Diary of a Visionary

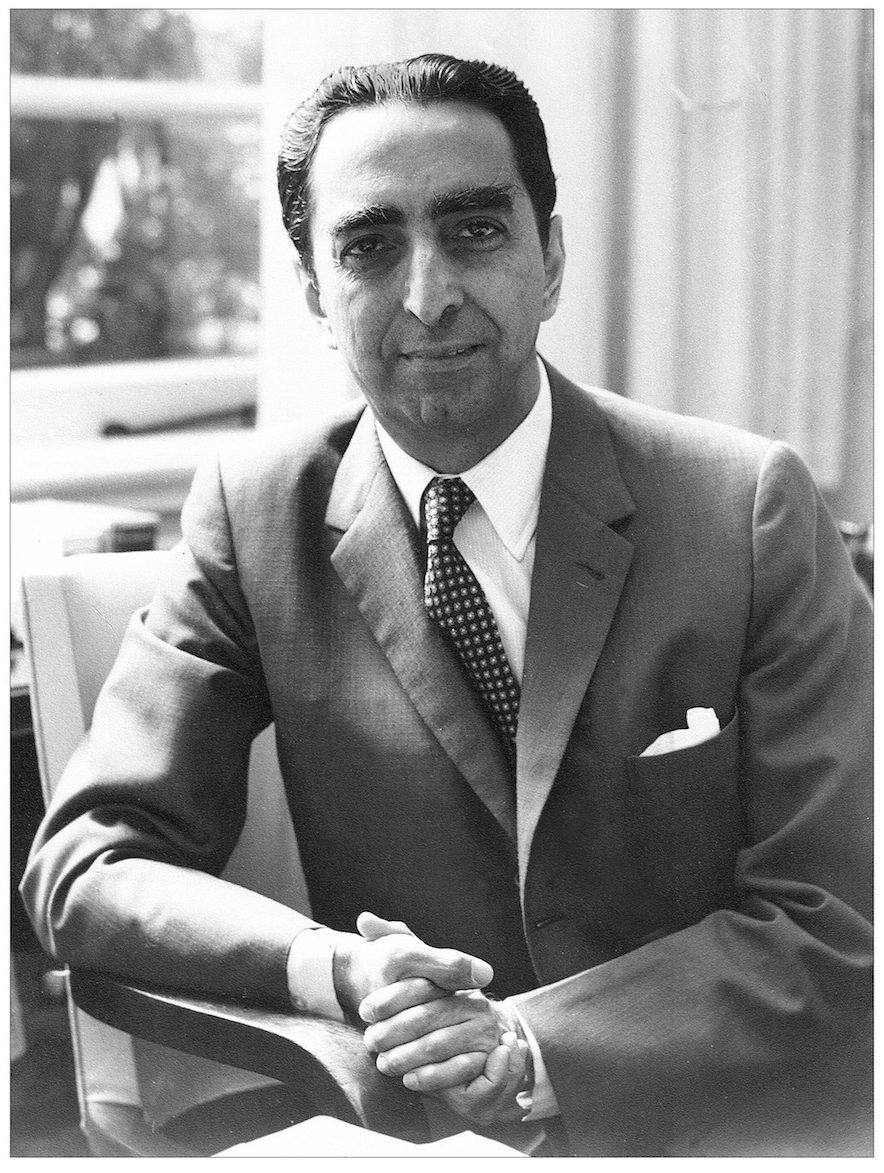

From reclaiming new land to finding the right acoustics, Dr. Jamshed Bhabha had to undergo every struggle imaginable to launch the NCPA. By Anil Dharker

“We will build the NCPA on this part of the Arabian Sea.” These could well have been the words of Dr. Jamshed Bhabha as he stood on the edge of Marine Drive at what was then Bombay’s new business district – Nariman Point. The origins of India’s national cultural centre (for that is what the National Centre for Performing Arts undoubtedly is) are fascinating. It began with a note Dr. Bhabha presented to the trustees of the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust. The trust had already set up the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore, the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, the Tata Memorial Centre for Cancer and the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research. Why not, Bhabha’s note said, a pioneering institution in arts and humanities? The concept note for the NCPA (then called the National Institute for Performing Arts) was based on the fact that Indian classical music, classical dance, folk music and dance were all dependent on oral traditions sustained by the guru-shishya parampara, the master-pupil link.

These flourished under the patronage of India’s princely rulers over the centuries, but now that privy purses were abolished, and princely states were gone, who would support them? Would they, then, suffer the tragic fate of Ancient Greece? The architecture, sculpture, drama and philosophy of Classical Greece had survived because they were preserved in a tangible form. Greek music, which one can assume was as developed as the other art forms, had, however, disappeared because it relied on oral traditions. Bhabha’s proposal went against the conventional wisdom of the time. We were then in a phase of nation-building. Science, technology and industry were considered its foundations, and something that favoured music and dance seemed almost frivolous. Convincing the trustees was not easy.

The brotherhood

Why did Bhabha think differently? Those who knew the brothers, Homi and Jamshed, and the milieu they were brought up in, find this unsurprising. Mr. Khushroo N. Suntook, Bhabha’s close collaborator in his later years and who succeeded him as the NCPA’s Chairman, knew the brothers from the time he was a schoolboy. He remembers cultural trips to Europe – to the great art centres of Florence and Vienna; of meeting the famous critic Bernard Berenson in his Florentine villa; of being taken by the curator on a tour of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence and looking in wonder at its collection of Raphaels and Botticellis; of being shown the subtleties of da Vinci’s left-handed strokes. This informal tour lasted five months and the brothers were an intrinsic part of it. Suntook also remembers evenings spent in the Bhabha home. “My job as a schoolboy was to turn the records on the gramophone to play the other side.” The music, even then, was all Beethoven, largely his quartets.

With a background like that, it is hardly surprising that Dr. Homi Bhabha, the great nuclear scientist, was still a lover of the arts – music and painting particularly (he was an accomplished painter himself). And it is hardly surprising that even when his younger brother held important positions in the Tata group like Vice Chairman of Indian Hotels (the Taj Mahal hotel group), Managing Agent of TISCO, Chairman of Tata McGraw Hill and others, he still held culture and the arts closest to his heart.

The promised land

So in 1965, when he got the mandate he wanted from the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust to start the NCPA, he was not unduly deterred by its central condition – he had to get land from the government to set it up. The NCPA needed five acres. Bombay, the government said, did not have five acres to spare. However, he could have an even greater piece of land if the NCPA could be located elsewhere. Where was elsewhere? Near the Ajanta caves.

This is when Bhabha came up with the out-of-the-box idea of asking for a piece of the Arabian Sea. It says something about his persuasive powers that the government actually agreed to this outlandish idea. The bit of sea initially allotted was in the middle of Marine Drive, opposite the Taraporewala Aquarium. For various technical reasons, this was unfeasible, which is how the present location was chosen. The ‘plot of land’ was the sea reclaimed at a cost of Rs 50 lakhs, not a small sum in those days. Forty lakhs came from the trust and the balance from other sponsors.

But while all this was going on, the NCPA had already taken off. In 1969, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi inaugurated a small centre at 89, Bhulabhai Desai Road, consisting of small dance and music practice rooms, reading and listening libraries and a 100-seater auditorium. This earlier avatar of today’s Little Theatre was, believe it or not, the cultural hub of the city. I remember it well from the ’70s when I came to Bombay – there were weekly dance, music, poetry performances and, if I remember correctly, New Wave cinema screenings. The auditorium on the first floor was always packed, and we in the audience felt privileged. The NCPA had taken wing.

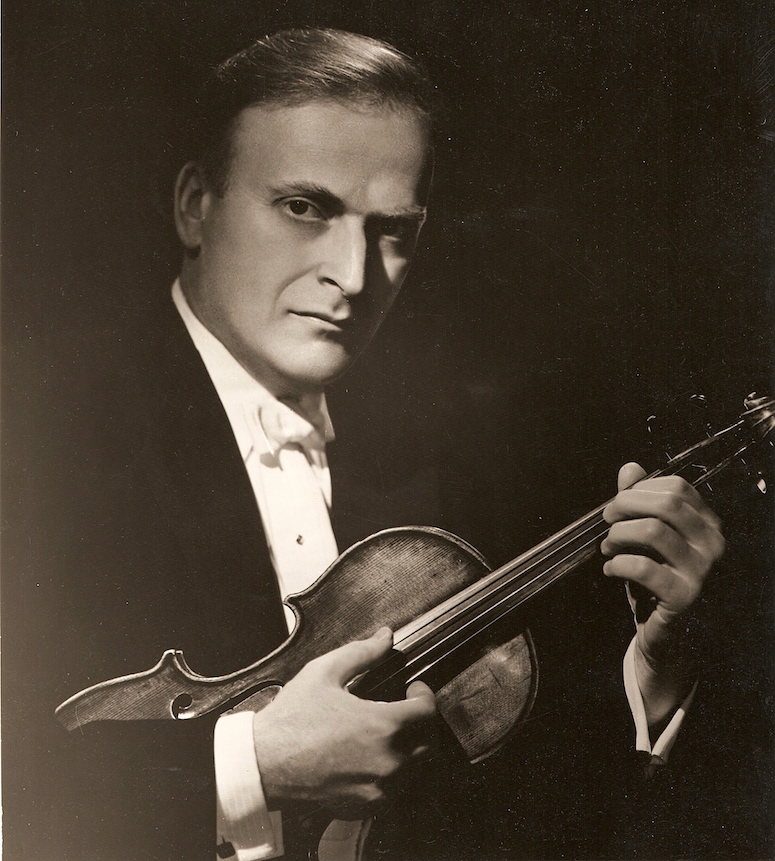

“There is absolutely no doubt that without Dr. Jamshed J. Bhabha’s selfless dedication, the NCPA would not be what it is today. I had the pleasure of knowing him since my earliest visits to India from 1967 onward and rejoiced with my Mumbai friends when the magnificent hall had its opening. The Bhabha family has been close to mine ever since my father’s initial friendship with the illustrious Dr. Homi Bhabha, who would have been immensely proud of his brother and, had he survived, to enjoy the beautiful music that Jamshed brought to our city. I congratulate Khushroo Suntook and all his co-workers on this most auspicious anniversary and I regret not being present at the celebrations.”

Zubin Mehta on Dr. Bhabha

A leaf from every corner

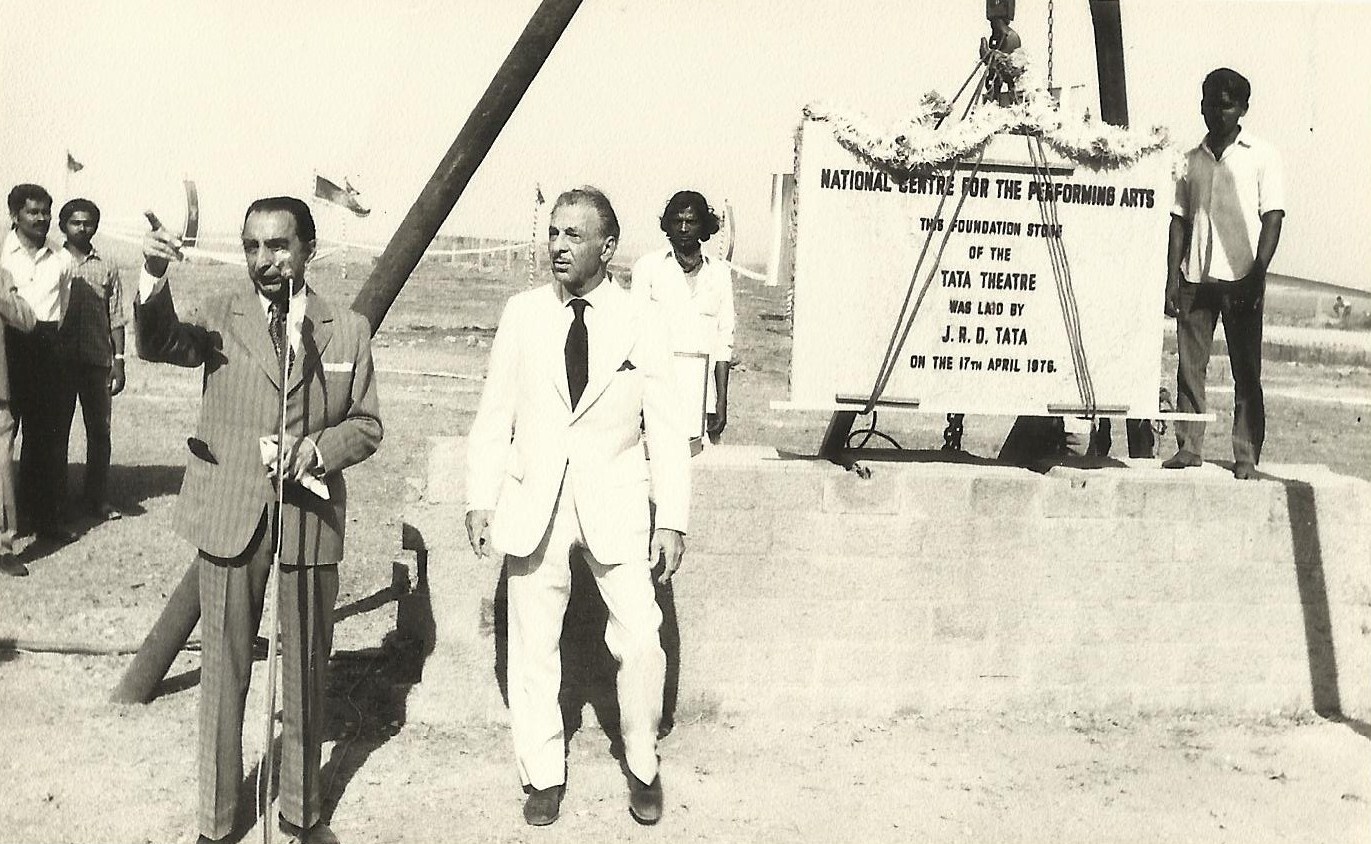

The building of the Tata Theatre took Bhabha all over the world. “While I was in Paris in 1966 for a UNESCO meeting, I attended a reception given by the United States Ambassador to France,” Bhabha wrote in an article. “While I was admiring the model of the interior of the Opera House of the proposed John F. Kennedy Centre for the Performing Arts in Washington, I became conscious of someone standing near me.” This turned out to be Edward Durrell Stone, the architect of the centre and the US Embassy in Delhi.

Later, visiting Stone’s office in New York, Bhabha wistfully remarked about how he would like something similar for his NCPA in Bombay. “But we have a foreign exchange shortage, so that’s out of the question.” Stone’s reaction was incredible: Bombay’s National Centre could have Washington’s Kennedy Center designs and all the drawings free of charge. Bhabha was later able to squeeze out a similar offer when he went to Los Angeles. This came from Welton David Becket, architect of the Los Angeles Music Center, and a friend of Zubin Mehta, who was then music director of the Los Angeles Symphony Orchestra.

However, the idea of transposing a design from abroad lock, stock and barrel into India was wisely dropped, and Philip Johnson, one of the world’s great architects, was commissioned to design the Tata Theatre. Johnson made several trips to Bombay and attended musical recitals and dance programmes. He noted our tradition of the audience sitting around the artistes and our vocal expressions of appreciation. He decided, therefore, that the theatre he would design would not be of the normal shoebox rectangular design, but a fan-shaped one, a bit like a Greco-Roman amphitheatre.

Bhabha then went to a number of places in America in search of the perfect acoustics. When he found what he liked, he met the man responsible, Professor Cyril Harris of Columbia University. As it happened, Harris and Johnson had vowed never to work with each other because of a previous unpleasant experience, but it says something about Bhabha that they not only agreed to collaborate on the Tata Theatre but worked on several US projects together after that.

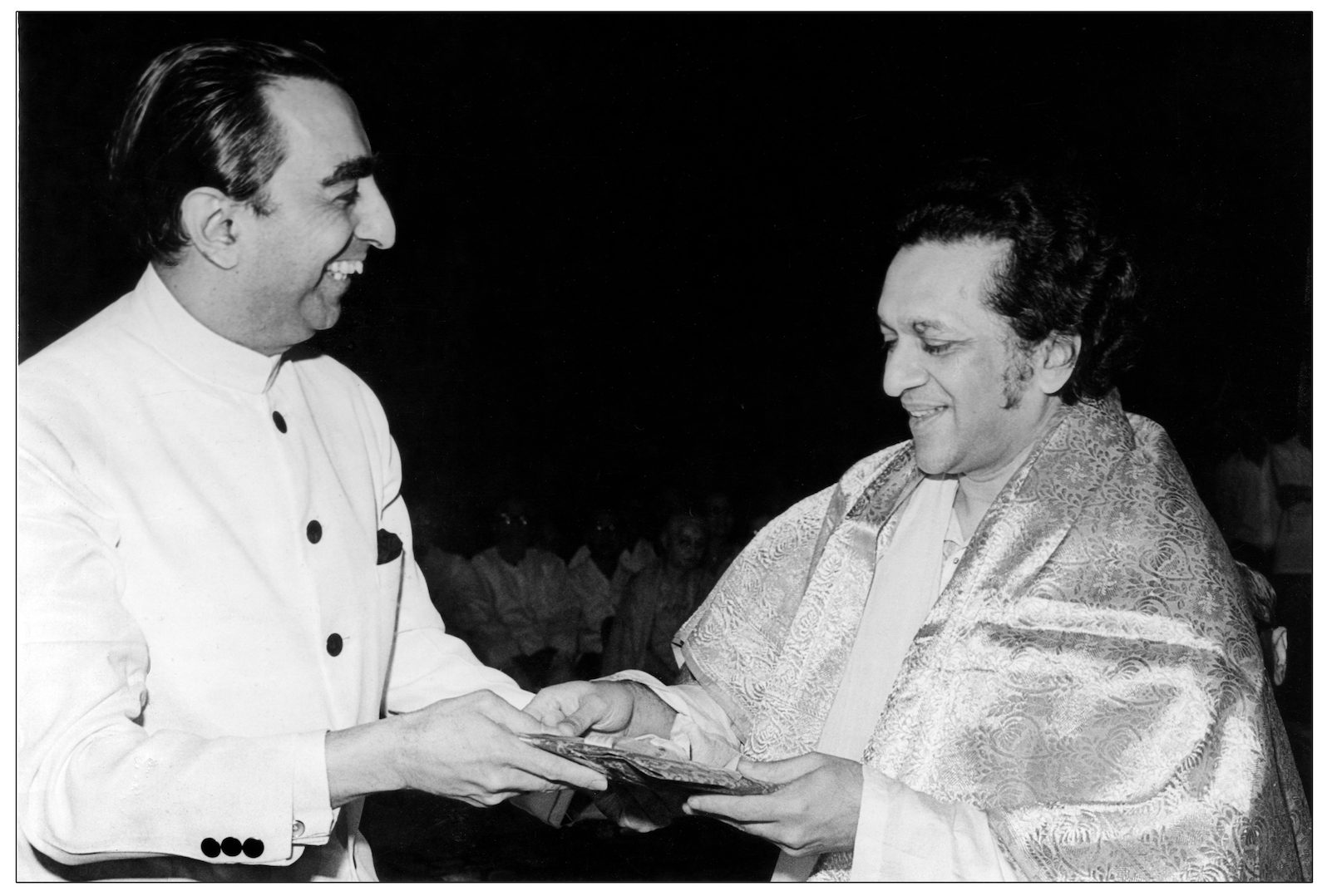

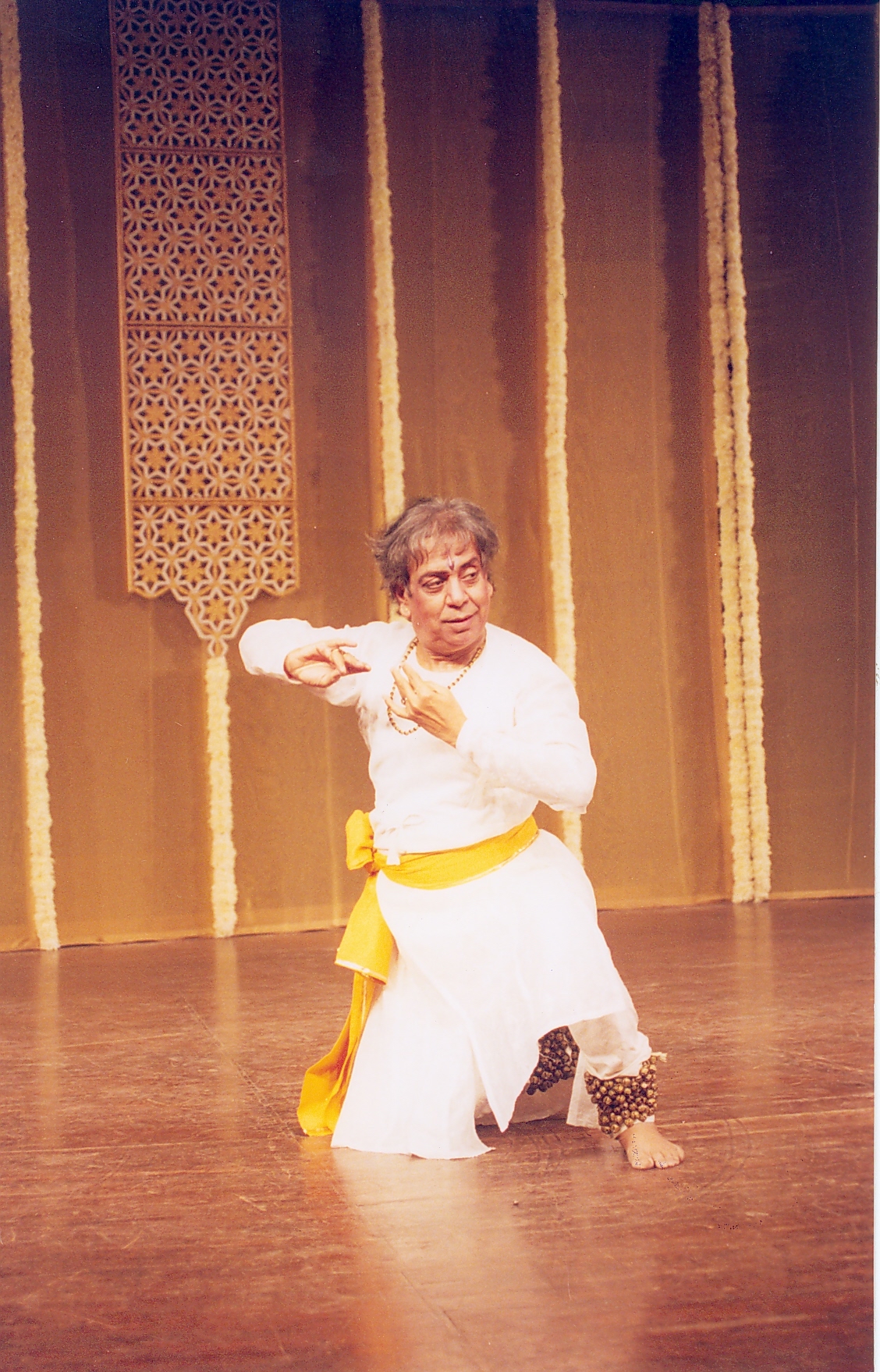

The Tata Theatre, though it seats over a thousand people, retains a sense of intimacy so essential to performances where a dancer’s abhinaya (expression) needs to be seen. Its acoustics, even today, are a marvel, and wherever you sit you can hear the smallest whisper from the stage without amplification. Bhabha was extremely proud of this. You may have heard the story of Ravi Shankar, but it is worth retelling. The sitar maestro wanted to perform at this spanking new theatre and expressed a desire to see the auditorium. Bhabha took him around. Shankar was overjoyed with what he saw. Except for one thing. “But there’s no amplification,” he said. “We don’t use mikes here,” Bhabha explained. “The acoustics are so good that we don’t need them.” “But I don’t perform without mikes,” Shankar said. “In that case, we will have to do without your performance,” Bhabha replied.

The perfect sound

Tata’s perfect acoustics are not achieved just by Cyril Harris’s meticulous design: the Philip Johnson building, unknown to all its users, is actually three buildings, each with its own separate pile foundation. This is to prevent any structure-bound sounds from entering the auditorium, which is an independent structure, as are the entrance lobby and staircase, and the portion abutting the back entrance. Bhabha would tell people proudly, “Even if a road drill was used, no sound or vibration will be transmitted to the auditorium.” By the way, even the terminal points of the water pipes on the toilets have rubber connections to exclude transmission of vibrations. Such perfection comes at a price, but the Bhabha magic persuaded both architect and acoustic consultant to waive their fees, and the Ford Foundation to give a large grant.

Some of the Tata’s earliest programmes were the path-breaking Indo-German collaborations, which Vijaya Mehta, the doyenne of Marathi stage, directed. “If Shakuntala, Hayavadana and Nagamandala happened, it was because of Jamshed. It was through his initiative too that Peter Brooke’s troupe came to Bombay and toured India. There were seminars, workshops – it was exhilarating,” says Mehta.

“Dr. Jamshed Bhabha had a vision for greatness. A vision for art to be showcased at one of the greatest centres of art in the world – the NCPA, his gift to many artistes and audiences alike. Including me. I too have been fortunate to have performed in the various theatres of the NCPA. I have also had the opportunity of sitting and listening to some great music with Dr. Bhabha at the NCPA, a number of times. His love for the arts and his passion to find a way to preserve and nurture it was always evident. The music fraternity owes him a big thank you.”

Zakir Hussain on Dr. Bhabha

An equal music

The mystery to me is how Bhabha, with his background and upbringing, which was so focussed on Western culture, became such a champion of India’s traditional art forms. “He knew by instinct what needed support,” says Mehta. “He didn’t have a particularly thought out or articulated theory on these things. He just knew what was right.” That must have dictated his choice of the first executive director of the NCPA, Dr. Narayana Menon, former director-general of All India Radio and a renowned musicologist. He was followed by P. L. Deshpande, popularly known as Pu La, the biggest name in Marathi literature. He was followed by Vijaya Mehta. All of them products of, and deeply steeped in, Indian culture.

What was Bhabha like to work with? According to Mehta and many others who worked with him, “He was childlike in many ways – almost a spoilt child. If he wanted something, he had to have it. If he didn’t get it, he threw a tantrum. If he liked an idea of yours, he became like a man possessed. You could then be sure he would turn the idea into a reality,” says poet and curator Arundhathi Subramaniam, of her time at the NCPA, when Chauraha, an interactive arts forum dreamed up by Vijaya Mehta, was spearheaded by Subramaniam for 15 years. “Chauraha was possible because Dr. Bhabha backed the idea that the creative process is as important as the end result. In all those years, there was absolutely no interference, and above all, no pressure on me at any point to feature only high-profile artistes, to glam up an event or to measure its success in economic terms. Venues like the Audio Visual room, the Little Theatre and the Sunken Garden were offered free of charge. Dr. Bhabha was paternalistic and autocratic, but he was, without doubt, a true patron of the arts,” says Subramaniam.

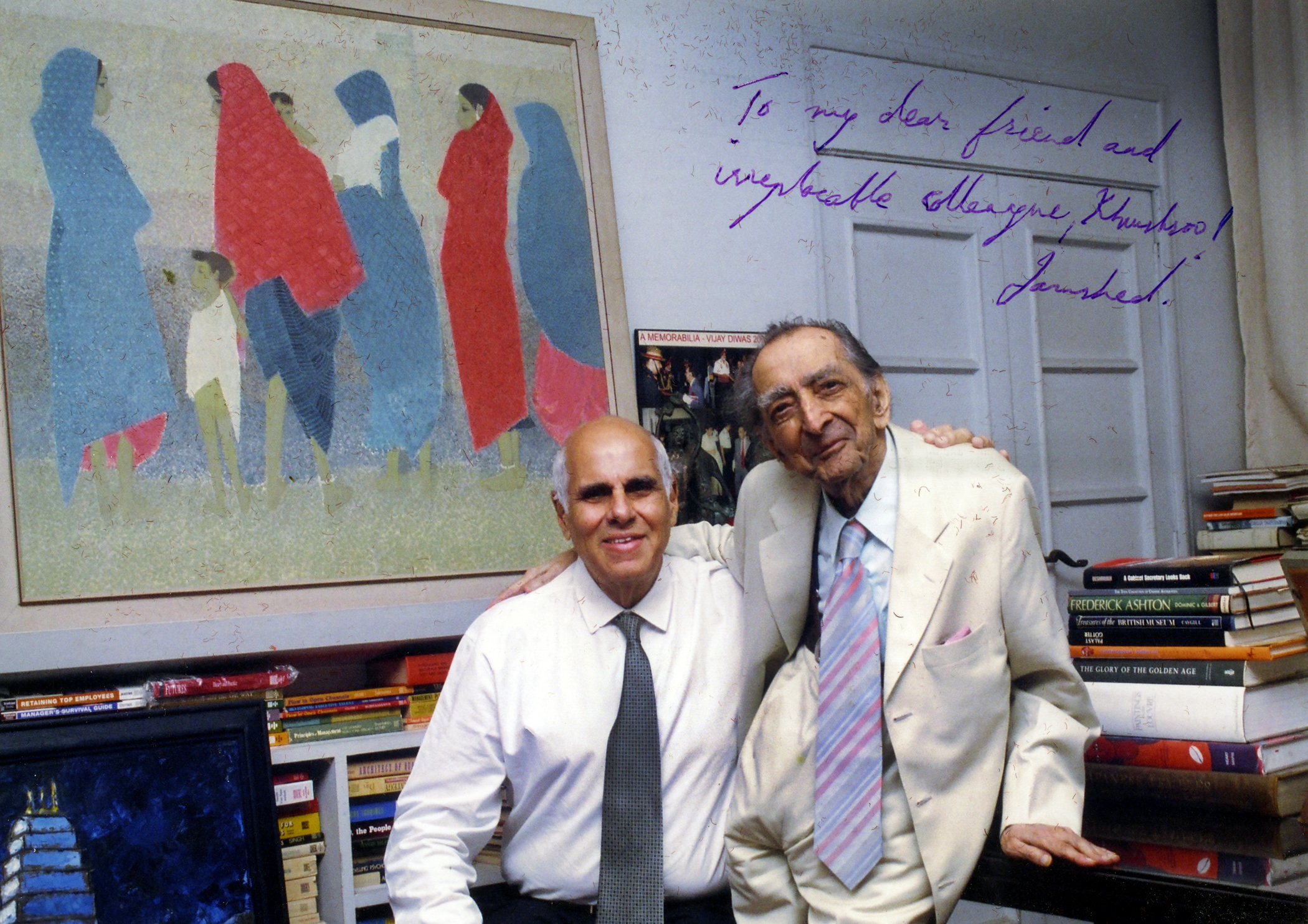

With so many diverse events taking place and so many of them being offered free of charge, how did the NCPA make ends meet? “We didn’t,” says Suntook with a laugh. “However, you must remember that when it came to raising money, Jamshed was a charmer.” He remembers Bhabha’s legendary teas for people he liked or was wooing for raising money. “Coffee or tea? Darjeeling or Assam? With milk or without? Hot milk or cold? Sugar or sweetener?” However, if he did not like someone, he would say, “Bearer, chai aur biscuit lao.” No elaborate tea ceremony then, no special cake or savouries. Another time, meeting a lady of considerable means, who was identified as a possible donor, Bhabha called her home for lunch, told her delightful stories about his visits abroad and about wining and dining with royalty. He then sent her home with an extravagant present. A few days later, he rang Suntook. “Dikra” he said, “That was a complete waste of time. She is giving us nothing.” It was one of his rare failures.

One-man army

But if everything failed, Bhabha had Bhabha himself. Suntook remembers a major – and vital – fund-raising drive, which though successful, did not raise enough. “We have come up short,” Suntook said despondently to Bhabha. “How short?” “Well, a crore.” Next thing he knew, Bhabha had sent someone to fetch his cheque book. Out came his pen, and out came a cheque of one crore. Another time when the NCPA was struggling to pay salaries and sundry bills, Bhabha wrote out a cheque for Rs 27 lakhs with the words, “When I am gone, your worries will be over. You will have a couple of hundred crore to keep the NCPA going.” He was referring to his will by which he had bequeathed his Malabar Hill bungalow and its contents to the NCPA.

“His dedication to the NCPA and to the cause of culture was complete,” says Suntook. “His motto was: when the cause is good, the money will follow.” A splendid example of this came up when Suntook took the idea of setting up the Symphony Orchestra of India. “I went to him with great trepidation,” he says. “When he heard me, his first reaction was, ‘You must be mad.’ His second reaction was, ‘How much will it cost?’ At no time did he discourage me.” The SOI’s success is an achievement of staggering proportions, one often overlooked in counting how many Indian heads feature in the orchestra. The heads will follow – what has been set are standards that compare favourably with international benchmarks.

Bhabha’s crowning glory, among many crowning glories, is the Jamshed Bhabha Theatre. It is a state-of-the-art, all-purpose theatre that can be used for plays, opera, ballet and concerts. It even has an orchestral pit that can go up and down. But contrary to what some might think, it is not an act of self-aggrandisement. Bhabha had decided to call it the National Theatre, and it was only at Suntook’s insistence that it should be personalised, that the name was changed. But while that change came in time, another one did not. JBT was supposed to be inaugurated by the President of India. The President’s trip was cancelled at the last minute and the Governor of Maharashtra did the honours. The plaque at the entrance to this day, however, claims that JBT was inaugurated by the President.

The shoulders of a giant

That would not have displeased Bhabha. A famous story about him has him pick up his phone and tell his secretary, “Connect me to the Prime Minister.” “The PM is busy, Dr. Bhabha. Should I connect you to the Deputy Prime Minister?” asks the secretary. “How often have I told you,” Bhabha angrily remarks, “that I never speak to the number twos?” In his cabin, Suntook has a photograph of them together. “That’s the last picture of him.” Suntook says. In the photograph Suntook is seated while Bhabha stands affectionately near him. “He made me sit down. ‘You are too tall,’ he said. ‘I don’t like people to be taller than me.’” Obviously, Bhabha meant that literally. He must have known, as indeed he should have, that there would not be very many men around, however accomplished they were, who could, in any real sense, be really taller than him.

This article was originally published by the National Centre for the Performing Arts, Mumbai, in the August 2014 issue of ON Stage – their monthly arts magazine.