Our Immanuel Master

“Do you not know that a man is not dead while his name is still spoken?” – Terry Pratchett

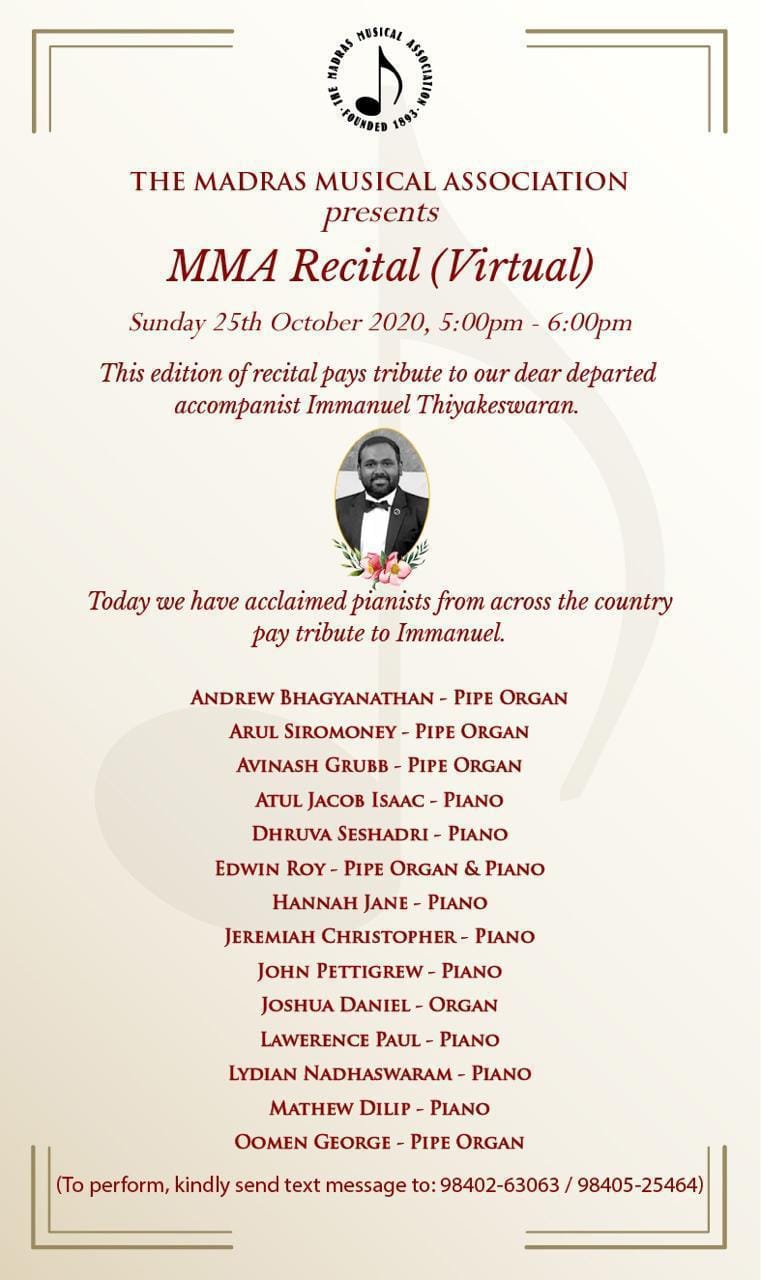

On October 5, 2020, a horrific car accident on the highway at night spirited away the lives of Immanuel Thiyakeswaran and his parents. Immanuel was a musician brimming with accomplishments, accolades, and much that he was yet to display to the world. His name may not resonate with the public at large but it would have had he lived longer. He was only 25.

It was eerily reminiscent of the death of Kerala’s renowned violin virtuoso Balabhaskar, who also perished in a car accident at night two years ago almost to the day.

Immanuel’s funeral service was held at St. Andrew’s Church (“The Kirk”) in Chennai where he had served as pianist and organist for services. In his eulogy, Augustine Paul, Music Director of the Madras Musical Association (MMA) described him as “young shoulders which carried a wise and mature head.” Paul added:

“He never worked for money. He worked for the music, and the money kept coming in. He never asked for money, but people gave. He never fixed rates, but people paid him with a happy heart. That’s how he lived. He enjoyed what he did.”

In addition to being a performer, Immanuel excelled a role usually deemed by the world as secondary — the role of an accompanist to soloists and choirs, a role he chose of his own accord. He was also a music teacher much beloved to his students. What follows is a pen-portrait of “Immanuel Master” as seen through the reminiscences of two students — Lydian Nadhaswaram and Amirthavarshini.

Lydian Nadhaswaram is a multi-instrumentalist but he is most well known for his prowess on the piano, especially after he won The World’s Best, the talent show organised by the American television station CBS. However, he started out as a drummer at age 23 months.

Percussion was his first love, but Lydian was also fascinated by the keyboard. His father, music director Sathish Varshan, taught him some of the basics, and showed him a YouTube video of the Hong Kong piano prodigy Tsung Tsung. Eight-year-old Lydian thought: If he plays the piano so well at so young an age, so can I. And the desire took root. His sister Amirthavarshini had already started learning piano. The hunt for a piano teacher began. One of Varshan’s musician friends passed on a glowing recommendation of his fellow musician and childhood friend Immanuel. Varshan made an appointment.

“Oh my God, he was awesome,” said Lydian, recollecting his first meeting with Immanuel Master.

“Place any music in front of him and he played it right away, no matter how tough. We were so impressed with what we heard and saw that we enrolled as his students on the spot. My sister and I learnt piano from him, and my sister learnt music theory as well.”

Immanuel Thiyakeswaran on the piano as a teenager (recorded in 2011)

Then they heard from other sources that Immanuel was a man of few words.

“We were a little concerned whether he could instruct classes properly. But he was an excellent teacher. He may have been mostly silent in public, but he wasn’t like that at all in the classroom. I’ll never forget the way he initiated and led classes and made the task of learning easy for us. We were so comfortable studying under him. He was my first piano teacher. He taught me how to sight-read, how to let the music flow from my fingers in a smooth way. Everything grew out of that.”

At the time, Varshan was composing music for the Tamil feature film Purampokku Engira Podhuvudamai, and Immanuel came to their house to help out with a music sequence. Varshan had just bought an upright piano for his children, their first, and requested Immanuel to check it out. Immanuel obliged, playing Mozart’s Rondo Alla Turca (Turkish March), which Varshan videotaped. At that time Lydian still attended regular school (he is home-schooled now) and when he returned home, Varshan played it for him. Lydian was all eyes and all ears.

Immanuel Thiyakeswaran plays Mozart’s Rondo Alla Turca (“Turkish March”)

As Lydian was naturally endowed with perfect pitch, he learnt the piece by ear. He played it when he met Immanuel Master next, and was rewarded with his teacher’s broadest smile.

Mozart’s Turkish March has a sentimental place in Lydian’s heart; it was the first piano piece that he learnt and it is associated with his first piano teacher who he holds in the highest esteem. He played it in his march towards winning The World’s Best, and again when invited to participate on The Ellen Show.

Immanuel Master was impressed with Lydian’s prodigious talent as he navigated his young student through the art and craft of mastering the piano. Within six months his teacher decided that Lydian should take the examinations of the Trinity College London. (Two British institutions, Trinity College and the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music [ABRSM] recognize teachers and institutions in other countries who can train students. Examiners from Britain periodically visit and conduct examinations.) Immanuel Master made a momentous decision: to send Lydian directly for the Grade 5 examination, skipping Grades 1 to 4. Immanuel felt that with Lydian’s command of the piano he could even pass a higher grade, but because Lydian had never taken a piano examination before, Immanuel settled on the Grade 5 exam as the best option. He coached Lydian intensively on the pieces on which he would be examined.

Three months after the exam, Immanuel phoned. Lydian’s mother Jhansi Varshan answered, only to hear this: “Ma’am, the marks have come, and regarding Lydian’s performance, I’m so sorry, very sorry, but I really don’t know how to break this news,” — and as her heart sank, he continued — “but Lydian has been awarded a Distinction.”

Not only was Jhansi’s relief palpable, but the family learnt something they had not known: their ever-so-serious Immanuel Master had a hidden sense of humour.

“All credit for my success in this examination goes to Immanuel Master.” Lydian pointed out that Immanuel anticipated what the examiners would look for. “He taught me each and every dynamic. He sharpened my sight-reading. I’m so grateful.”

Immanuel Master had mammoth music skills, but what was his non-music skill that most stood out?

“Patience,” Lydian answered without hesitation.

“He was serious and strict but at the same time, friendly, something I admire. No matter what mistakes his students made, he never got angry, remained calm, and never stopped smiling.”

Immanuel Master usually scheduled a separate class for Lydian and Amirthavarshini but at times they were part of his group classes. The classroom was divided into several sections: piano, keyboard, music theory, sound engineering, and so on, with students at each station.

“He would give me very thorough instruction, then give an exercise, and then go to the next student, and the next,” Lydian recalled.

“When he came back to me, he would check how I had done. When I made mistakes, he was so patient, telling me in Tamil: Parava-illai (No problem / Don’t fret over it), which was so sweet of him. He would have me repeat the exercise, or move to the next step if he was satisfied with my playing. When I did well, he appreciated it with smiles. He was very organized, and made sure he gave equal time and attention to every student. These are qualities I admired in him as a teacher.”

In course of time, Immanuel Master suggested that Lydian enrol as a student under Augustine Paul. Paul, Music Director of the Madras Musical Association (MMA), was arguably the most sought-after teacher of Western classical music in Chennai. In fact, Immanuel Master was Paul’s student too. And so Lydian followed his teacher’s suggestion. But he thinks Immanuel Master was a tad self-deprecating: “There are things that Augustine Sir taught me that could have been just as well been taught by Immanuel Master.”

Augustine Paul decided to send Lydian for Trinity’s Grade 8 piano examination, skipping Grades 6 and 7.

“Whenever I met Immanuel Master at Augustine Uncle’s classes, which were group classes, Immanuel Master would take me aside and make me play my examination pieces, correct any wrong notes, and improve my sight-reading. On the two or three days before the exam, he spent a lot of time with me, thoroughly coaching me.”

Most students taking the exam are of college-going age if not older. But not only did young Lydian ace the exam earning the Advanced Certificate in Piano with Distinction, he also stood first in India. And he made his teachers and family proud by sweeping multiple awards: the Cicely Goschen Shield, the Amy De Rozario Cup, the P.P. John Memorial Prize, and the Rajagopal Menon Prize.

But this was just a prelude to the big event: winning The World’s Best. On the day he returned to Chennai after his victory, Lydian had a scheduled class with Augustine Paul, and he took his trophy along. As noted earlier, Paul always held group classes and Immanuel Master was also his student. It so happened that Immanuel Master stepped out of the classroom just as Lydian entered the building. Knowing that Lydian was not one to skip classes continuously for a month, he asked, “Where were you all this time? And what’s that in your hand?”

When Lydian explained, the visibly overjoyed Immanuel Master promptly posed with Lydian and the trophy for a photograph. When Lydian had first come to him, sheet music was a page covered with peculiar squiggles. He did not know what Major and Minor stood for. Immanuel had taught him piano from scratch. And now, Lydian had conquered America and the world, besting the crème de la crème of arts and entertainment from countries around the globe. What a proud moment for a teacher, indeed.

But there was a catch. The World’s Best was not live action. It had been recorded over a month, and CBS was to air the episodes over a season. So this was classified information. Immanuel Master nodded, and his twinkling eyes seemed to say: Trust me. Don’t you know that I’m the silent type? Nevertheless, Immanuel Master made a few video calls to his circle of close friends who also knew Lydian, swore them to secrecy and spread the joy.

“Immanuel Master was my teacher but I also think of him as a dear friend,” Lydian said,

“He was in the orchestra of the MMA, and so was my sister, and so whenever I attended an MMA concert, we met and talked music. He always stayed in touch. Many times, when I posted a YouTube video, he responded, appreciating what I did well and pointing out any shortcomings that he spotted. He never stopped being my teacher.”

Amirthavarshini started in music on vocals and piano, then moved on from the piano to the flute. She studied piano under many teachers, of which Immanuel Master was the last. While his student, she discovered that he was the accompanist that every musician craved for. When she had sufficiently mastered the key flute to give public performances, she asked him whether he would be willing to accompany her. He said “Yes” without a second thought. They performed together as soloist and accompanist in concert after concert. Then she became Augustine Paul’s student for vocal lessons, and as Immanuel Master used to accompany most of Paul’s students, the relationship continued.

“The role of an accompanist is quite important because it really enhances your performance,” Amirthavarshini highlighted a generally underrated role.

“Immanuel Master sight-read the music of all my pieces as though he had been playing them for years. Instruments like violin and viola only have single-line notations but for the piano, you simultaneously read the left and right scores while playing with both hands. But even his first playing of a piece sounded so elegant, so professional. There were no mistakes — none. I have never known anybody, anybody, who could sight-read like he did.”

Amirthavarshini noted that Augustine Paul, in his eulogy at Immanuel Master’s funeral service, pointed out that Immanuel never needed anybody to stand beside him and turn the pages of sheet music while he played a long piano piece. His sight-reading dexterity permitted him to turn each page well ahead of time.

“Immanuel Master and I played in the MMA Orchestra together,” Amirthavarshini continued.

“He would play piano, viola, violin, and many other instruments. He not only accompanied me in all my concerts, but also in all my Trinity and ABRSM flute and vocal exams, as well as the High Scorer concerts (concerts held as a result of the high marks obtained in the examinations). So I had a great experience performing with him.”

Not just the candidates who took the music exams appreciated Immanuel, examiners did so too. This tribute came in from Christopher Horner, an international examiner for Trinity College:

“I am greatly saddened by this news. Immanuel Thiyakeswaran really stood out amongst the pianists who accompanied exams for Trinity College London for whom I work as an examiner. A visit to Chennai always meant that candidates not only had someone who knew their pieces or songs but perhaps, even more important, a calming and positive presence which would help the best possible outcome in the exam. His loss to you all and music where he worked is immeasurable. My deepest condolences to you all and on behalf of Trinity College London.”

Amirthavarshini said,

“Although his primary instrument was the piano and he also was at home with the violin and viola, he also played other instruments like the mandolin and the guitar and many stringed instruments. We would go to his studio before our exams for our practice sessions, and sometimes his friends would come over at that time for a jam session…”

Thus Amirthavarshini and Lydian discovered that their Immanuel Master played at least, if not more, five or six musical instruments. They learnt that Immanuel Master was also a composer, especially in gospel music and church music. Many times, when the lessons were over, they would have informal but weighty discussions about music. Those were the days.

In his eulogy, Augustine Paul also emphasized that Immanuel had chosen to take on the role of an accompanist fully aware that he would have no choice in selecting the music — he would have to play whatever the soloist or choir wanted. And yet, Paul remarked, Immanuel really enjoyed what he did. He would adapt the score to fit each performer. The role of the accompanist often seems thankless — the audience appreciates the soloist, the choir, the conductor, but almost never the accompanist. But, as Amirthavarshini pointed out, the accompanist’s role is more central than the audience realizes.

On this issue, Lydian highlighted the esteem and affection for Immanuel Master by Chennai’s Western classic musical community. “Immanuel Master had a special value for everybody. Generally, performers won’t put their accompanist’s name on the programme sheets, but Immanuel Master’s name was included in every programme card whenever he accompanied anybody. Even if he had never seen the score he was to play as accompanist before, he played it just like that.” Lydian snapped his fingers to illustrate, and finished, “He was really special for everyone.”

“He’ll continue to inspire us like anything,” Amirthavarshini said,

“His dedication to practice, not resting on his achievements but always striving for excellence, his ability to sight-read….he was so young, and achieved a lot. It’s like that saying: ‘Practice makes a man perfect,’ and he was perfect in all that he took up. Even if we can’t be like him, we would like to try to be like him.”

The philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti wrote: “Tell your friend that in his death, a part of you dies and goes with him. Wherever he goes, you also go. He will not be alone.” A part of a great many people who knew and were touched by Immanuel Thiyakeswaran have accompanied him on his final journey. He and they are forever united by the sound of music.