AN INVALUABLE LEGACY

This year, as the NCPA turns 50, we take a look at how a dream became a thriving reality. By Anil Dharker

“One day, perhaps, the NCPA’s work may be more important for the country than the work of the steel company.”

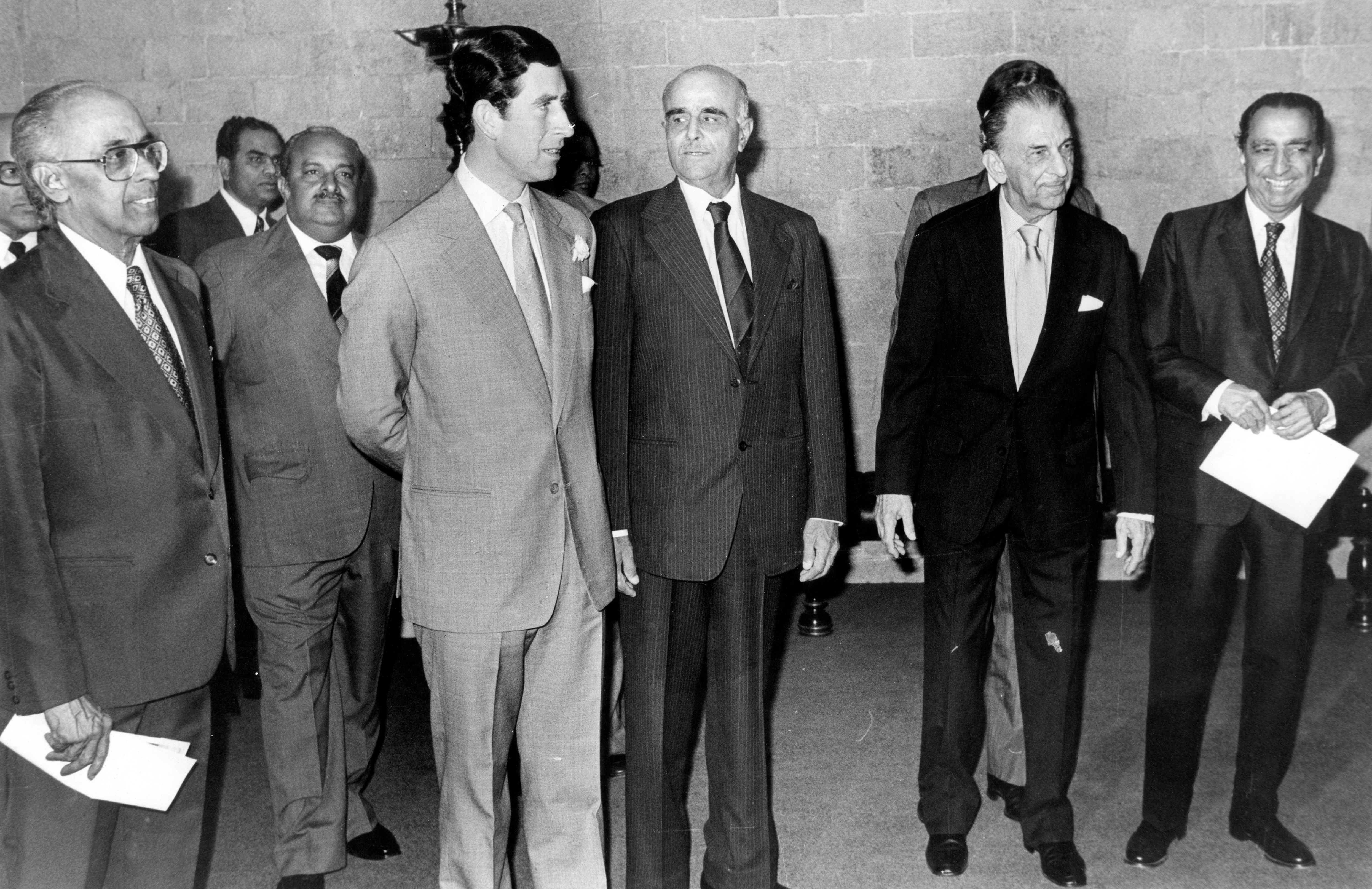

These were JRD Tata’s words to Jamshed Bhabha when the latter apologised for taking up so much of Tata’s time for the founding of the NCPA, and distracting him from important Tata Steel matters. Fifty years on, has that day come? Probably not, and the day may possibly never come, but when you think of it, there can never be competition between the manufacturing of essential goods and the promotion of culture; in fact, the two complement each other in a meaningful way in any civilised country.

Do they do so in India? Ours must be one of the most hypocritical societies anywhere: we declaim about our culture and heritage from every available rooftop, but do nothing to preserve them. I remember a photograph which said it all: in the middle of a field somewhere was an old sculpture, obviously an antiquity. Tethered to it by a rope was the farmer’s cow, while he went about planting some saplings. That, of course, doesn’t mean there is total neglect: our state and national museums and bodies like the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) are doing what they can, but it’s not nearly enough because their budgetary allocations are so very inadequate.

Humble beginnings

This is even more so with our performing arts. Music is the source from which all the arts grow; it is the one art which comes naturally to most living things, and it certainly does so with human beings. Our tradition of classical music, both Hindustani and Carnatic, goes back centuries, and as is so with musical traditions elsewhere, it is closely linked to religion (note how Saraswati, the goddess of learning, is always shown with a veena). In the course of these centuries, music has grown, flourished and refined through the oral tradition of guru-shishya parampara. This tradition survived through the patronage of maharajas and other ruling princes, but once privy purses and royal titles were abolished, what would happen then?

That is the primary reason for the formation of the NCPA fifty years ago in 1969. I do not know how many of you remember, but ‘National Centre for the Performing Arts’ seemed too grand a name for something which was so very tiny: the NCPA’s first home was not the grand cultural complex at Nariman Point we go to now, but a small space in Akash Ganga building on Bhulabhai Desai Road. The building is still there at Number 89.

I had just come back from London in the 1970s, and looking for culture, found my way to the NCPA’s auditorium with 100 seats. That makes it even smaller than our Little Theatre. Small though it was, it had been acoustically treated so that music and dance programmes could be held there regularly. This was a long time ago, so don’t rush to correct any lapses in my memory, but even art films, poetry recitals and plays were held there. Next to it were small dance and music practice rooms, and even a Reading and Listening Library. If there is a will, you can manage without vast spaces.

A grand vision

If Bhabha was the prime mover with JRD Tata by his side, you can assume that the small space was only a prelude to a grand vision. So an approach was made to the Maharashtra government for land to set up the NCPA, a national centre for the preservation and propagation of our performing arts – and indeed of all arts as the original mission statement and charter clearly states. The state ministry was helpful, no doubt because the NCPA had the firm backing of India’s then Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi. “We will give you land here,” the Maharashtra government said, demarcating a generous parcel of land in – guess where – the vicinity of the Ajanta Caves.

That, obviously, was not a workable proposition, but the question remained, where do you find five acres of vacant land in the centre of a city as busy and overcrowded as Mumbai? Bhabha cast his eye on the sea. Why not reclaim land from it? The government agreed. The first venue was to be off Marine Drive, opposite Taraporewalla Aquarium. For various reasons that was dropped in favour of where the NCPA stands now. Eight acres were reclaimed and work began on laying the foundation of the National Centre for Performing Arts.

The first permanent building was the Teaching and Research Block which then consisted of the Little Theatre, recording studios, master classrooms, an archival vault, a reading and listening library, a dance academy, an art gallery, a research laboratory and executive offices. Some of these may have changed over the years, taking on different forms, but what is astonishing to learn is that the Little Theatre was primarily designed as a recording studio with the requisite level of acoustics. Why a theatre with seats then? Because Indian musicians are used to performing before an audience; put them into a studio with only recording equipment for company and they would freeze. The NCPA recorded most of our finest musicians, and its archives contain priceless tapes of a roll-call of the ‘Greats’. The list is really long and worthy of the NCPA’s primary aim of preserving our outstanding classical performers. These recordings are preserved in the best possible conditions of temperature and humidity.

As good as it gets

The Tata Theatre was inaugurated by Indira Gandhi on 11th October, 1980, and this 1040-seater auditorium remains till today the nearest to acoustic perfection as any venue in India. Although the use of amplification is now the norm, acoustic consultant Cyril Harris and architect Philip Johnson collaborated in making a large auditorium into an intimate space requiring no amplification, and where the theatre’s fan-shape was designed to bring the audience as close to the performer as possible.

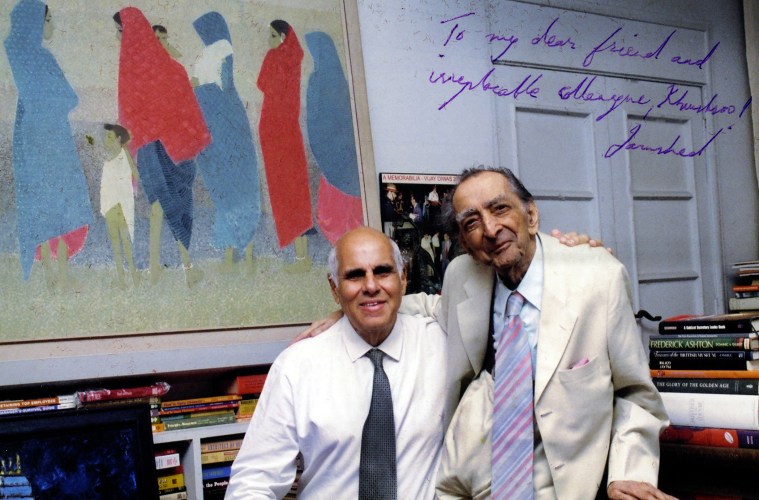

The construction of the Experimental Theatre which gives complete flexibility in staging and seating, the Godrej Dance Theatre and the Jamshed Bhabha Theatre (JBT), each one has a story worth telling at length, especially JBT. How many NCPA members are aware that when the under-construction theatre was almost complete, a fire engulfed it in the middle of the night and burned it to the ground? As he watched his dream go up literally in smoke, Bhabha said, “There will be no enquiry and no recriminations. We meet tomorrow morning and start anew.” Not many know too that Bhabha wanted to call it the National Theatre, but it was Khushroo Suntook’s insistence that made Bhabha relent to it being named after himself. It is a fitting tribute to a man without whose vision and dedication (not to speak of his bequest of everything he possessed), the NCPA would never have come into being.

Remarkably, Bhabha found as a successor, a man who is equally dedicated, equally persistent and also has a grand vision. Here it is pertinent to quote Bhabha, “The long-term Master Plan for NCPA drafted by me in 1966 may seem much too ambitious and big, requiring for its full realisation hundreds of crores of rupees, but in planning a pioneering institution, it seems to me to be better to ‘Think Big’ and ‘Start Small’, rather than ‘Think Small’ and ‘Start Small’, and then grow in haphazard fashion.”

Khushroo Suntook’s vision has brought to life the Symphony Orchestra of India (SOI), not only delighting us but now also finding recognition outside the country. Simultaneously, Indian classical music and dance forms have been brought centre stage. Critics (and aren’t there always some who will carp?) complain of a bias towards Western classical music, but this is probably because the SOI is so high-profile. An analysis shows that Western music takes up only 14% of the total NCPA programming. Who can grudge that? A by-product of the SOI is often overlooked by critics – this is the school of music for children, which is preparing a future generation of first-class musicians.

Theatre is the new frontier being tackled. Directors and technical experts have been brought in from London’s National Theatre to work with Indian actors and surely this will have a ripple effect on theatre in general. A repertory company should ideally be the next step.

There is more, but we should leave things to unfold and catch us by surprise, shouldn’t we? The National Centre for Performing Arts is now 50 years old, and while we celebrate its achievements, we know more applause and many more standing ovations are reserved for the future.

This piece was originally published by the National Centre for the Performing Arts, Mumbai, in the January 2019 issue of ON Stage – their monthly arts magazine.