European History Through the Lens of Classical Music

The Symphony Orchestra of India, resident at the NCPA in Mumbai, is blessed with the harmony in diversity of many nationalities among its musicians. The unique sound of this young-in-years, musically maturing ensemble reflects not only the virtuosity of the players but also their international cultural contexts and training pedigrees.

The opening concert of the Autumn 2023 Season, under the baton of Richard Farnes on 10th September, featured three works that span the evolution of European classical music as well as European history from the first quarter of the 19th century to the turbulent wartime period of the 1940s.

Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868): Overture to Semiramide

The concert opened with Italian composer Gioachino Rossini’s overture to his exquisite bel canto opera, Semiramide. His music evolved in harmony with the shifting tides of European history during the 19th century and contributed significantly to the cultural tapestry of his time—initially through his music and later through his culinary exploits. After his relatively early retirement from the musical world before he turned 40, he conjured up gourmet recipes like Tournedos Rossini, perhaps as much a labour of love in its preparation as his great operas.

While his early compositions resonated with the optimism and revolutionary spirit of post-Napoleonic Europe, Rossini’s style adapted to the changing times of political turmoil and the rise of European nation-states with their individual cultural and musical voices. His later works, like Guillaume Tell, showed a more mature and introspective musical language, reflecting the introspection of the Romantic era. Rossini’s contemporaries included poets Shelley, Keats and Byron. Shelley and Rossini were both born in 1792, but Shelley’s epitaph had already been written around the time that Semiramide was premiered in 1823.

As nationalism and historical consciousness grew, Rossini’s music began to incorporate elements from various European folk traditions, aligning itself with the broader trends of the 19th century. Semiramide mirrors the era’s fascination with the exotic and oriental, which grew as European maritime powers began to extend colonial influences into distant lands.

Set in Babylon “somewhere in antiquity”, the libretto by Gaetano Rossi based on Voltaire’s 1748 tragedy recounts the story of the legendary Assyrian queen Semiramis. After having her husband Nino poisoned, she rules the Babylonian Empire, and fancies a stranger, Arsace, over her leading suitor, Assur. Arsace, however, discovers that he is in fact Ninias, the son, presumed dead, of Semiramis and Nino. Assur tries to eliminate his rival; Semiramis tries to save her son but is mortally wounded by him in a scuffle. Arsace thereby avenges his father’s death.

Semiramide has its own overture, which was almost certainly composed last after all the arias and orchestral sections of the opera. Unlike many operatic overtures of the day, especially those of Antonio Salieri who wrote his opera overtures as sinfonias, it borrowed musical ideas from the opera itself, thus making it unsuitable for use with another score. A hushed, rhythmic opening suggestive of a build up to the events of the opera is followed by the andantino for four horns taken from a vocal quartet towards the end of the first act in the opera, ‘Serena e vaghi rai’, set in the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. The main (allegro) portion of the overture draws upon the opera’s final scene.

Plenty of contrast between pianissimo and fortissimo phrases, pizzicato countermelodies in the strings and finally a lively allegro with martial overtones rising to a “Rossini crescendo”, the overture to Semiramide is a delight to perform, to watch and to listen. The overture is an enthralling representation of the time’s musical tastes, combining intricate orchestration and bold harmonies.

Aram Khachaturian (1903-1978): Concerto for violin and orchestra in D Minor

Having lived the entire span of his life in the 20th century, Aram Khachaturian’s Armenian ancestry and Georgian upbringing blended well with his Sovietera musical career, the USSR having taken over both Armenia and Georgia by 1922. In his own words, “I grew up in an atmosphere rich in folk music: popular festivities, rites, joyous and sad events in the life of the people always accompanied by music, vivid tunes of Armenian, Azerbaijani and Georgian songs and dances performed by ashugs (folk bards) … became deeply engraved on my memory.” Formally trained in cello and composition, he was also a sensitive pianist as reflected in his Children’s Album compositions.

Khachaturian served as the Deputy Chairman of the Organization Committee of the Union of Composers from 1939 to 1948. It is during this period that he composed the violin concerto, and donated his 1941 Stalin Prize money to the State with a request to use it for building a tank for the Red Army.

The Violin Concerto, originally composed in 1940 for Ukrainian violinist David Oistrakh, was performed at this concert by soloist Marat Bisengaliev, who carries the sterling musical tradition of Oistrakh through his teacher Valery Klimov who in turn studied with Oistrakh.

The first movement is curiously marked as allegro con fermezza (firmly cheerful)—a movement marking not seen before or since as far as I could ascertain. Khachaturian’s original cadenza for the first movement is nearly six minutes long; Bisengaliev elected to play the shorter Oistrakh cadenza which nonetheless captures the Armenian folk melody spirit of the movement. But it is the slow movement, andante sostenuto, that many consider to be the heart and soul of the concerto. Deeply contemplative and almost funereal in its dark, brooding yet elegiac melodies and disquieting harmonies, it borrows one of its themes from a funeral song from the film Zangezur for which Khachaturian composed the score in 1938. Bisengaliev’s final sustained A flat remained at odds with the orchestra’s chillingly implacable A minor descent. Khachaturian, like many artistes of his generation, would have fallen under the shadow of the Second World War which eventually consumed much of Europe and the USSR, and the sense of tension, foreboding and grief in this movement can be thought of as an artistic response to turmoil. Yet there is hope; a brilliant fanfare opens the final allegro vivace. This folk-influenced movement is especially infused with elements of Armenian folk music, featuring distinctive rhythms, melodies and modes that evoke the rich cultural heritage of the region.

Khachaturian’s Violin Concerto, therefore, masterfully ALAMY intertwines the cultural richness of his homeland with the broader anxieties of a world on the brink of war. It serves as a testament to the power of music to encapsulate complex emotions, telling a story that transcends borders and resonates with audiences worldwide.

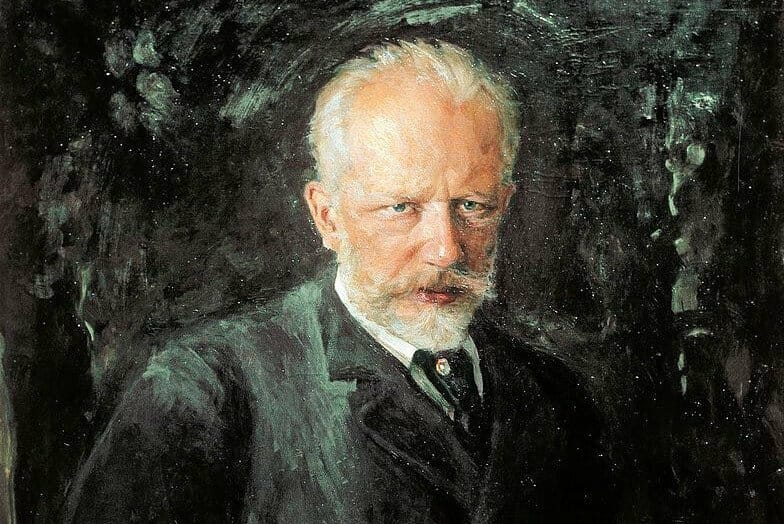

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893): Symphony No. 6 in B Minor, “Pathétique”

The Russian composer’s symphony is called “Pathétique” (French for ‘arousing emotion’) perhaps because he died just nine days after its premiere in the winter of 1893, and many feel that the largely dark, brooding, nature of the work reflected Tchaikovsky’s own emotional state at the time. At least one theory— not necessarily the most credible one—suggests that he committed slow suicide by the deliberate act of drinking un-boiled water during the prevalent cholera epidemic.

Unarguably Tchaikovsky’s most emotionally charged work, the symphony serves as a profound reflection of the composer’s inner turmoil and the sociopolitical climate of its times. This was a period of great change and upheaval in Russia, characterised by political unrest and the push for social reforms. The growing discontent among the masses is echoed in the symphony’s dark and brooding atmosphere that creates a sense of disillusionment and unease.

Musically, this is a towering composition of its time. It builds on Tchaikovsky’s mastery of melody and layers it with complicated harmonies that we have come to associate with the emotional complexity—deeply yearning, richly textured—of the late Romantic period. Right from the slow adagio with a simple motif that builds up as the first theme of the opening movement into the exquisite second theme of the first movement. In the dance-like second movement, allegro con grazia, unique in its rarely used 5/4 meter—sort of like a waltz with a missed beat—the composer offers us a fleeting glimpse of happiness amidst tragedy, like the philosophical aphorism that there is no happiness; only moments of happiness.

The allegro molto vivace begins much like the early Romantic scherzo, a sense of strings and woodwinds chasing each other, periodically interrupted with a bold marching pattern that eventually takes over, almost in heroic mode, to a striking ending of the movement. Inattentive listeners often think at this point that the symphony has ended and break into spontaneous applause. But the darkest part of the symphony—it’s closing movement—is yet to come.

The intense, melancholic melodies of the final movement are possibly autobiographical, mirroring his personal battles with depression, self-doubt and questions of self-identity and sexuality.

Tchaikovsky’s “Pathétique” Symphony is a remarkable fusion of personal and societal reflection. It stands as a testament to the composer’s emotional struggles while also serving as a poignant musical embodiment of the tumultuous times in which it was created, making it a masterpiece that continues to move and resonate with audiences worldwide.

By Anjan Ray. This piece was originally published by the National Centre for the Performing Arts, Mumbai, in the December 2023 issue of ON Stage – their monthly arts magazine.