Different strokes

ON Stage brings you excerpts from the NCPA Quarterly Journal, an unsurpassed literary archive that ran from 1972 to 1988 and featured authoritative and wide-ranging articles. The concluding part of a feature by musician and ethnomusicologist Ashok D. Ranade on categories of music talks about what demarcates popular music from art music and the two from other categories.

Popular music is one feature of a subculture known as popular culture. It is, therefore, helpful to define popular culture and prepare the conceptual background for a discussion of this musical category. ‘Popular culture is a surficial manifestation of cultural forces operating in a society partially responsive to aesthetic motives. The partial aesthetic responses are chiefly results of three factors: impact of the mass media, repercussions of the changes in patronage, and intermittent as well as interrupted functioning of commercial and religious pressures.’

One more factor needs to be noted before the characteristics of popular music are discussed. It must be remembered that ‘popular’ is not an aesthetic concept. Along with some other terms such as ‘amateur’, ‘professional’ and ‘modern’, the term ‘popular’ has socio-economic, cultural and chronological aspects.

Popular music: Breaking it down

As a consequence, to discuss popular music is to bring in extra musical values and criteria. Considering the fact that a large segment of the total musical reality of any modern society is represented by popular music, it deserves special attention.

– Universality: Universality has two aspects—chronological and territorial. Popular music is universal for all practical purposes.

It would be incorrect to assume that it is a special creation of the 20th century. The intensive American study of the category and the phenomenal growth of the mass media—a prominent shaping influence in the category during the century—have resulted in a tendency to confine the emergence and operation of popular music to present times. However, this is not strictly valid.

The primary cause for the genesis of the category is the simultaneous existence and independent operations of various subcultures in a society. It is obvious that a homogeneous society is purely a theoretical concept. All societies have subcultures operating at various levels and at varying intensities. In other words, social homogeneity and the equality of subcultures are ideals or possibilities only in a Ramrajya. In reality, all the subcultures in a society do not take to art music but are more attracted towards folk and popular musical expressions. To conclude, society is characterised by inevitable socio-cultural distinctions leading to musical differentials. The situation in turn causes a circulation of musical forces, in the process creating the ever-changing category of popular music.

– Popular music is subject both to ‘middle-class’ influences and to the effects of urbanisation. The fact of being a multi-layered society and the processes of urbanisation are causally related. If ‘industrialisation’ is not interpreted too technically, it implies recourse to new modes of production and the employment of new means for the purpose. The migration from rural areas to cities for earning one’s livelihood and the emergence of a new technology recur so frequently that they can be described as regular historical features of all growing cultures.

– Various factors contribute to a situation where more and more people enjoy leisure hours. They tend to be engaged in hobbies and seem keen to spend time on personality development or enrichment. As a consequence, various disciplines like arts, crafts, etc., are often pursued with motives that are semi-aesthetic and semi-commercial. Popular music is one of the products of such a situation. Entertainment, education, the desire for commercial gain and other diverse drives are simultaneously operative in popular art.

– The mass media have a special role to play in relation to popular music and deeply influence its conception, propagation and reception.

– It has often been suggested that when popular music finds roots in any culture, there is a perceptible rise in population. Large-scale redistribution of population on account of migrations is also detected. It has already been pointed out that the lack of homogeneity in a society is a precondition for the emergence of popular music. Population growth becomes a significant factor because a smaller population is likely to be more homogeneous than a sizeable populace. The latter tends to inevitable stratification, which in turn gives rise to popular music.

– Various socio-economic and cultural developments contribute to a change in the patronage offered to artists, craftsmen and cultural communicators in general. For example, the source of patronage passes from princes, zamindars and religious sects, etc., to music conferences and music clubs or circles, broadcasting and television stations, gramophone companies, etc. This is a qualitative shift. There is a noticeable difference in the discerning powers of the audiences created by the new patrons. One of the consequences is that performers feel a need to find the lowest common denominator in music receptivity. On a majority of occasions, this is the reference point around which popular expression tends to range.

– The change in patronage affects popular music almost immediately (which is not the case in folk and art music). The responses of audiences to producers and propagators of popular music allow for a very short time lag. In other words, popular music is a category that perhaps exhibits the greatest synchronisation between supply and demand.

– This remarkable near-correspondence of stimulus and response is because popular music is a product of the entertainment industry. Supply and demand, production costs, distribution and sale, market survey and research, etc., build up an entire mechanism related to production rather than creation. In popular musical operations, art and aesthetics are, if needed, nonchalantly relegated to the background. That is why popular music can hardly be understood if its business compulsions are not taken into account.

– In a manner of speaking, the most important motivation for popular music is the satisfaction of the more obvious musical needs of the masses. Art music tries to manipulate the time dimension and thereby win ascendancy over it, and folk music goes around it. Popular music, on the other hand, deliberately attempts to keep pace with the times. Import, expression, titles, blurbs and write-ups on disc/cassette recordings, therefore, attain their final shape only after the ruling fashion of the day has been ascertained. This is the reason why popular music may be described as ‘journalistic’ treatment of musical material.

– Popular music is functional in the sense that it is tied up with a specific mode or fashion which society prefers at a point in time. Fashions have a task to perform: the creation of easily manipulated devices of image-building or image-reinforcement. By their very nature, fashions have to change frequently. To create popular music is to create musical fashions.

– It may appear that popular music is more likely to be musically inferior because a majority of its shaping forces are non-musical. However, this is not so. A heartening feature is that popular music demonstrates a spiral rise in quality. Examination of the musical material reveals that it gives credence to the concept of progress in music. On account of its alertness and proneness to changes, it proceeds from music of lesser quality to one of better quality. Popular music which appears later in time may be superior because itsassimilative genius ensures more of acceptable musicality after a reasonable lapse of time.

Art music: What it stands for

(i) The most significant feature of art (or classical) music is the aesthetic intention of the performers. Here performers are set apart from musicians in the other categories because of their basic ‘art’ intent. The product, however, does not necessarily enjoy aesthetic validity because of the motivation. What is certain is that one cannot overlook the qualitative difference between the respective motivations of a primitive, folk, popular and art musician. In the field of primitive music, the performer is engaged in playing a role; the folk musician entertains or participates in a collective duty-filled task; the performer in popular music caters to a mass need; and the art musician seeks to establish himself as an artiste according to his own understanding of aesthetic norms or criteria. These may or may not be explicitly verbalised but their existence is beyond doubt.

– Art music is distinguished by the simultaneous operation of two traditions: scholastic and performing. Of necessity, the former relies on writing and the written text. More importantly, it follows the procedures inherent in every form of codification. Rules, methods and techniques pertaining to music are systematised in accordance with established practices. It is obvious that the scholastic tradition depends on the existing performing tradition for its raw material, but inevitably, the former lags behind the latter. This is because scholastic traditions are equipped to take cognisance only of those items that have consolidated or crystallised in the life pattern of a society. A helpful conceptual parallel for the phenomenon exists in the mutual relationship between grammar and literature in any linguistic tradition.

– Art music necessarily concentrates on select performing aspects such as vocalisation, instrumentation, movement or abhinaya. In other words, it displays less of a package character in comparison with musics that belong to other categories. Art music channelises or deliberately isolates modes of expression and cultivates them intensively in order to achieve greater and perceivable effects. This is why art music performances can be easily described as concerts of vocal or instrumental music.

– It is art music which offers scope for ‘solo’ performances. In no other musical category are the roles of the main and the accompanying performers so clearly defined and differently developed. To isolate the solo element and allow it to shape the entire performance requires a highly differentiated sensibility. To this end, art music formulates aims, methods and techniques specifically leading to the emergence of family traditions, schools, etc., with their own marked personalities.

– In art music, one is confronted with a whole array of musical forms, chiefly based on patterning the general musical elements in specific structures of notes, rhythms, tempi, etc. On the other hand, non-art musical categories abound in forms which owe their existence to non-musical factors such as events in human life cycles, seasonal changes and associated rites and rituals. Forms in art music also evince the existence of a hierarchy based on the degree of technical In other words, certain forms are regarded as more prestigious because of the demands they make on the skill of the performers. On examination, highly musicological criteria are found to have been employed to erect the hierarchy.

– Art music features a highly structured teaching-learning process. As a consequence, gharanas come into existence, gurus enjoy an exclusive following, reputations as effective teachers are built up, disciples are initiated with due ceremony and musical pedigrees are traced and treated with respect as well as pride. Methodical curricula come into existence even if they are not necessarily written down; material complementary to teaching-learning, such as anthologies of compositions, notations, codifications are prepared, preserved and often guarded with utmost secrecy.

– Audiences of art music are a class apart on account of their non-participatory contribution. Compared to other musical categories, art music depends for its efficacy on the presence of more organised audiences who are expected to have developed a taste, preparing them to receive the sophisticated impact of art music. Perhaps no other musical category finds it so essential to educate its audiences. Further, the audience is also expected to contribute to the making of a performance by expressing appreciation or disapproval in accordance with established norms forming part of a total cultural pattern. Acquisition of a taste for art music or its appreciation includes learned behaviour, and it is symptomatic that attempts at conducting appreciation courses in this category are well received.

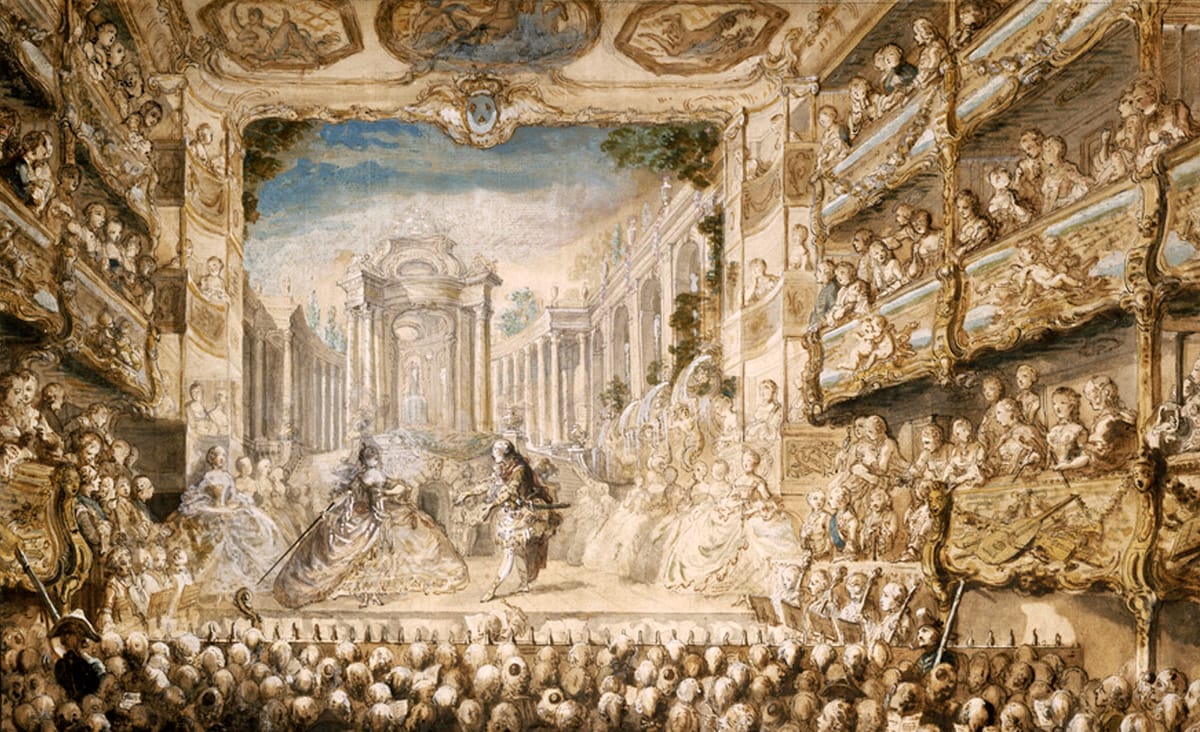

– Art music is also characterised by its all-round efforts to combine with other forms to create composite art and art forms. The process appears a little paradoxical in view of the purposeful delinking with other arts in the first place. However, the paradox disappears once the differing motivation is appreciated. The delinking of art music from other manifestations initially takes place so as to enable it to demarcate its area of operation and effectively develop its own special identity. On the other hand, the later efforts to effect a reunion with dance, drama, painting, etc., are designed to enrich the total aesthetic experience. The emergence of ballet, opera, ragamala paintings can be traced to this enrichment motive.

– At every level, art music employs abstraction. For example, it diminishes the scope afforded to language and literary manifestations, reduces the importance of topical and functional relationships with rituals and routine life patterns. As a cumulative effect of these measures, it creates its own universe of reference and tries to adhere to a contextual framework of musical elements alone. Therefore, the non-representational, patently arabesque quality of art music is often commented upon, and the qualitative similarity of art music to the world of mathematics is repeatedly averred. Abstraction necessarily means a total dependence on musical parameters for perception of music, and this explains the comparatively confined appeal of art music as music.

This article was originally published from the Archives section by the National Centre for the Performing Arts, Mumbai, in the September 2021 issue of ON Stage – their monthly arts magazine.