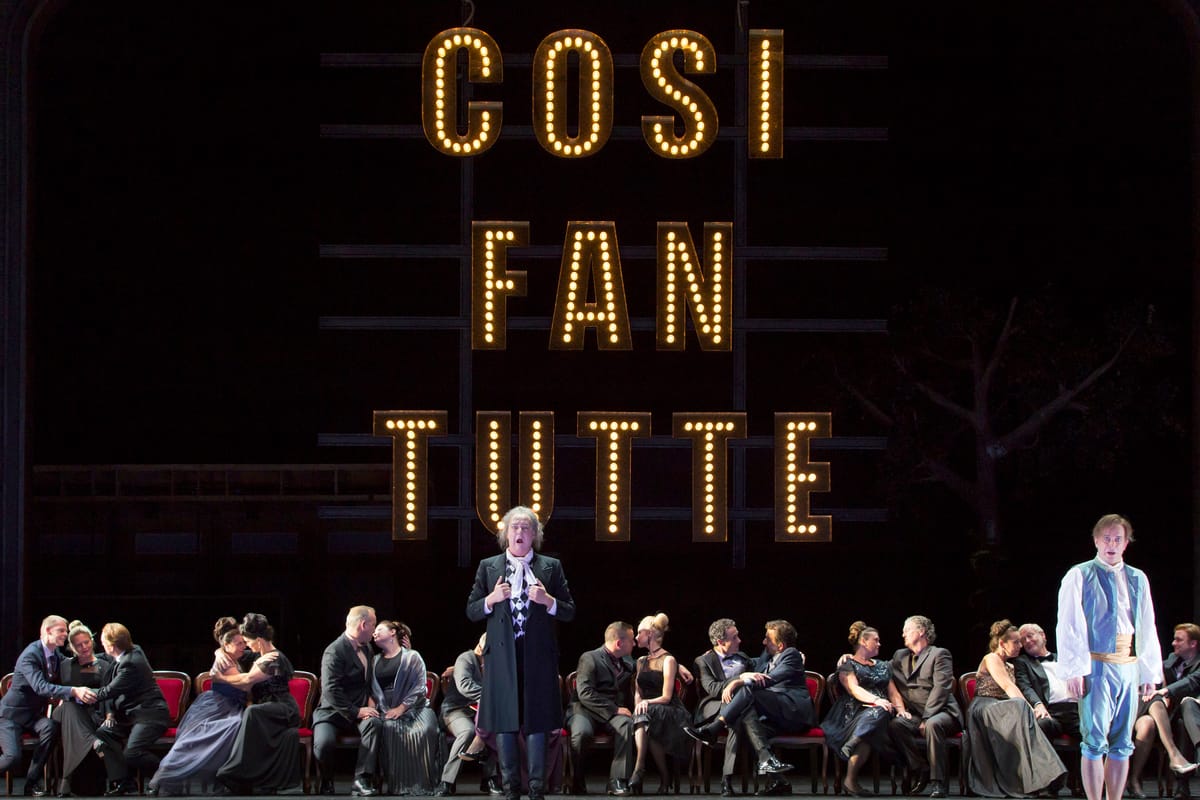

Of Doubts, Desires and Duties: Così fan tutte at Royal Opera House, London

In the introduction to the book, Opera Buffa in Mozart’s Vienna (1997), Mary Hunter and James Webster write that ‘Opera Buffa’ fell between art and entertainment. Cutting across contemporary topics and characters, it was open to a variety of aesthetic strands. It always had one foot in the contemporary whereabouts, and the other foot firmly rooted in old traditions. Opera Buffa gives to its audience a sort of ‘improvisational comedy’.

What becomes particularly interesting in the context of Così fan tutte is Mozart’s indication of the cultural and intellectual trends of that particular moment in time, which was a significant motif for most of his works.

Tia De Nora’s article in the book, ‘The Biology Lessons of Opera Buffa: Gender, Nature and Bourgeois Society on Mozart’s Buffa Stage’, is quite compelling while reading the performance at the Royal Opera House, conducted by Semyon Bychkov on the 17th of October 2016.

She links Così fan tutte to the Viennese enthusiasm for Botany and the eroticism undergirded in the formulation of plant life. In this context, she mentions the towering influence of Carolus Linneaus’ ‘Systema Naturae’ during the 1770’s. Nikolaus Jacquin known as the ‘Austrian Linnaeus’ and his son, Joseph Franz, who was known primarily for his tour of the European Botanical Centres, around the year 1788, together, influenced Vienna’s social and cultural scene to a large extent. The Jacquins also opened their home for a weekly discussion session for artists and scholars. Mozart, who became quite close to the younger son of Nikolaus Jacquin, Gottfried Jacquin, attended these sessions regularly, ever since their acquaintance in 1783.

During the 1780’s and 1790’s, notions of plant sexuality and plant nuptials or the ‘lawful marriage of plants’ became a topical concern in the project of Botany! It was further discovered that unlike the lawful marriage of the humans, only one order of plants, the one husband or the monoandria class – monoandrian – monogy – nias practiced monogamy. This apart, the plants reproduced in a variety of polygynous and polyandrous relations. Tia De Nora mentions few other scholars to support her argument. Wye Allanbrook typically talks about the ‘feminine inconstancy’ depicted in Mozart’s operas through pastoral tropes. Therefore, Opera Buffa was just another workspace vis-à-vis fiction and painting, where women’s character, in this case, fidelity was interrogated. Wheelock talked about the minor mode dedicated to Mozart’s female characters and the implicit idea of weakness.

Thus, it comes as no surprise that the weaknesses of the two sisters, Dorabella and Fiordiligi were exploited in the garden, often viewed as the nature’s laboratory. There were two gardens relevant to the seduction plot, the garden by the seashore and the pretty little garden. The garden is also where Ferrando and Guglielmo, disguised as foreigners, feign death due to rejection.

The librettist Da Ponte’s symbolism for the apparently restrained Fiordiligi, another name for the flower, Lily, brings forth the hues of innocence and infidelity during ‘Fra gli amplessi’. Somehow it comes across as more tormenting than ‘Il core vi dono’ where Dorabella succumbs to Guglielmo’s advances a little more joyfully. Tia De Nora posits her Biology lessons to flesh out the ‘classical episteme’ predominant in the 18th century obsession with classification and taxonomy emphasised by Michel Foucault.

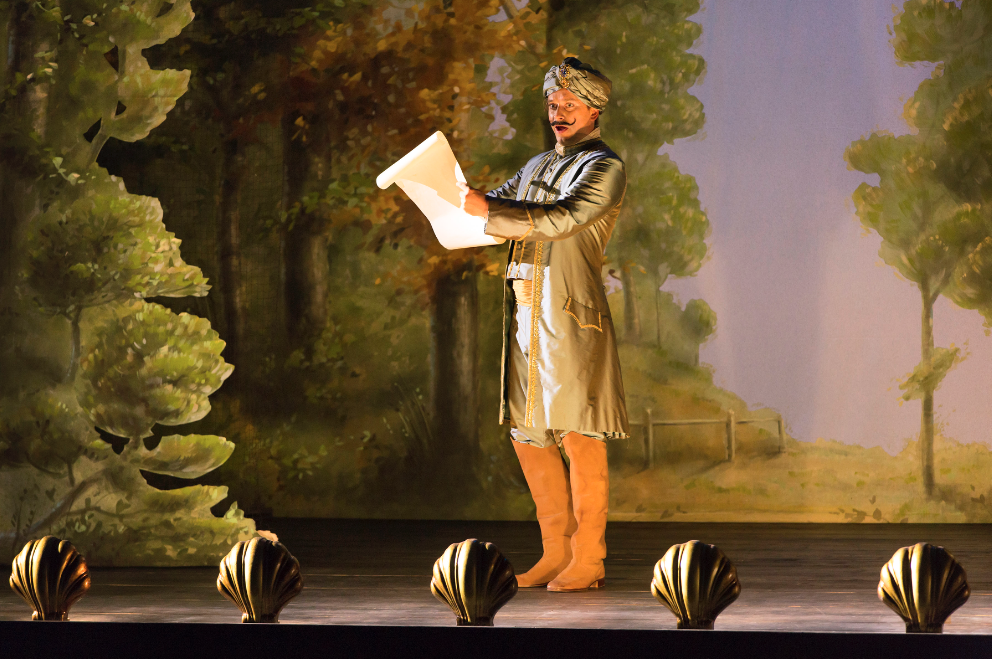

Women’s inconstancy being the obvious motif, I find that ‘Alla bella Despinetta’ brings out the complete oblivion expressed by Ferrando and Guglielmo in the wager game suggested by Don Alfonso. The original lovers pretend to go to war and come back disguised as Wallachians. But it depends on Despina, the maid, to make the sisters realize what the society thinks of women and eventually execute the frivolity, the society expects of them! Romance is categorized as futile and irrational, therefore, quite naturally driven by feminine desires. Men on the other hand, are shown to partake of its amusement and anguish in a much more passive way. If emotions have gone awry, the inconsistencies of women are to blame. Men afterall are more attuned to working out the scientificity. In this case, Don Alfonso’s tried and tested patterns of wooing women subscribes to the idea of rationality. In the end, nothing remains the same but it helps each one embrace forgiveness.

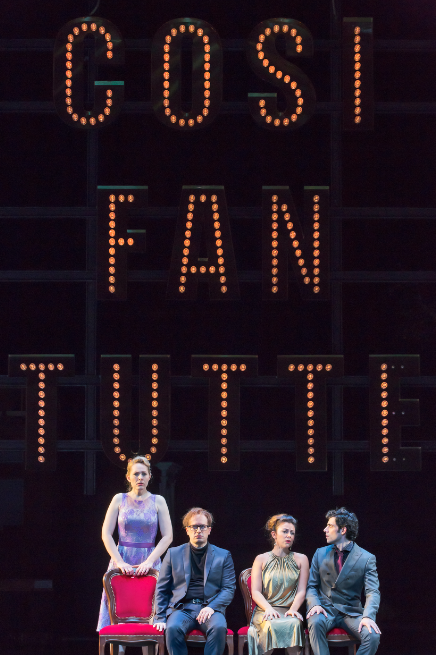

Mozart brings back ‘Opera Buffa’ with a new twist, much different from the reigning influence of Carlo Goldoni in Vienna of the early 1760’s. Here, it is a good idea to refer to Paulo Gallrati’s article from the same book on Mozart and 18th century Comedy. He does point us to the direction that Mozart’s Opera Buffa does not restrict itself to the comedy line of the Italian sensibility. It goes on to incorporate the European theatrical dynamics in its totality. Mozart is well known for the ‘fourth wall’ built into his works, and this particular production by the Royal Opera House, uses it well to bring out the nuances of the human frailties. Women are expected to portray chastity and symbols of undying love. Their lovers however, are at liberty to get carried away while putting them to test. This production, subtly brings forth the inconsistencies experienced by the male counterparts. The inhibitions and arrogance played out by Ferrando and Guglielmo questions the significance of the category of ‘amorousness’, rather than the agencies which define it. The contemporary references in the form of station, bar, etc. render the necessary timelessness to the theme. The space in front of the stage is used as the space for introspection, for the characters. Thus, the element of opera within an opera is explored. Dorabella’s aria, “Smanie implacable” for instance, helps one gauge the transition from histrionics to deeper, private emotions.

As the director Jan Philipp Gloger says to dramaturg Katharina John – “This work is terrifyingly honest and tells us that we human beings are at odds with ourselves and that also shows us that infidelity can sometimes be more serious in our imagination than it is in reality.” This current production of Così at the Royal Opera House is after twenty years! Alessio Arduini, Daniele Behle, Angela Brower, Johannes Martin Kränzle, Sabina Puértolas and Corinne Winters, who comprise the core cast, played their respective role with absolute finesse and coordination.

Così fan tutte

The Royal Opera

22 September—19 October 2016

Main Stage

Music: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Cast:

Corinne Winters

Angela Brower

Daniel Behle

Alessio Arduini

Johannes Martin Kränzle

Sabina Puértolas

Creative Team:

Libretto – Lorenzo da Ponte

Conductor – Semyon Bychkov

Director – Jan Philipp Gloger

Set Designer – Ben Baur

Costume Designer – Karin Jud

Lighting Designer – Bernd Purkrabek

Dramaturg – Katharina John