Franz Liszt: Life, Legacy and Lasting Influence on Music

Discover the extraordinary journey of Franz Liszt—from his childhood prodigy years in Hungary to his revolutionary virtuosity, landmark compositions and role as teacher, impresario and advocate for new music—tracing the enduring impact he left on the musical world.

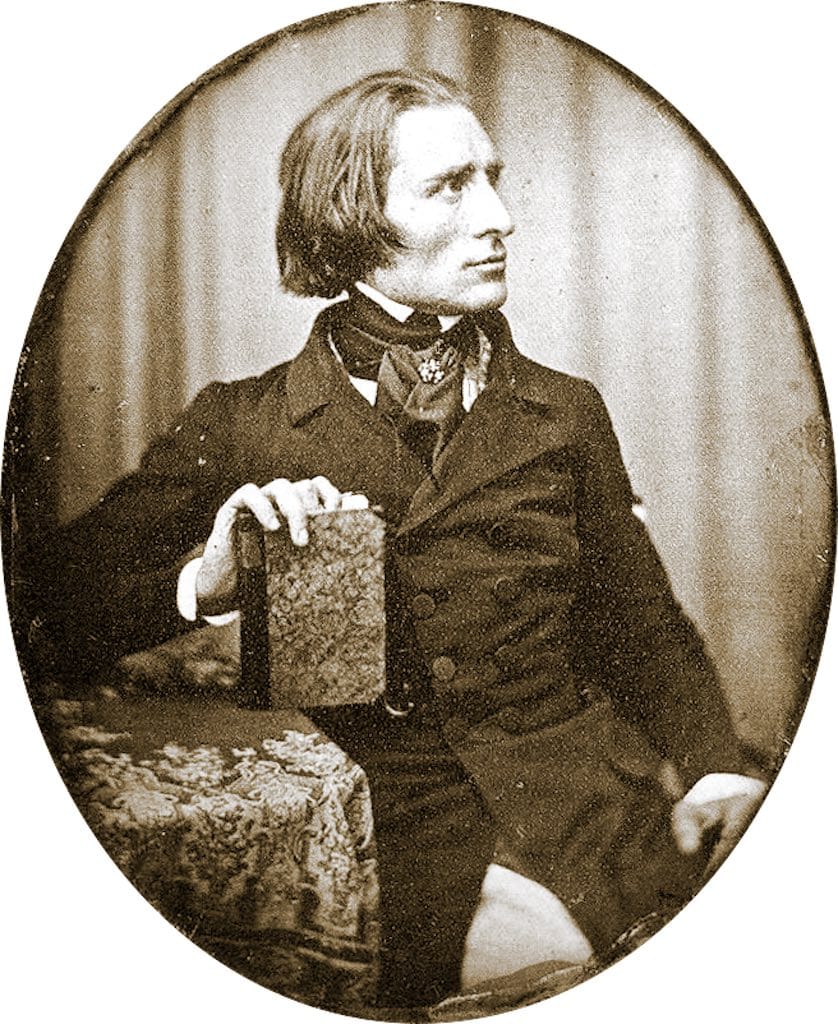

Franz Liszt (1811–1886) remains one of the most towering figures in the annals of Western music. A prodigious virtuoso, pioneering composer and magnetic showman, Liszt rewrote the rules of pianism and laid the groundwork for many of the musical trends that followed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In exploring his life and legacy, one encounters an artist who transcended mere performance to become a visionary mentor, cultural impresario and champion of his contemporaries.

Early Years in Hungary and Rapid Rise

Born on 22 October 1811 in the small town of Doborján (now Raiding, Austria; then part of the Kingdom of Hungary), Liszt was the son of Adam Liszt, a steward on a noble estate, and Anna Liszt (née Maria Anna Lager). From the outset, young Franz exhibited extraordinary musical gifts. His first public concert took place in Vienna in March 1823, when he was only eleven years old; Beethoven is said to have praised the boy, reportedly declaring, “Truly, he is a marvel.”

His family soon settled in Paris, where Liszt studied under the tutelage of Frédéric Chopin and Ferdinando Paër, among others. By his late teens he was already touring Europe, dazzling audiences with an ease and flair at the keyboard that no one had ever quite seen before. Unlike the more reserved recitals of his predecessors, Liszt’s performances were electrifying affairs—he played from memory, improvised entire cadenzas on the spot, and seemed constantly on the brink of transcendent ecstasy. This was the birth of “Lisztomania”: the near-frenzied adulation of audiences who treated him less like a mere musician and more like a rock star.

Virtuoso Par Excellence and Innovations in Technique

Liszt’s virtuosity was underpinned by a formidable technique that he constantly refined and expanded. He introduced new hand positions and fingerings, explored the extremes of sonority and pedal use, and made full use of the piano’s growing capabilities. His Études d’exécution transcendante (Transcendental Études, 1851), for instance, are not merely technical exercises, but miniature tone poems that combine formidable demands on the player with rich poetic character.

Beyond pure technique, Liszt pioneered the solo piano recital as we know it today. Prior to his time, keyboard players often performed in salons or chamber settings. Liszt transformed the concert hall into his own personal temple of music, standing centre stage at the piano—often turned sideways so that his audience could watch his hands in action. This model was quickly adopted by subsequent generations of pianists, embedding the solo recital firmly in the concert tradition.

Compositional Output: From Hungarian Rhapsodies to Symphonic Poems

While Liszt’s reputation initially rested on his prowess as a performer, his contribution to composition is equally profound. His Hungarian Rhapsodies, a set of nineteen works composed between 1846 and 1885, distilled into music the spirit and folk rhythms of his native land. Though sometimes criticised for their occasional superficial exoticism, they remain staples of the repertoire—showcases of virtuosic bravura and colour, yet also imbued with genuine melodic charm.

More revolutionary, however, were Liszt’s contributions to the symphonic poem. Beginning with Les Préludes (1854), he fashioned a novel orchestral form that wove together a loose programme—a poetic or narrative concept—with continuous, thematically connected music. In doing so he liberated orchestral writing from the rigid structures of sonata-allegro and four-movement symphony. This approach influenced composers such as Richard Strauss and Pavlovich Tchaikovsky, opening new avenues for musical expression.

Liszt’s late works, composed after he ceased touring regularly in the 1860s, reveal an experimental, forward-looking mind. Works like Nuages gris (1881) and Bagatelle sans tonalité (1885) toy with ambiguous harmonies and proto-atonal elements, foreshadowing the harmonic revolutions of Debussy and Schoenberg. These pieces display a composer perpetually restless, always probing the boundaries of tonality and form even as his public fame continued to wax.

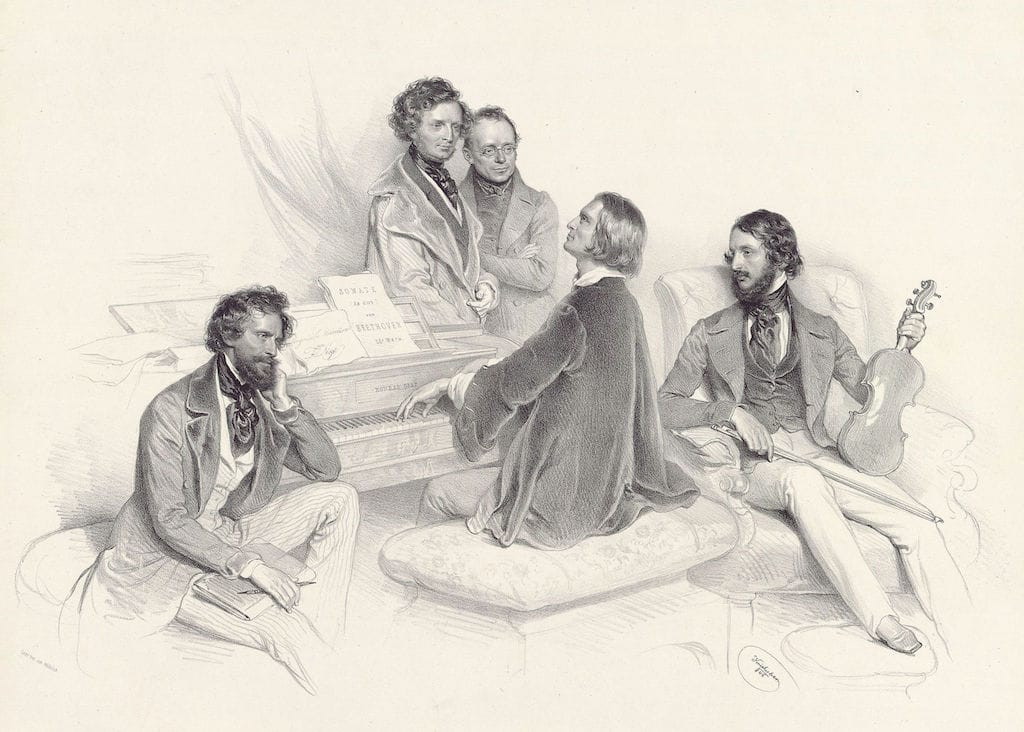

The Weimar Years: Conductor, Teacher and Cultural Patron

In 1848 Liszt settled in Weimar at the invitation of Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna of Russia. There he served as Kapellmeister (music director) until 1861, championing the works of Berlioz, Wagner and Schumann at a time when they were not yet universally accepted. He conducted the first performances in Germany of Berlioz’s Faust and Wagner’s Faust-Ouvertüre, fervently advocating his friends’ music—and in doing so, helped shape the European musical landscape.

Liszt was equally devoted to pedagogy. He attracted a circle of students in Weimar, providing lessons, masterclasses and encouragement. His pupils included Hans von Bülow (later his son-in-law), Carl Tausig and Alexander Siloti—all of whom became influential pianists and teachers in their own right. Through them, Liszt’s methods and musical ideals disseminated across Europe, seeding a lineage of pianistic tradition that endures to this day.

Personal Life and Spiritual Quest

Liszt’s personal life was marked by intensity and change. In 1847 he took up a liaison with the Countess Marie d’Agoult, with whom he had three children. Later, he married Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein, although the union met ecclesiastical obstacles and eventually dissolved. In his later years, Liszt grew more contemplative and devout; he received minor orders in the Catholic Church and was often referred to as “Abbé Liszt.” His final years were spent between Rome, Weimar and Budapest, where he continued to compose, teach and serve as an arbiter of taste in musical matters.

The Budapest Academy and the Nationalist Turn

Liszt’s final great institutional legacy was the founding of the Royal Hungarian Academy of Music in Budapest in 1875. Although his direct involvement waned over time, the academy embodied his vision of rigorous artistic training infused with a nationalist spirit. Under the baton of his former pupil Ferenc Erkel, the institution nurtured a generation of Hungarian musicians—among them Zoltán Kodály and Béla Bartók—who would further explore and elevate indigenous folk traditions.

Influence and Commemoration

Franz Liszt’s death on 31 July 1886 in Bayreuth came at a moment of profound transformation in European music. Yet his influence continued to resonate. Pianists still invoke his revolutionary technical feats and poetic nuance; orchestras programme his symphonic poems; composers refer to his harmonic experiments as direct antecedents of modernism.

Liszt’s spirit of innovation also lives on in the festival culture he helped to create. His early “Piano Recital” model presaged the recital series that now anchor concert seasons worldwide, while his Weimar soirées foreshadow the composer-centred festivals—Wagner’s Bayreuth and Berlioz’s concerts at the Paris Conservatoire among them—that would shape nineteenth-century musical life.

Moreover, Liszt’s role as a champion of fellow composers established a paradigm of artistic solidarity. His advocacy for Berlioz, Schumann and Wagner illustrates a generosity of spirit that contrasts sharply with the competitive ethos often associated with the concert stage. In today’s world of specialist repertoire and niche audiences, his broad-minded enthusiasm for new music remains a challenge and an inspiration.

To survey the life of Franz Liszt is to traverse a panorama of nineteenth‑century music: from the aristocratic salons of Vienna and Paris to the grand concert halls where audiences wept and swooned; from the intimate salon pieces for piano to vast orchestral canvases that foretold the symphonic poems of the modern era. As performer, composer, teacher and cultural impresario, Liszt forged pathways that countless others would follow and expand.