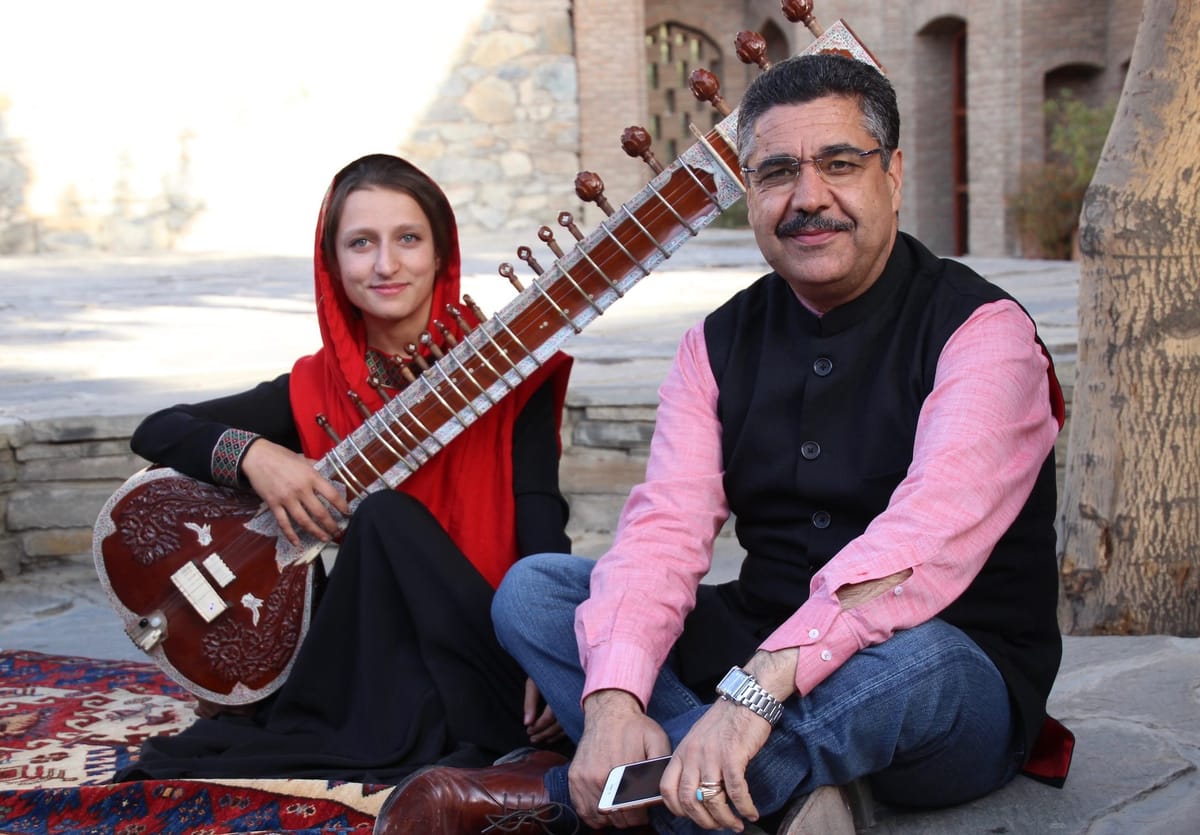

Dr Ahmad Naser Sarmast – Founder and Director, Afghanistan National Institute of Music

Nikhil Sardana: What are your earliest memories of being exposed to music?

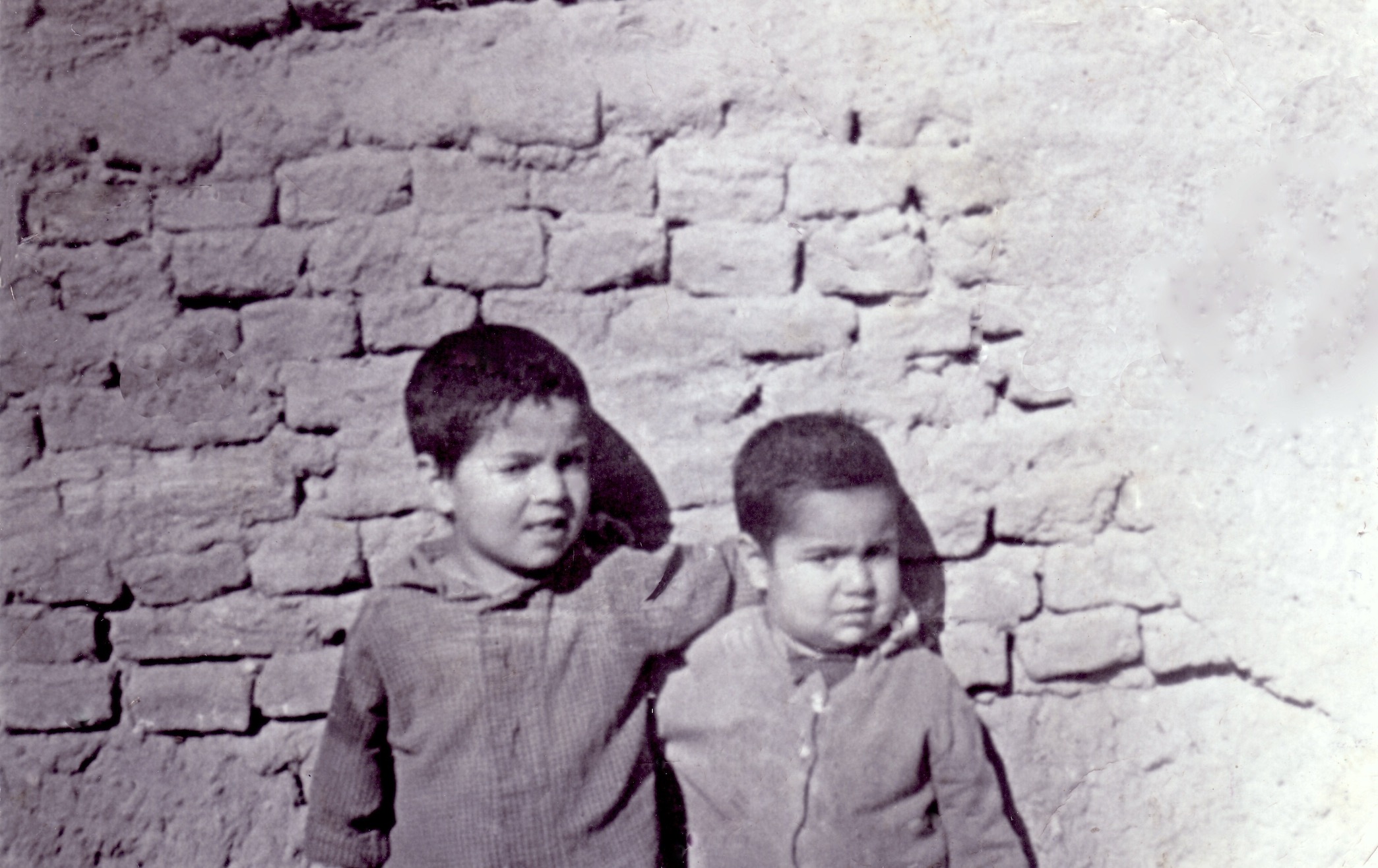

Dr Ahmad Naser Sarmast: I was born in the family of one of the most well-known conductor, songwriter and composer of Afghanistan – Ustad Salim Sarmast. Given the environment within our family, which was most of the time hosting Afghan musicians that worked with my father, I was always the first one to get to the guest room and listen to music.

I grew up in Kabul, Afghanistan at a time when this country was very sophisticated. My early memories with music are connected with the Independence celebrations back in the late 60s/early 70s. Over the course of a week, every evening had various organisations host Afghan musicians from all genres of music. What inspired me the most was this group of Afghan musicians called Four Brothers who were very much like The Beatles. Their fashion sense, instruments, style and performance was very similar to the infamous band. It was after watching this group perform live that I decided to enter the music world.

After completing my Grade 6, I enrolled myself in the Secondary Vocational School of Music in Kabul. I am the only person, amongst my two brothers and four sisters, to follow the profession of my father.

NS: Where did you go from here on? Tell us about your move to Australia. What was the experience like and how did you spend your time there?

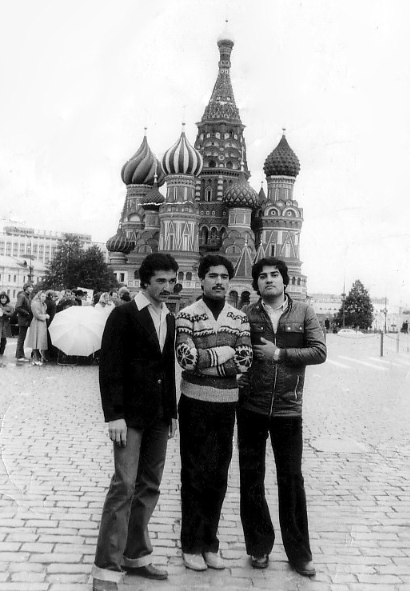

AS: Before going to Australia, I studied in the Soviet Union for 10 years. I got my Bachelor’s and Master’s degree from the Moscow Conservatory.

While I was finishing my Master’s degree and was full of energy, commitment and enthusiasm to go back to Afghanistan to implement the skills and knowledge I had received, that is when the political situation changed. It was 1992 when the Islamists came into power and their first steps were towards banning music and widespread discrimination against musicians. This took place right after the collapse of the regime of Mohammad Najibullah, the last secular president of Afghanistan.

Moscow was not a signatory of the International Immigration Convention. This left me with two options – either I return to Afghanistan and face the consequences or apply for a refugee status in other countries. I was very fortunate to receive this status in Australia.

Life there was not easy in the beginning as I did not speak a word of English. My priority was to learn the language and then utilise my skills and knowledge within the field of music. After several attempts of slowly finding my way, I sent my credentials for recognition. Unfortunately, that was the time when the Cold War got over and numerous regulations against the Soviet Union worked against me. My Master’s degree in Australia was assessed as a Bachelor’s degree and my Bachelor’s degree as a Secondary College Certificate. In order to stay within the field of music I had to go back either to school or pick up a low skilled job in Australia.

I learnt English and went back to school to pursue a Master’s degree and then my PhD in Australia to become the first Afghan with a PhD in music.

NS: How did you come about establishing the Afghanistan National Institute of Music? Tell us about your encounter with this gentleman from the World Bank at New Delhi airport. How did you come about acquiring the funds from the World Bank to support your cause?

AS: I returned to Afghanistan in 2006, right after the collapse of the Taliban, to witness the impact of years of draconian policies that worked against musicians and resulted in their migration to other countries. I wanted to work towards ensuring the musical rights of the Afghan people, assist with discovering their musical identity and strive towards rebuilding the Afghan musical tradition.

My report from this visit, Music in Afghanistan Today, was published widely on the internet and in a number of international music journals. Several recommendations were made with a focus towards assisting this nation to find its musical place within the world map of music.

I visited Afghanistan again in late 2006 and in 2007 to continue my research and submitted a proposal to the Ministry of Education for the establishment of a school with a music education program for the disadvantaged and marginalised class of Afghan children – girls, orphans and street kids.

My proposal was accepted and I was invited back in 2008. The international donor community at the time was not supporting arts education and culture. My struggle was to convince and educate them about the importance of music towards establishing a civil society and supporting the recovery of a traumatised nation like Afghanistan. I left for Italy the same year to present my project at one of the largest international gatherings of music educators. On my return I was waiting for my connecting flight from New Delhi airport when I started to chat with the person sitting next to me. On being asked why I was headed to Afghanistan, I shared my dream to transform the lives of Afghan children and society through music education.

I practically made a non-formal presentation to this gentleman. And by the end he asked why I wasn’t submitting a proposal to “us”. On questioning who “us” were, he said World Bank Afghanistan. I arrived in Kabul on a Tuesday. By Thursday lunchtime I received a phone call from the Minister of Education who said that the people I met at New Delhi airport were in his office and just agreed to give me $2,000,000 for my project.

NS: What was your reaction when you got this call?

AS: I wasn’t expecting this at all! My dream project receiving this grant was a big surprise for me.

Two million dollars for the World Bank is practically nothing to give to a music education program which is very expensive. At the same time, as my communication began with them, I made sure they understood the concept and outcome of this project. Their initial funding was used towards basic infrastructure and the purchase of musical instruments. Ever since 2008, the Afghanistan National Institute of Music which is part of the Ministry of Education now, has been on the payroll of the World Bank.

NS: Tell us more about the Afghanistan National Institute of Music. How many students are currently enrolled in your programs? What are the various music initiatives offered and how successful are your orchestral projects?

AS: The Afghanistan National Institute of Music was officially inaugurated on 20th June 2010. Our program also involves general education for the Afghan children. The music course is made up of two elements – traditional and Western classical music.

We have 250 students at the institute and one-third of the student body are girls. In 2010 we began with one girl but given the commitment of this school towards gender equality and its vision towards the improvement of social, political and cultural status of women in Afghanistan, we make our best efforts to ensure that more than 50% of new entries every year are female students. Thanks to this vision and commitment, we now have around 80 female students in the school. We also have a full orchestra, Zohra, consisting of 40 wonderful young girls that perform together with Afghan and Western instruments.

Our youth orchestra which is the only orchestra in Afghanistan and the largest ensemble of our school has performed at Carnegie Hall, The Kennedy Centre, Royal Opera House Muscat, and various performance venues across Afghanistan.

NS: What sort of challenges have you faced while running this institute in Kabul?

AS: We have many challenges here. We are living and working in a country which is emerging from war. We are working in an environment which is surrounded by people that are very hostile to music. The same people who banned music and deprived the people of Afghanistan of their musical identity and the very basic human right to express themselves through music. Bureaucracy and corruption are other significant challenges.

The biggest challenge is security. We did not have this problem at the very beginning. A day after the inauguration, I did receive a warning from the other side about them being upset with this establishment. However, I did not believe that the insurgency would be attacking cultural and educational initiatives until the year 2014 when a concert by our students at the French Institute of Afghanistan was attached and I was badly injured with hearing loss on both sides. Till date I have to undergo further procedures for recovery. Most of my time now is spent dealing with the forces of the country and beefing up the security around the school and putting all the measures that are necessary to protect our 250 children and faculty.

NS: Facing such resistance, why do you continue with your work? Why do you think music is important in Afghanistan today? Why is it important to save your cultural heritage?

AS: We are not facing resistance from the majority of the people of Afghanistan. We have a very rich musical history. Music was always a vibrant part of Afghan society and lives. We had a wonderful musical identity and today when I’m working here with my team, we have the support of the majority of the people of Afghanistan.

There are people who are very hostile towards music. But everything is worth it. Someone has to do their job and stand against these dark forces. Someone should make sure that the people of Afghanistan are not losing hope. The people should be able to express themselves freely and fairly towards music and its education. Someone has to fight for the happiness of our citizens and children.

Music education develops so many wonderful skills. It teaches our students to be patient and respect each other’s differences. It teaches them to live in peace and harmony in the same way they communicate and support each other. I am doing this not to be a hero. I only wish to make my small contribution to a brighter future for our people. I strongly believe that without investing in arts and culture, it is impossible to bring stability to this nation. Music can play a significant role in the reunification of Afghanistan.