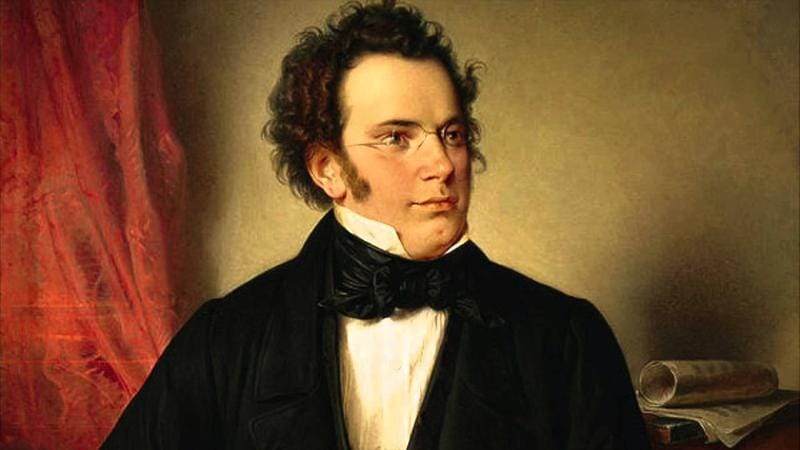

Franz Schubert and His Circle of Friends

Franz Schubert lived the quintessential life of an urban bachelor. He rejected the restraints and dependence of family life and found sustenance and camaraderie in a close, but ever-changing circle of friends. Perpetually short of money, he lived with various roommates, hung out in pubs and drank heavily. Schubert flirted with leftist political movements, women and men, and frequented brothels for sexual gratifications. Already at the age of 11, serving as a choirboy in the imperial court chapel, he cemented friendships that would last well into his adult life. And he would participate in numerous private and informal gatherings within his circle of friends, freely exploring art, politics, literature and music. Eventually dubbed “Schubertiade,” these meetings featured poetry readings, dancing, and other sociable pastimes alongside the glorious music of Schubert. So let’s meet some of the characters and personalities from Schubert’s circle of friends.

The lawyer and musician Anselm Hüttenbrenner (1794–1868) studied composition with Antonio Salieri, and he was a favorite friend of Schubert. Hüttenbrenner was given to a bit of hero worship, and Schubert would ironically remark, “that fellow likes everything of mine.” Hüttenbrenner would arrange Schubert symphonies for piano, he made sure that everything was properly engraved, and he even corresponded with foreign publishers on behalf of Schubert. Since Hüttenbrenner was an accomplished pianist, Schubert enjoyed playing compositions for four hands with him, and he would praise the purity and expressiveness of Hüttenbrenner’s play, and the quickness with which he read music at sight. Hüttenbrenner wrote his memoirs of Schubert for Franz Liszt in 1854, and Schubert crafted a beautiful set of variations on a theme of his friend. Hüttenbrenner’s reputation as a friend of Schubert has suffered severely from his handling of the “Unfinished Symphony,” but his first requiem in C minor was performed on a number of occasions in tribute to Schubert, including the memorial service on 23 December 1828.

The Viennese dramatist Eduard von Bauernfeld (1802-1890) was the playwright in residence at the Burgtheater in the 1830s, and he was one of Schubert’s closest friends between 1825 and 1828. Bauernfeld’s diary and reminiscences provide an important primary source of information about the last years of Schubert’s life. Bauernfeld pointedly describes Schubert’s intimate feeling for literature: “he was anything but unversed and the way he understood how to interpret, with inventiveness and vitality, the different poetic individualities, like Goethe, Schiller, Wilhelm Müller, G. Seidl, Mayrhofer, Walter Scott and Heine, how to transform them into new flesh and blood and how to render faithfully the nature of each one by beautiful and noble musical characterization—these recreations in song should alone be sufficient to demonstrate, merely by their own existence and without any further proof, from how deep a nature, from how sensitive a soul these creations sprang. A man who so understands the poets is himself a poet!” Schubert set a handful of original Bauernfeld poems, and he used Bauernfeld’s translation of Shakespeare for his song “An Sylvia.” At the time of his death, Schubert also left an unfinished opera “Der Graf von Gleichen” to a libretto by Bauernfeld.

Josef Kenner (1794–1868) came to Vienna in 1811 to study at the Imperial College in Vienna. There he met the 14-year old Schubert as a fellow student. Many years later he described those extraordinary times in the freezing cold piano room of the Imperial College. “It was there that his earliest compositions were first tried out and discussed and it was there that I was surprised by the dedication of the “Liedler,” which was handed over to me. You cannot possibly imagine how humble I felt at this mark of distinction, at this dedication, and at the truly friendly way in which it was done, because you know neither my admiration for Schubert’s artistic greatness nor my opinion of my own very humble merits. I did indeed know that Schubert craved merely for words which were fairly manageable and that therefore I had no reason to be in the least conceited because mine were chosen.” Schubert had set three Kenner poems, and they stayed friends for the rest of Schubert’s life. Kenner eventually blamed Franz von Schober for encouraging Schubert into the pathways that led to his final illness.

By Georg Predota. Republished with permission from Interlude, Hong Kong.