Famous Composers as Subjects of Opera

Recently, I had a chat with a young colleague who suggested that the writing of biographies of great composers was a boring myth-making exercise practiced in a cultural galaxy far away and two centuries removed. She had a point about the myth making, of course, but I really couldn’t see how it was all so boring. Mozart was supposedly poisoned by Salieri, Schubert died of Syphilis, which he picked up who knows where, Paganini practiced witchcraft, Chopin smoked opium, and Gesualdo killed his wife Maria d’Avalos and her lover Don Fabrizio Carafa before going completely off the deep end.

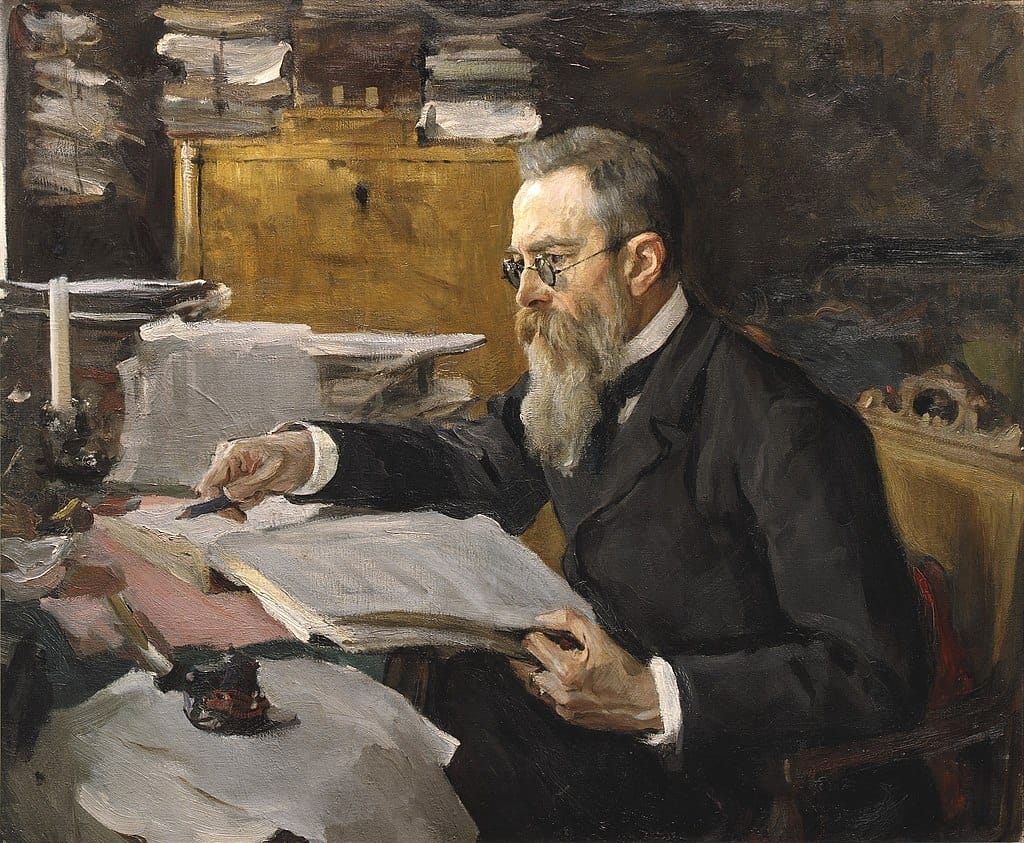

This is not simply biography—invented and embellished as it may be—it’s the stuff of opera. So I started to search for operatic settings based on biographical aspects of famous composers, and I was surprised how plentiful my search turned out to be. The circumstances of Mozart’s early death have always been of special interest, with particular attention paid to his relationship to the court music director Antonio Salieri (1750-1825). Salieri was blamed for numerous intrigues designed to ruin Mozart’s reputation and sometimes even assigned responsibility for his early death. That relationship between the two inspired a number of literary elaborations, where characters and events were depicted with great freedom. Alexander Pushkin (1799-1837), widely considered the greatest Russian poet and founder of Russian literature, wrote his verse drama entitled Mozart and Salieri in 1830. And Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908) turned it into a one-act opera in two scenes of the same name in 1897.

For Pushkin and Rimsky-Korsakov, the character of Salieri enjoys a high social position as a composer. However, he is secretly jealous of Mozart’s work because he recognizes their superior quality, and disapproves of Mozart’s vulgar character. So he decides to invite Mozart to dinner and plans to poison him. As they are dining, Mozart is troubled by his work on his Requiem, commissioned by a mysterious stranger. He declares that genius and criminality are surely incompatible, which prompts Salieri to pour poison into Mozart’s wine. Mozart drinks and starts to play at the keyboard, and Salieri begins to cry. Overcome by the poison, Mozart leaves and Salieri ponders once more Mozart’s belief that genius could not commit murder.

Rimsky-Korsakov incorporated quotations from Mozart’s Requiem and from Don Giovanni into the score, while Albert Lortzing (1801-1851) exclusively draws on Mozart’s music in his 1832/1833 vaudeville Scenes from Mozart’s life. Lortzing arranged popular numbers from Mozart operas and singspiels, and also included instrumental compositions and the Requiem. At times he combines different compositions to form a single number, and clearly abbreviates others. And since we are talking about a vaudeville production, the music is accompanied by much interpretive gymnastics.

When Lortzing composed his singspiel in 1833, rumors that Salieri had poisoned Mozart had started to percolate, but they were almost immediately refuted. For Lortzing, the difference between Salieri and Mozart lay less in their supposed characters and social standings, but in the opposition between Italian and German music. In the first part, high-strung singers at a sumptuous banquet in the Prater surround Salieri, while Mozart is shown in his home setting with family and friends. Lortzing was eager to promote the idea that Mozart only lived for his art, and that he was always concerned for the welfare of those around him. During a feast in the last part of the singspiel, Mozart receives the late recognition of the emperor and is appointed to a conductor post. Franz von Suppé (1819-1895) was both the originator of Viennese Operetta, and a busy composer in a subgenre entitled “Artist’s Life Portrait.” His biographical take on Mozart featured a theatrical play written by Leonhard Wohlmuth, which was described as “harmlessly good-natured, with the character of Mozart seen as a sentimental and babbling fool.” Suppé’s contribution to the score and his use of numerous Mozartian melodies was seen as “proving a certain proficiency of compositions, which nevertheless has nothing to do with creative genius. That the overture to Mozart has been performed for a long time, while all other numbers are forgotten, is not Suppé’s, but Mozart’s merit.”

If you are looking for a “wildly inaccurate account of the life of Frédéric Chopin,” look no further than the four-act opera Chopin by Giacomo Orefice (1865–1922). With a libretto by Angiolo Orvieto, Chopin premiered in Milan in 1901 to mixed reviews. The Musical Times reported, “This rather curious lyrical stage-work was a distinct success.” Critics in Paris were less kind, commenting, “It is an idea, perhaps ingenious but certainly bizarre, to create an opera score by borrowing the elements of various works by a genius who, throughout his life, never dreamt of writing for the theatre.” In the end, Orefice was accused of having committed “a sacrilege.” The overture is based on Chopin’s Fantasy on Polish Airs, and Act 1 set in a village in Poland at Christmas time.

Chopin declares his love to the fictional Stella, and once in Paris, Chopin’s new love Flora witnesses Chopin compose a nocturne inspired by the struggles of Polish people. Act III is set in Majorca, where the real Chopin spent the winter of 1838-9 with George Sand. In the operatic version Chopin is there with Flora and their daughter, who dies after a thunderstorm and is mourned by the local population. Finally, in Act IV Stella arrives in Paris from Poland just in time for Chopin to expire in her arms. Orefice freely borrowed from Chopin’s music, including sonatas, polonaises, mazurkas and nocturnes, and “modern assessment suggests that Chopin is “in essence a kitsch contribution to the last vestiges of late 19th-century romanticized bohemianism.” That may also be the case, but boring it certainly is not.

By Georg Predota. Republished with permission from Interlude, Hong Kong.