Reconciliation Through Music: Childhood Comics Come to Life

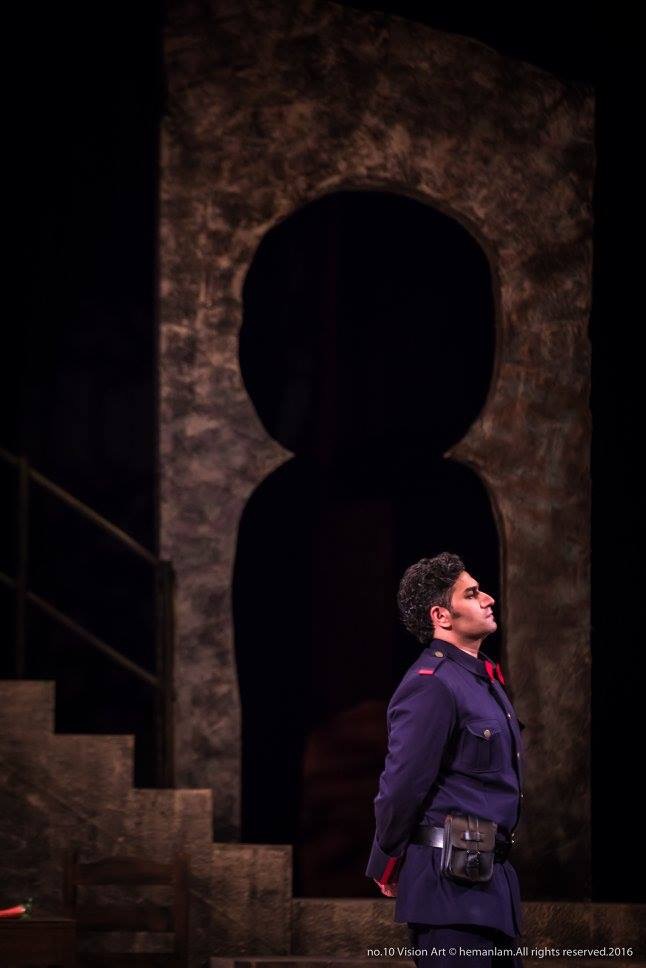

Ravi Shankar’s opera Sukanya receives its world premier with a four city UK tour in May 2017. The work is a collaboration between the Royal Opera House of Covent Garden and the London Philharmonic Orchestra. It takes as its subject a story from the Mahabharata which tells the tale of Sukanya, a beautiful young princess who is offered as a wife to an old sage as recompense for her accidentally blinding him. Through the course of the tale, she exhibits integrity, virtue and an unshakeable sense of duty for which she is rewarded. I have the honour of performing the role of the wronged sage and will be making a series of debuts with my involvement in this work including debuts for the role, each venue on the tour, two companies and the U.K.

David Murphy: conductor

Suba Das: stage director

Susanna Hurrell: Sukanya

Alok Kumar: Chyavana

PRODUCTION

Royal Opera House

London Philharmonic Orchestra

BBC Singers

Aakash Odedra Company

But more dizzying than the honour associated with being a part of this production is the fact that I have known the tale of Sukanya since I was a child. The story was one of many in my collection of Amar Chitra Katha comics which were passed down to me by my cousin, and which I devoured to the point of memorisation. So why does this cause me pause to reflect? Because I find it cosmically amusing and entirely appropriate that a story from my youth and cultural origin should be the artistic vehicle through which I am to make a significant professional debut.

I was born in Nagpur in the state of Maharashtra, India and spent my first three years in Nagpur, Bangalore and Mumbai. When I was three years old, my father took a job in the United States and the family moved to the Hudson Valley, about an hour and half north of New York City. Not uncommon among immigrants to any country, we soon found an Indian community, attended traditional functions, and occasionally attended the local temple. I grew up listening to my mother-tongue – a dialect of Tamil – and would listen to my father play Hindi songs harkening back to his “good old days.”

My introduction to making music started with a family friend whose eldest son played the Indian classical violin. From him I learned the syllables (sa, re, ga, ma…etc.), strummed my first guitar and pressed my first piano key. I was five. Through one of my Amar Chitra Katha comics, I discovered the legendary Tansen, a jewel of vocal prowess in the court of the Mughal Emperor Akbar. My childhood imagination went wild with the idea that the human voice could bring the rains (Raga Megh) or set lamps ablaze (Raga Deepak). When I discovered that my parents had a recording of KL Saigal singing Raga Deepak, I listened to it obsessively but learned it cautiously so as not to spontaneously combust in mid-song.

Singing became ever present in my life. I would hum and sing to myself all the time which prompted my mother to enrol me in private voice lessons. Given there were no Indian classical voice teachers in Poughkeepsie, NY known to us at the time, she opted for a teacher of Western classical music. Her rationale that “music is music” set in motion my improbable path of a professional opera career.

I gravitated to Western classical music quickly and fervently once I started voice lessons. It is rare to find a teacher who can keep a child interested in anything for any amount of time. But I was fortunate to have a teacher who encouraged and challenged me musically, linguistically and vocally. I developed a specific interest in opera by the time I was ten years old and sang my first opera – the title role in Menotti’s Amahl and the Night Visitors – when I was 11. I discovered Mozart when my parents took my sister and me to the movie Amadeus, which I have watched over 250 times thereafter. I was hooked on Western classical music and opera was to be a part of my life through my embarrassingly slow vocal change, but one which allowed me to sing in almost every voice category.

Interestingly, the more I immersed myself in Western classical music, the more I closed myself off to Indian classical music. After singing an art song or an opera aria at a family gathering, I was invariably asked whether I knew any Indian classical songs to which I would reply that I didn’t. In retrospect, it is unfortunate that I hadn’t maintained my mother’s rationale that “music is music.”

As I was growing up, apart from my immediate family I always felt a disconnection between the Indian community – at least the Indian community in the Hudson Valley – and my pursuit of Western classical music. Perhaps if I had thought about it, I might have concluded that the disconnection, present within every ethnic group to some degree, may have been due to a host of factors: language, stylistic unfamiliarity, lack of exposure…etc. But as an adolescent, I hadn’t the capacity to consider those things and found solace in focusing on my path of musical study through college, graduate school and beyond.

Coming up as a young artist, I did not know of any peers on the opera circuit who were Indian. The process was a lonely one with respect to the support of countrymen, which I acutely felt when developing singers from other parts of the world would find their respective countries openly supporting, endorsing and embracing their successes. This created an additional sense of separation between me and my cultural roots.

In fact, it wasn’t until my return to singing after a seven year hiatus that I finally felt that the time was right to redefine my relationship with my culture, my personal history, my musical history and the Indian community. I have to give credit to my wife Gabriella for catalysing this change in outlook. Being the first person in her Costa Rican family to be born in the United States, we had much in common with regard to experience, but had enough differences to genuinely want to learn about each other’s cultures.

My return to opera took on an additional purpose: to open the operatic art form to a larger Indian audience. By sharing my path, my process, my dreams, my disappointments and my art with the audiences in theatres, online, in print or in live discussion, I find that the community gains a vested interest in not just the artist, but the art form as well.

The current opera season has given me some new and wonderful opportunities to perform my standard romantic operatic repertoire with new companies throughout the United States and Asia. But the opportunity to participate in the world premier of Ravi Shankar’s only opera, and to do so while debuting with the Royal Opera House and the London Philharmonic Orchestra, is truly special. This project has compelled me to revisit my earliest musical and cultural memories, to open myself to the artistic nuance of Indian classical music, to examine the legendary Ravi Shankar’s musical philosophy, to examine my own musical philosophy and to amalgamate myriad factors – apparent and latent – through the wonderful process of helping bring Sukanya to life.

Given my journey, it seems fitting that I would take part in a work which serves on many levels as an example of music’s universality, its ubiquity, its immutability. After all, music is music.