Rajendra Prasad Jain – A tribute

RP Jain – scholar, teacher, music lover, bon vivant – was one of the most civilised people I have ever known. I use “civilised” in the sense that Anton Chekhov described civilised people, as those who “respect human beings as individuals and are therefore always tolerant, gentle, courteous and amenable. …They have compassion for other people besides beggars and cats. Their hearts suffer the pain of what is hidden to the naked eye. …They are not devious, and they fear lies as they fear fire. …Civilized people don’t put on airs; they behave in the street as they would at home, they don’t show off to impress their juniors. They are not vain… They work at developing their aesthetic sensibility.” (in a letter to Nikolay Chekhov in March 1886, reprinted in Anton Chekhov, “A Life in Letters”, Penguin Classics)

All of these attributes were so absolutely present in RP. Despite his vast erudition and knowledge of matters musical, cultural and much else, he was gentle, modest and self-effacing. He had a sharp intellect and a wry sense of humour, disguised to some extent from those who did not know him well by his unfailing and almost old-world courtesy. His deeply generous nature was such that he gave unflinchingly of himself and his time. As a born pedagogue, he did not just teach as a profession – he delighted in sharing his passions, especially his passion for music, with others who had less knowledge or appreciation. Generations of people (young and old) benefited from this as he introduced them to the magical world of Western classical music.

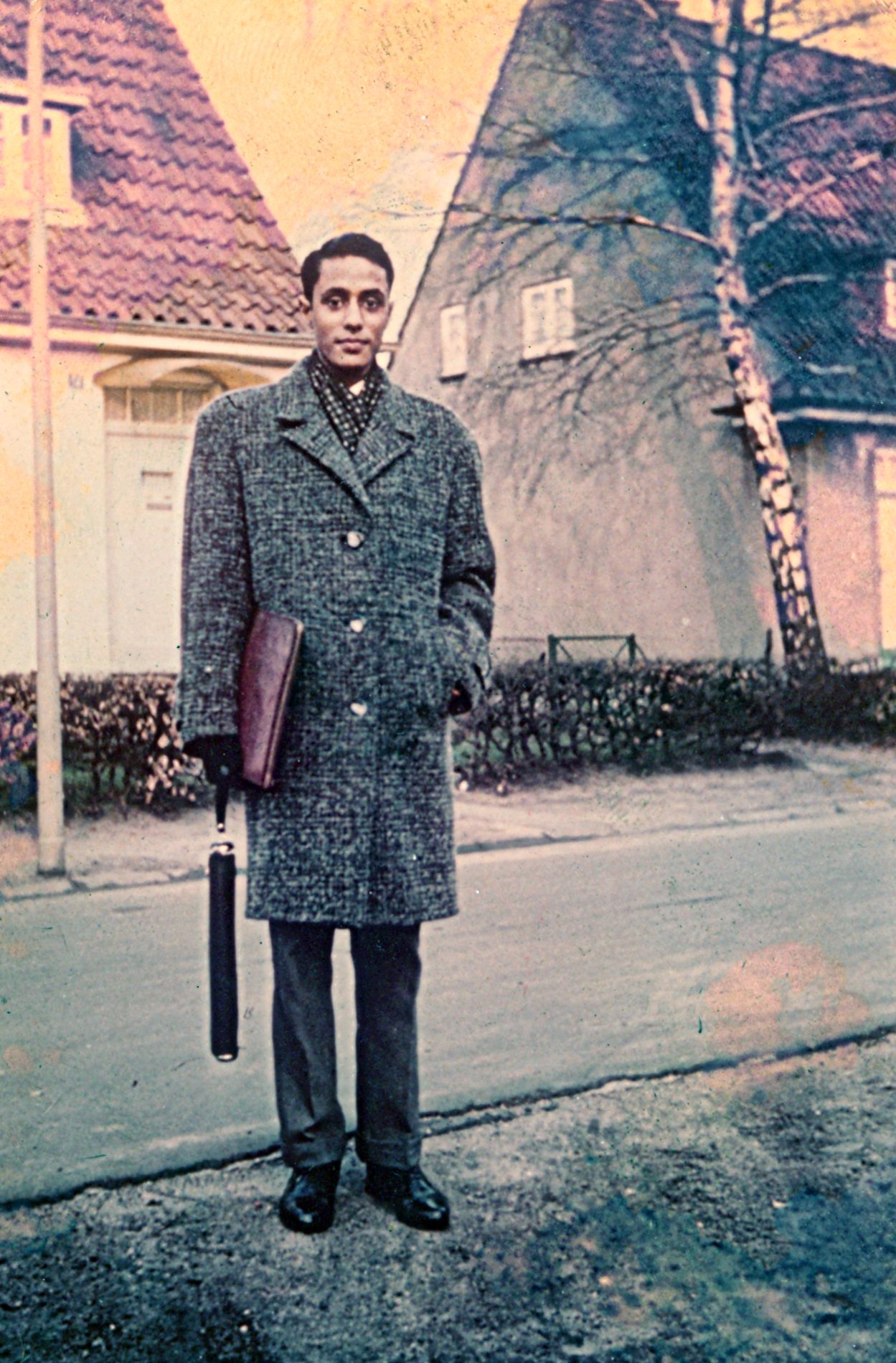

RP was born in Delhi on 10 March 1940, to a highly cultured family that valued knowledge, creativity and the arts. As a child he lived in Lahore until 1947, when his family moved to London where his father was posted, and where he studied in Haberdasher’s Askes’ School until 1954. On returning to Delhi, he completed his schooling from Delhi Public School and then joined St Stephens’ College to study History. He also did his MA in History from Delhi University, and then went to Germany to a PhD in Indology from the University of Hamburg. He returned to Indian in 1974 to teach at the Centre for German Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi in 1974, and continued to teach there until 1996, when he took up a position at the University of Muenster in Germany. He finally returned to Delhi in 2005, when he was officially retired but continued to be very active in all sorts of ways.

Throughout his life, Western classical music played an enormous role. His early interest in it was further refined and developed through the exposure he got in his travels and his own enthusiastic efforts. He built up an enormous and very impressive collection of recorded music – first long-playing records, then cassettes and then CDs and VCDs. He had many different versions of the operas, ballets and symphonies that he particularly liked. Over the years, he shared the joy of all this music with others: in little group sessions of aficionados at his home; at the Max Mueller Bhavan Library where the series “Impromptu” was organised for the interested public with monthly lectures on particular composers; at other venues like “The Attic” and later at the India International Centre where his summer series of showings of operas and concerts became a beloved and much-awaited sets of evenings that helped to lessen the burdens of a North India summer.

What made all these so special was not simply RP’s vast musical knowledge and exceptionally fine ear, but the sheer exuberance of his love for music that inevitably infected his audience. For this understated and modest person could be passionate and full of vigour when discussing the intricacies of particular pieces of music, or tracing the socio-political context of some compositions, or dwelling on the merits of favoured performers. He had an acute understanding that often revealed what could be hidden glories in music, and could change your understanding and appreciation with his insights. I still remember how he brought to my attention the sharp social analysis embedded in some of the music of Prokofiev and the emotional complexity of later Verdi compositions, as well as how utterly passionate much of Bach’s music is. He failed to ignite in me his enthusiasm for Wagner, but just watching him listen to it was often enough to make me realise that I was missing something big by not getting it in the same way that he could!

He showed the same fervour in his very committed voluntary work with the Delhi Music Society, where he headed the Programmes Committee and organised many concerts in his later years. As his colleagues in the Music Society, we all grew to recognise and rely on his calmness and the sense of Zen-like tranquillity he brought to what were often heated meetings. And when he did get aroused, he was always utterly gentlemanly in his responses and dealings, and always appreciative of and generous to others. It will be hard to imagine the Delhi Music Society without him, just as it will be hard to imagine all the best features of cultural life in Delhi without his utterly civilised presence. Those of us fortunate enough to have had our lives enriched by him continue to carry that richness inside us.