Clocks, Clouds and Textures

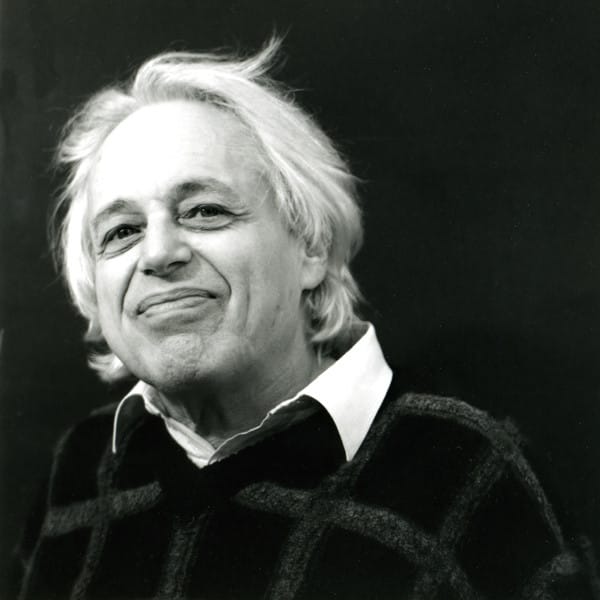

On December 10, 1956, in a remarkable struggle for survival and artistic freedom, György Ligeti (1923-2006), one of the most important composers of the twentieth century, boarded a train under the cover of night and escaped from the politically turmoiled Hungary. Hiding from the Soviet army, patrolling in the border, he endured a dangerous and difficult journey by freight trains and on foot and crossed illicitly into Austria. Eventually, with the help of Karlheinz Stockhausen and Herbert Eimert, he secured a place at the Studio for Electronic Music in Cologne, and thus a new era in his life began.

Ligeti was born on May 28, 1923 in a Jewish Hungarian family in a small Transylvanian town. Though he received his first Piano lesson at the age of fourteen, he soon showed serious talent in composition and at the age of sixteen wrote his first Symphony. After the end of the Second World War, he enrolled at the Budapest Music Academy and studied counterpoint, fugue, instrumentation and free composition with Sandor Veress, Ferenc Farkas, Pál Kadosa and others. Following the footsteps of Bartók and Kódaly, Ligeti too collected hundreds of Transylvanian folk songs and adapted them to different instrumentations. However, soon after composing the Romanian Concerto in 1951, he realised that he must distance himself from the Bartokian tradition and find his own style.

Through the concept of masse sonore or sound mass, as opposed to melodic, harmonic or rhythmic motives pioneered by Varèse as early as the 1920s, Ligeti’s contribution was to achieve a coherence in the spatial context without doing away with the concept of voice-leading.

During 1950-1956, he taught harmony and counterpoint at the Budapest Music Academy, wrote two textbooks on classical theory of harmony and composed for various ensembles. However, due to the aesthetic impositions of the socialist doctrine, his progressive compositions, considered too dissonant, could not receive any public performance and ended up in the drawers. The New Music of the West was forbidden in Hungary in the 1950s. Ligeti became acquainted with certain works of Messiaen through the night programs of the German Radio stations. In 1956, he first acquired some scores of the works of Schoenberg, Webern and Berg and established contact with Stockhausen and Eimert. Later he recalled in an interview: “It was a great shock for me – perhaps the most beautiful of my life … it was like a liberation”. When the Soviet troops invaded Budapest in the November of 1956, he decided to risk everything and leave his homeland to escape the dictatorship and to be able to compose without stylistic restrictions.

At the studio of West German Radio in Cologne, he began working with composers like Stockhausen and Koenig and became acquainted with the intricacies of musical avant-gardism. His output from this period: Glissandi (1957), Artikulation (1958) and Pièce Electronique No.3 (1958), fabricated with pure electronic sounds, differed completely from his earlier neoclassical thematic compositions in the Bartókian tradition, like Musica Ricercata (1951-1953), the First String Quartet (1953-1954) and other works. In the studio of Cologne, Ligeti assimilated almost simultaneously, the technique of serialism and that of electronic music. The former permitted him to control the sounds with extreme precision of notation while the latter allowed him to seek the continuity of the phénomène sonore through the electronic medium. It is his experience in the electronic studio that engendered the orchestral compositions of pure sounds: Apparitions (1958-1959) and Atmosphere (1961); where he created very complex and densely knitted texture and abandoned thematic materials altogether. He amalgamated and assimilated the technique of serialism and electronic music into his own musical language to fuse massive harmonic structures with extremely precise contrapuntal writing which was unprecedented and radically different from the music of textures of his contemporaries like Penderecki and Xenakis.

His idea of form was mostly influenced by Webern, Debussy, Varèse and Messiaen. Several types of formal procedures can be identified in his compositions: the static form – as found in Atmosphere, the dynamic and fragmented form, like that of Aventure, the ‘kaleidoscopic’ form, made of separated and contrasting musical material, as in Dix pièces pour quintette à vent and so on.

Through the concept of masse sonore or sound mass, as opposed to melodic, harmonic or rhythmic motives pioneered by Varèse as early as the 1920s, Ligeti’s contribution was to achieve a coherence in the spatial context without doing away with the concept of voice-leading. One of the most important techniques that Ligeti devised during this period is called micro-polyphony: a canonic texture where several lines, separated narrowly in time and moving at different speeds, creates a dense harmonic field so that the individual lines become impossible to follow. Due to the highly dense nature of the canons, the polyphonic material cannot be heard. One can only hear a vertical homogeneity that changes continuously. The most famous example of this technique is the fifty six voice canon that Ligeti used in Atmosphere. He used this technique subsequently in his other compositions during the 1960s like the Requiem (1963-1965), Lux Aeterna (1966), Lontano (1967) and so on. In Ligeti’s own words, in Lontano,

“Polyphony is written but harmony is heard”.

Ligeti experimented with two extreme temporal approaches in his compositions: the system of ‘clouds’, where textural and timbral transformations are carried out in such a way so as to make the beat imperceptible for the listener and the system of ‘clocks’ or marked time, where the artificial division of time into equal units is used to imitate mechanical devices. At times, he used bars only as a mean of orientation and organisation – to facilitate the physical execution of his works for ensembles and intentionally avoided any sense of pulsation or meter to create a sense of timelessness. This process is observed in compositions like Atmosphere, Lux Aeterna, Lontano and others. He was also fascinated with the repetitive sounds of machineries, like the ticking of mechanical clocks and was particularly interested in the sounds of malfunctioned mechanical devices. This preoccupation with repetitive rhythmic patterns was musically manifested in Poème Symphonique (1962) for 100 metronomes, an experimental composition where all the metronomes are set to tick mechanically at different speeds, for different durations of time and their interactions produce a highly complicated rhythmic pattern, whose complexity decreases as the metronomes stop one by one. Later, he used this process in other instrumental pieces and himself named it as Pattern-meccanico compositions, where several overlaid linear strands created from small group of pitches are repeated rapidly in a mechanical way and the pitch content of the strands changes gradually. The first published piece to incorporate the Patter-meccanico technique was Continuum (1968) for Harpsichord.

Ligeti considered the form as a process of temporal transformation and avoided consciously the developmental and hierarchical formal models. To him, all moments in a musical composition were of equal importance. His idea of form was mostly influenced by Webern, Debussy, Varèse and Messiaen. Several types of formal procedures can be identified in his compositions: the static form – as found in Atmosphere, the dynamic and fragmented form, like that of Aventure, the ‘kaleidoscopic’ form, made of separated and contrasting musical material, as in Dix pièces pour quintette à vent and so on.

The summary of all these compositional techniques can be found in the Second String Quartet (1968) and in a composition for 12 part women chorus and Orchestra titled Clocks and Clouds (1973), shortly after which his compositional aesthetics changed into a new direction.