding Mahler.

The Fifth: A symphonic transition

The Fifth, Sixth and Seventh symphonies, composed between 1901 and 1905, form a group of works that differ from that heard in the first four symphonies in terms of structure and expression. What sets the latter works apart is their less linear development of ideas and structures.

In the later symphonies, Mahler often surprises his listeners with drastic and sudden shifts in texture and instrumentation. Mahler’s first four symphonies look back to their Romantic heritage in a tender manner; while the three middle symphonies, five, six and seven, are looking forward in time, anticipating the brokenness of modern man and art.

The Fifth’s shortest movement, which is also the most prominent of this symphony, is the famous Adagietto. This movement is a dreamy and passionate piece that is the most coherent and easy to grasp of the entire work, even though its harmonic cadenzas often lead to nothing.

In it, the heavy brass section is kept silent and there is no bass register. The strings and harp play without interruption, creating a dense atmosphere. The movement is said to represent Mahler’s love song to his wife Alma, whom he married while working on the symphony.

The Adagietto is what audience members hear throughout Tár. It also appeared in Luchino Visconti’s 1971 film Death in Venice and a recording of Bernstein conducting the Vienna Philharmonic can be heard in Maestro.

The Fifth’s first movement with the instruction “Like a funeral march” is not, like in many famous symphonies, a piece of thematic conflict or dramatic development but almost the opposite of it. The march, which starts with a solo trumpet fanfare that alternates with the violent sound of the whole orchestra, is the beginning and the end of it.

The breakthrough?

Bleak sections in the middle of the movement enhance the brooding atmosphere of the piece rather than contrasting it. The second movement has the same gloomy tone. In it, Mahler employs what musicologist Bernd Sponheuer has identified as a primary form category in his works: the breakthrough.

After a long rhythmically rather indistinct and, in terms of expression, swaying section, a solemn choral in the brass seems to lift the listener into another sonic environment, above the shadowy, amorphous world that they had been dwelling in until now.

A stable harmonic and melodic structure appears like the promise of having reached a safe haven after a long sailing in the dark. And yet, again, without any transition, this stability evaporates and the movement ends with a short, suffocated whimper.

In this movement, Mahler impedes the breakthrough concept that he had developed in his former symphonies. The finale most often describes a victory after the struggles over the forces that were unleashed in the former movements, which is the case of famous symphonies from Beethoven and Bruckner. However, in the Fifth, the finale again structurally quite static like its opening. It ends not in triumph but just in loudness. Again, like in the introduction, there is not so much development but the initial idea is examined from different angles.

In the Fifth, Mahler quotes Wagner, Beethoven, Austrian military marches, trivial dance music and his own songs. Technically, it is much more complex than his former works, especially considering its polyphonic structures and so much more demanding for the instrumentalists.

Mahler, who was an experienced and industrious opera conductor, claimed to have pushed the technical boundaries of the individual instrument groups to the extreme in the Fifth. The disparity of ideas is enormous and culminates in moments when several different themes are played ruthlessly at the same time.

As Mahler told the Finnish composer Jean Sibelius (1865–1957), for him his symphonies had to contain the whole world and the Fifth is certainly a world on its own. In the piece the most contradicting ideas collide in a spectacular manner: nostalgia with irony, triumph with collapse, brutality with affection, the subtle with the banal, the innovative with the worn out and utopia with crude realism.

By Martin Knust, Professor of Musicology, Linnaeus University. This article first appeared on The Conversation.