Gershwin and Schoenberg: An Unlikely Friendship

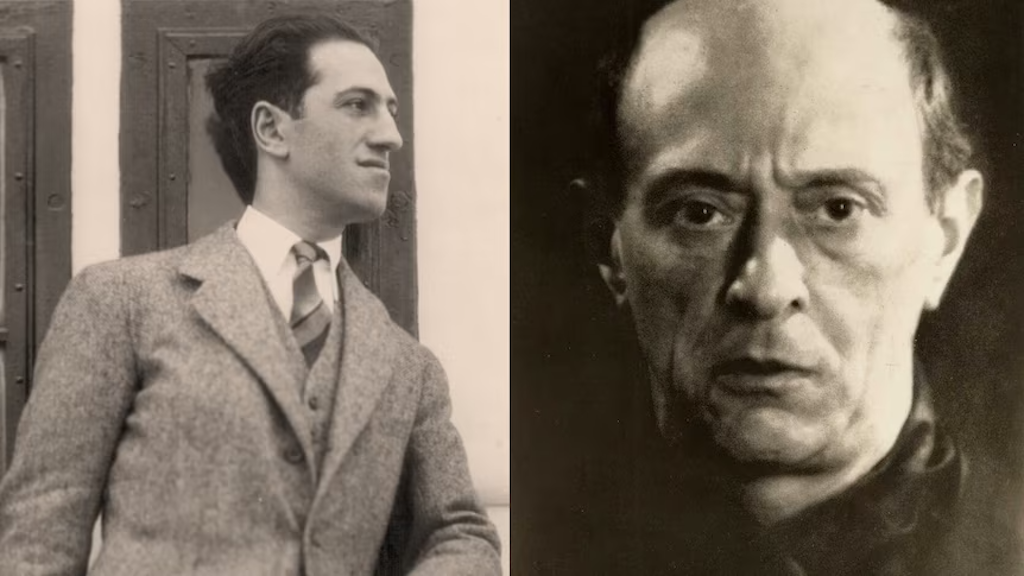

George Gershwin and Arnold Schoenberg formed one of music history’s most unexpected friendships. Their bond in 1930s Los Angeles bridged classical modernism and American jazz, revealing how mutual respect can transcend genre, culture, and artistic philosophy.

The history of Western music is full of surprising alliances, but few are as intriguing or as revealing as the friendship between George Gershwin and Arnold Schoenberg. On the surface, the two composers inhabited completely different artistic worlds. Gershwin was the suave American songwriter who introduced jazz rhythms into the concert hall and brought the sparkle of Tin Pan Alley to international audiences. Schoenberg, in contrast, was the uncompromising modernist who developed the twelve tone method and became a symbol of radical musical thought. Yet in 1930s Los Angeles, these two towering figures discovered that they were not only neighbors but also kindred spirits. Their friendship, built on mutual respect and a shared curiosity about the possibilities of music, became an extraordinary meeting point of two artistic philosophies.

A Meeting in Los Angeles

The story begins in 1934 when Schoenberg, who had fled the rising tide of anti-Semitism in Europe, settled in Los Angeles with his family. For the first time in decades, the famously intense composer found himself in a world filled with bright sun, palm trees, and the glamour of Hollywood. The city’s artistic landscape was expanding rapidly and attracting musicians, film studios, painters, and writers from both coasts and across the Atlantic. Gershwin was already visiting Los Angeles frequently and would soon spend long stretches of time there while working in the film industry.

It did not take long for their worlds to come together. Gershwin, who admired Schoenberg deeply, arranged to meet him through mutual acquaintances. He was captivated by the older composer’s intellect and by his unwavering artistic principles. Schoenberg, for his part, was taken by Gershwin’s sincerity, his enthusiasm, and his natural talent. He believed that critics often underestimated Gershwin’s abilities because of his association with popular music.

Soon the two composers were meeting often, both for relaxed conversations and for their now legendary tennis matches. These encounters cemented their friendship and later became symbolic of the unlikely yet remarkable bond between the American master of melody and the European pioneer of atonality.

The Tennis Court Symbiosis

Among the many stories that survive, none is as charming as the image of Gershwin and Schoenberg facing off on the tennis court. Gershwin was athletic, competitive, and wonderfully social. Schoenberg approached the sport with the same seriousness and precision he brought to composition. Their tennis games reflected their personalities completely. Gershwin played with exuberance and flair, while Schoenberg played with determination and focus.

Their matches were spirited, frequently humorous, and occasionally intense. Yet they created a neutral space where the hierarchies of European modernism and American popular culture disappeared. After their games, the two often retreated to one of their homes for long evenings filled with discussions about music, art, teaching, and the direction in which the musical world was moving.

It is revealing that Schoenberg respected Gershwin not as a curiosity but as a genuine colleague, someone he believed possessed what he called “the soul of a composer.” He felt that Gershwin had the potential to do even more ambitious work if he chose to explore deeper studies in composition.

A Discussion About Lessons

Gershwin, who was always eager to grow, asked Schoenberg if he would consider giving him composition lessons. He knew that Schoenberg had trained some of the most remarkable young musicians of his era, including Alban Berg and Anton Webern, and he hoped that studying with him might expand his own artistic vocabulary.

Schoenberg declined, though he did so with great generosity. His reason has become a familiar part of musical history. “I would only make you a poor Schoenberg,” he said, “and you are such a good Gershwin already.”

His response was thoughtful and perceptive. Schoenberg recognized that Gershwin’s genius came from his natural and instinctive blend of classical structure and jazz idiom, a blend that could not and should not be reshaped into twelve tone rows. His refusal was not a discouragement. It was an acknowledgment that Gershwin’s originality was too important to risk altering.

This moment illustrates not only Schoenberg’s respect for Gershwin, but also the philosophical differences that defined both men. Gershwin believed in spontaneity, instinct, and the organic fusion of styles. Schoenberg believed in systems, rigorous structure, and inner necessity. Yet neither man viewed the other’s philosophy as lesser. In fact, their bond grew out of their shared conviction that music, in all its forms, deserved exploration.

Different Paths, Shared Convictions

Despite their contrasting musical languages, Gershwin and Schoenberg had more in common than it might initially appear. Both were Jewish immigrants or children of immigrants. Both emerged from modest backgrounds and achieved international success through relentless work. Both experienced periods when critics misunderstood their artistic intentions.

Most importantly, both were innovators. Gershwin’s fusion of jazz and classical music in works like “Rhapsody in Blue,” “An American in Paris,” and “Porgy and Bess” demonstrated a restless imagination that challenged traditional categories. Schoenberg, through the development of twelve tone technique and his rethinking of harmony and form, transformed centuries of musical tradition into something entirely new.

Innovation is often a lonely pursuit. In each other, they found someone who understood what it meant to stand apart from the mainstream.

Creative Cross-Pollination

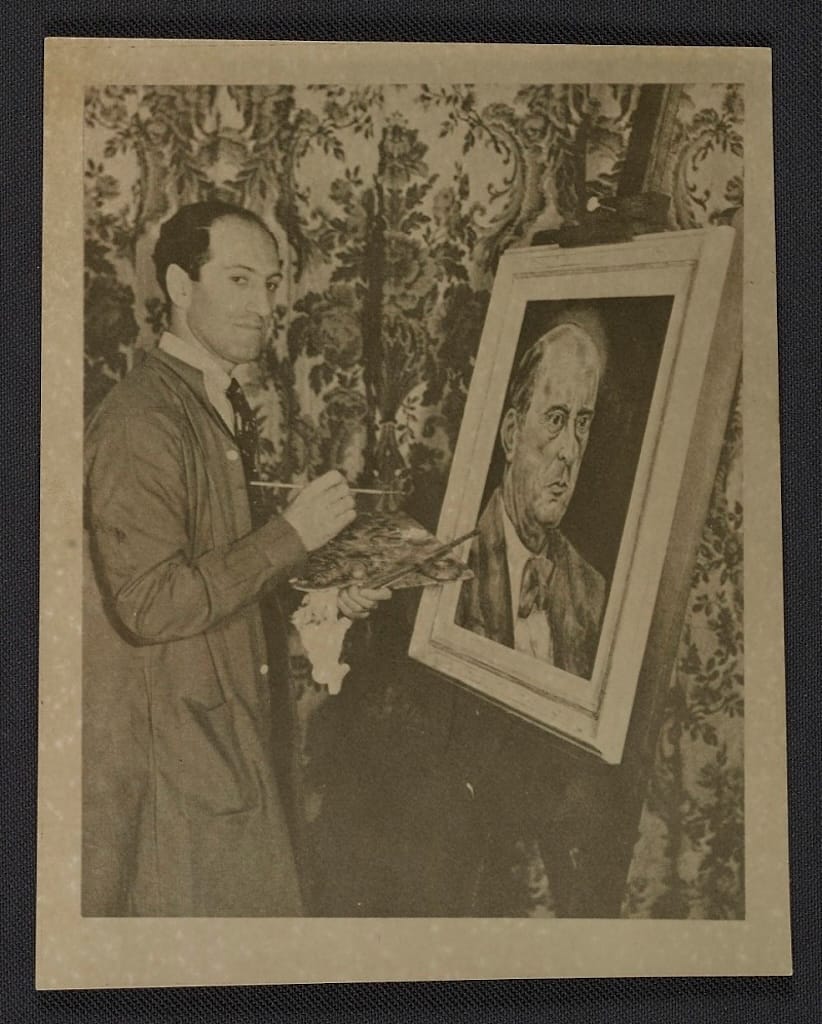

Although they did not collaborate directly, their friendship influenced both composers in subtle ways. Gershwin gained exposure to European modernism in a way that was deeper than anything he had previously experienced. At a time when American critics sometimes dismissed him as merely a composer of popular songs, Schoenberg treated him as an equal. This respect may have strengthened Gershwin’s confidence as he pursued large scale compositions.

Schoenberg, in turn, gained a greater appreciation for the vitality of American music, especially jazz. He did not incorporate jazz into his own compositions, but he admired Gershwin’s rhythmic language and believed that jazz represented a meaningful and authentic cultural voice.

Their friendship also created a symbolic bridge between musical cultures at a moment when the divide between serious and popular music was sharply drawn. Their rapport suggested a more fluid musical world in which tradition and innovation, Europe and America, and classical and popular music could exist side by side.

The Final Chapter

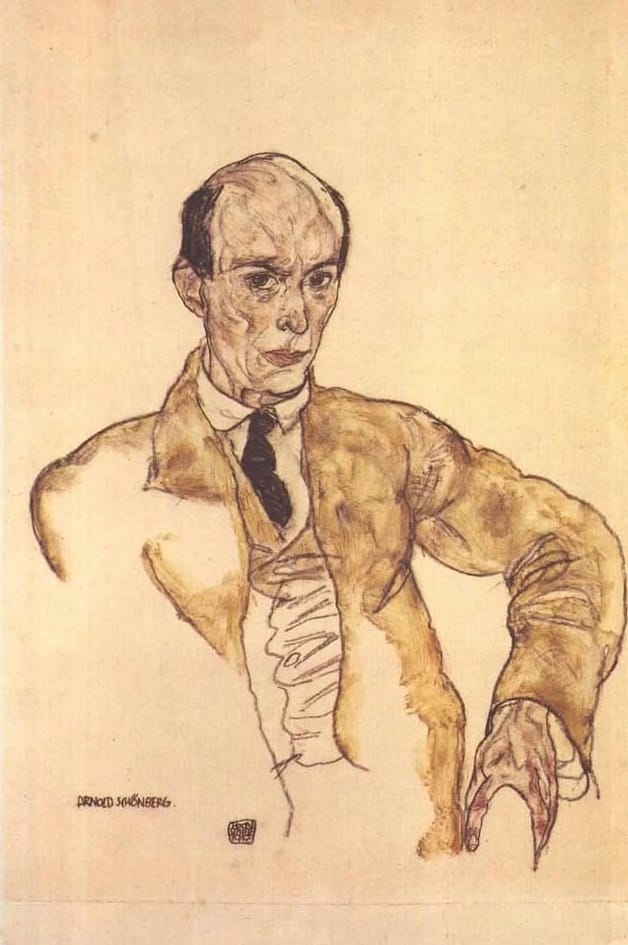

The friendship ended far too soon. Gershwin died suddenly in 1937 at the age of thirty eight because of a brain tumor. The loss devastated Schoenberg, who wrote a moving tribute expressing his admiration and sorrow. He reiterated that Gershwin possessed rare talent and that critics had failed to understand the depth of his music.

Schoenberg later created a portrait drawing of Gershwin, a deeply personal artistic gesture that remains a poignant reminder of their connection.