Folksongs and Fairytales

In our infancy we are told fairy tales, and these stories retain a great power over us throughout our lives.

In many ways the tenets of fairy tales and folk legends are the characteristics of all great music, because all great pieces are fundamentally stories. Calvino writes that in folk tales “There must be fidelity to a goal and purity of heart, values fundamental to salvation and triumph. There must also be beauty, a sign of grace that can be masked by the humble, ugly guise of a frog; and above all, there must be present the infinite possibilities of mutation, the unifying element in everything : men, beasts, plants, things. “

It’s fitting, somehow, that when composers tried to create a national identity for themselves, that they went back to the folk tunes and stories of the past and subsumed them into their music.

When Chopin became a political exile in France in 1831 after the November Uprising, his compositions based on national Polish dance forms and folk tunes (the Polonaise, Mazurka) as well as his four Ballades , which were based on poems by Adam Mickiewicz, expressed his sense of loss and pain at having to be away from his home. I think these pieces feel so touching and intimate because they are full of the nobility and romance, the sense of adventurous narrative that we know from fairytales – but our protagonist is on the losing side and this disappointed romanticism is very moving.

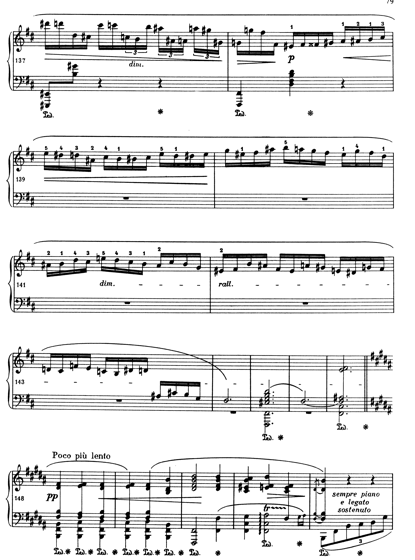

Let’s take the transition to the middle section of one of his most extraordinary pieces, the Polonaise-Fantasie :

Until this point the Polonaise has been developing and becoming more and more agitated – now, it’s as if the music is circling around itself, desperate for some resolution, and this theme is not a virtuoso display, it’s hard work and painstaking, full of chromatic clashes and the exhaustion of finding no release. The Polonaise has been ‘betrayed’ – when we finally arrive at the bottom of the run it feels like a resignation, as if there is nowhere else to go. But then! It’s as if a prophet speaks (in a whisper) and he reveals to us the profound heart of the piece, the “moral of the story”. At the end of the piece, after the heroic and celebratory coda, there is one more murmured, gnarly, chromatic interruption :

For me, it is as if Chopin is reminding us that this epic piece is tinged with despair and loss. His emotional landscape is completely opposed to the exuberance and forthrightness of Wagner ‘s Nordic fairytales (with apologies to Wagner nuts). Even the four Ballades, which were inspired by heroic poems, are deeply introspective.

A century later, Szymanowski, who revered Chopin and saw him as the father of Polish music, would follow in his footsteps and incorporate Polish folk dances from the highland regions into a new harmonic style.

For Janacek, one of the composers closest to my heart, Moravian folk music and fairy tales came to dominate his inner world and were his “constant love”. Much of his music is based on his transcriptions of speech rhythms and over three thousand songs which he collected from Moravia (and all over Europe) and is completely unique in its sincerity and intensity.

He writes:

“I have lived in folk song from childhood. In folk song, there is the whole man: body, soul, landscape, all of it, all…..If I grow at all, it is only out of folk music, out of human speech…”

Unlike Chopin, Janacek was not an exile from his homeland but was trying to establish his own cultural language and to be free of the dominant musical language of the Austro-German tradition as well as the political dominance of the Austrian Empire. In some sense I feel that his music is also full of the defiance and passion of the betrayed, the unrequited lover, the underdog, which makes it all the more poignant. One of his most dramatic works is the piano cycle “On an Overgrown Path”, originally a set of arrangements of Moravian folksongs for the harmonium, and whose title comes from a traditional Moravian wedding song, the bride lamenting that ‘The path to my mother’s has become overgrown with clover’.

The whole cycle is written in the shadow of profound grief ; Janacek wrote to a friend “Perhaps you will sense weeping in it… the premonition of certain death”, and even the more gentle pieces are quickly derailed or viciously interrupted.

There is something so literally tactile and sensuous about Chopin’s masterly writing for the piano so that the player really feels the point where touch, emotion, and harmony meet. Janacek’s relationship to the piano seems more gnarly and complicated – as one of my teachers told me, “Janacek makes your technique worse” (or perhaps he just meant mine?) – but essentially I think that Janacek’s ferocity of feeling is something that is a physical sensation too. The Capriccio , for example, is written for a bizarre ensemble : Piano Left-hand, flute, two trumpets, three trombones and tenor tuba. Truly, a band of embarrassing losers – the instruments picked last for sports teams. But this is precisely why the piece is so effective ; its vulnerable tenderness, capriciousness, triumph of determination in the final climax is all written into the instrumentation. Everyone has been cast in the wrong roles, but they are playing them with total conviction.

I just want to mention one final example which is Bartok’s Third Piano Concerto, written for his beloved wife. This is his swan song, written when his health was terrible and the Second World war was still raging. The outer movements are most inspired by Hungarian folk songs and pentatonic scales and modes, which Bartok considered central to traditional Hungarian music and of which he had collected thousands of examples in his many years as an ethnographer and collector of folk tunes.

The second movement begins like a prayer, marked adagio religioso , but in the middle section, Bartok transcribes the songs of the birds that he heard every morning in the countryside of New York. Only a fragment of his manuscript exists, but next to the bird theme there is an annotation “ Parting in peace”. It is maybe his most poignant and touching compositions, full of longing. In his last days he told his son Peter, “I am only sorry that I have to leave with a full trunk”.