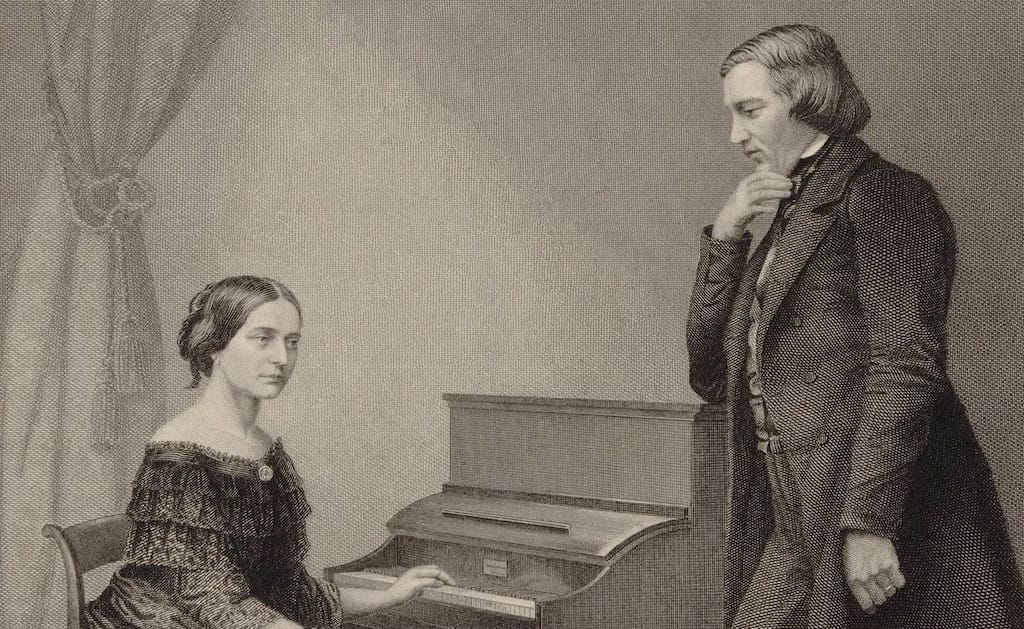

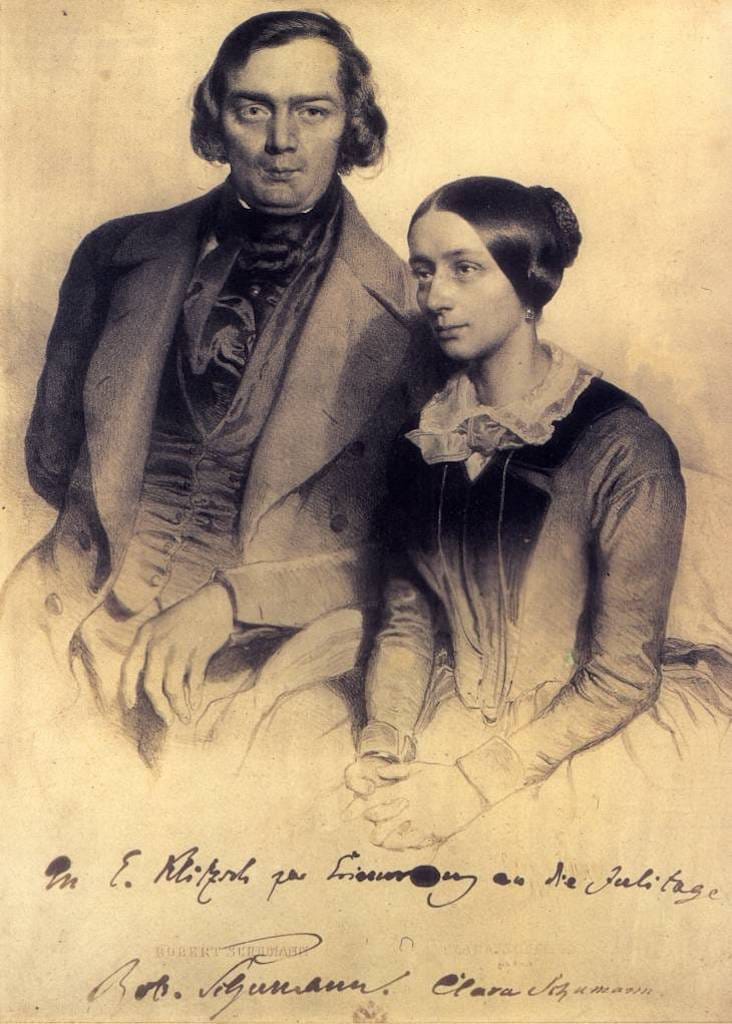

Clara and Robert Schumann: A Musical Partnership

Clara and Robert Schumann’s union transcended romance to become a rare, creative partnership. As composer, pianist and critic, Robert found in Clara not just his muse but an equal whose artistry and intellect shaped Romantic music forever.

In the realm of nineteenth-century music, few partnerships resonate with as much depth and passion as that of Clara and Robert Schumann. Their union was not merely romantic; it was a profound artistic collaboration, one that shaped the course of nineteenth-century music. Clara was not only Robert’s muse but also his equal in talent and intellect—a formidable pianist, composer and educator who forged a path for women in music at a time when such a role was rare. Together, their intertwined lives speak of creativity, struggle, inspiration and enduring legacy.

Early Lives and Musical Training

Clara Wieck was born in 1819 in Leipzig, the daughter of Friedrich Wieck, a strict and ambitious piano teacher who recognised her prodigious talent early on. Under his rigorous tutelage, Clara developed into one of the most celebrated pianists of her time. She made her formal debut at the age of nine and by her teenage years had already performed in major European cities, earning accolades from composers such as Chopin and Liszt.

Robert Schumann, born in 1810, was also drawn to music from a young age. Initially intent on becoming a pianist, he studied with Friedrich Wieck—thus beginning his acquaintance with the young Clara. However, a hand injury forced Robert to abandon his ambitions as a performer and instead devote himself to composition and music criticism. In 1834, he founded the influential Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, through which he championed the music of then-little-known composers such as Chopin and Brahms.

A Love Tested by Convention

Robert and Clara fell in love during her adolescence, but their relationship was fraught with obstacles. Clara’s father vehemently opposed the match, fearing that Robert—who had neither financial security nor social status—was unworthy of his daughter. What ensued was a bitter legal battle, culminating in the court granting them permission to marry in 1840, just a day before Clara's 21st birthday.

Their union marked the beginning of one of the most artistically fruitful partnerships in classical music. The year of their marriage, 1840, is often referred to as Robert's Liederjahr or 'Year of Song', during which he composed more than 130 art songs. Many of these, including the revered Dichterliebe and Frauenliebe und -leben, were inspired by his love for Clara and often based on texts that resonated with their shared emotional world.

Mutual Inspiration and Shared Ideals

Clara was far more than just Robert’s muse; she was his confidante, critic, and champion. Despite the demands of motherhood—she would bear eight children—Clara continued to perform, compose, and manage the household, often under considerable duress. Her concert career was essential to the family’s finances, especially during Robert’s frequent bouts of ill health.

Robert, for his part, held Clara’s musicianship in the highest regard. He encouraged her to compose, and many of their musical ideas flowed back and forth between them. Clara premiered many of Robert’s works and frequently offered detailed feedback on his compositions. Her deep musical insights are well documented in their voluminous correspondence, which provides a rare glimpse into their collaborative process.

Perhaps the most touching evidence of their partnership lies in the joint composition of their Lieder and the presence of musical motifs that reference each other. Clara’s Piano Trio in G minor, Op. 17, written in 1846, stands alongside Robert’s own piano trios as a work of exceptional emotional depth and technical command. Her music is imbued with lyrical beauty and structural clarity, qualities that aligned with the aesthetic ideals they both cherished.

Trials and Separation

The latter part of their life together was marked by tragedy. Robert’s mental health began to deteriorate in the 1850s, leading to increasing episodes of depression, hallucinations, and eventually, a suicide attempt in 1854. After voluntarily admitting himself to a sanatorium in Endenich, Robert would remain there until his death in 1856, having seen Clara only briefly during that time.

During these harrowing years, Clara turned increasingly to performance and to the care of her children. Despite her own suffering, she remained steadfast in preserving Robert’s legacy. She gave numerous concerts featuring his works, edited his collected editions, and corresponded with friends and admirers to ensure his contributions were remembered.

A poignant chapter of this period was Clara’s deepening friendship with Johannes Brahms, who had entered their lives in 1853 as a young, unknown composer. The bond between Clara and Brahms was intense, intellectual, and, some speculate, romantic, although there is no conclusive evidence of a physical relationship. What is certain is that Brahms adored Clara and remained devoted to her for the rest of his life, often referring to her as the greatest woman he had ever known.

Clara's Later Years

After Robert's death, Clara never remarried. She channelled her energies into a remarkable career that spanned decades. She continued to perform across Europe, gaining international recognition as one of the great interpreters of her husband’s music as well as that of Beethoven and Brahms. Clara was instrumental in shaping the Romantic piano repertoire and performance practice, championing works that would later become central to the canon.

Her influence extended to teaching as well. As a professor at Dr. Hoch's Conservatory in Frankfurt, she became one of the first women to hold such a post, mentoring a new generation of pianists. Her pedagogical writings and method books contributed significantly to the evolution of piano technique and interpretation.

Yet for much of the 20th century, Clara’s achievements as a composer were overshadowed by her fame as a pianist and as Robert’s widow. Only in recent decades has her compositional output—rich in innovation, emotional candour, and formal sophistication—received the critical attention it deserves. Works like her Three Romances, Op. 11, and Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 7, are now regularly performed and studied, reclaiming her rightful place in music history.