‘Cancel’ Beethoven?

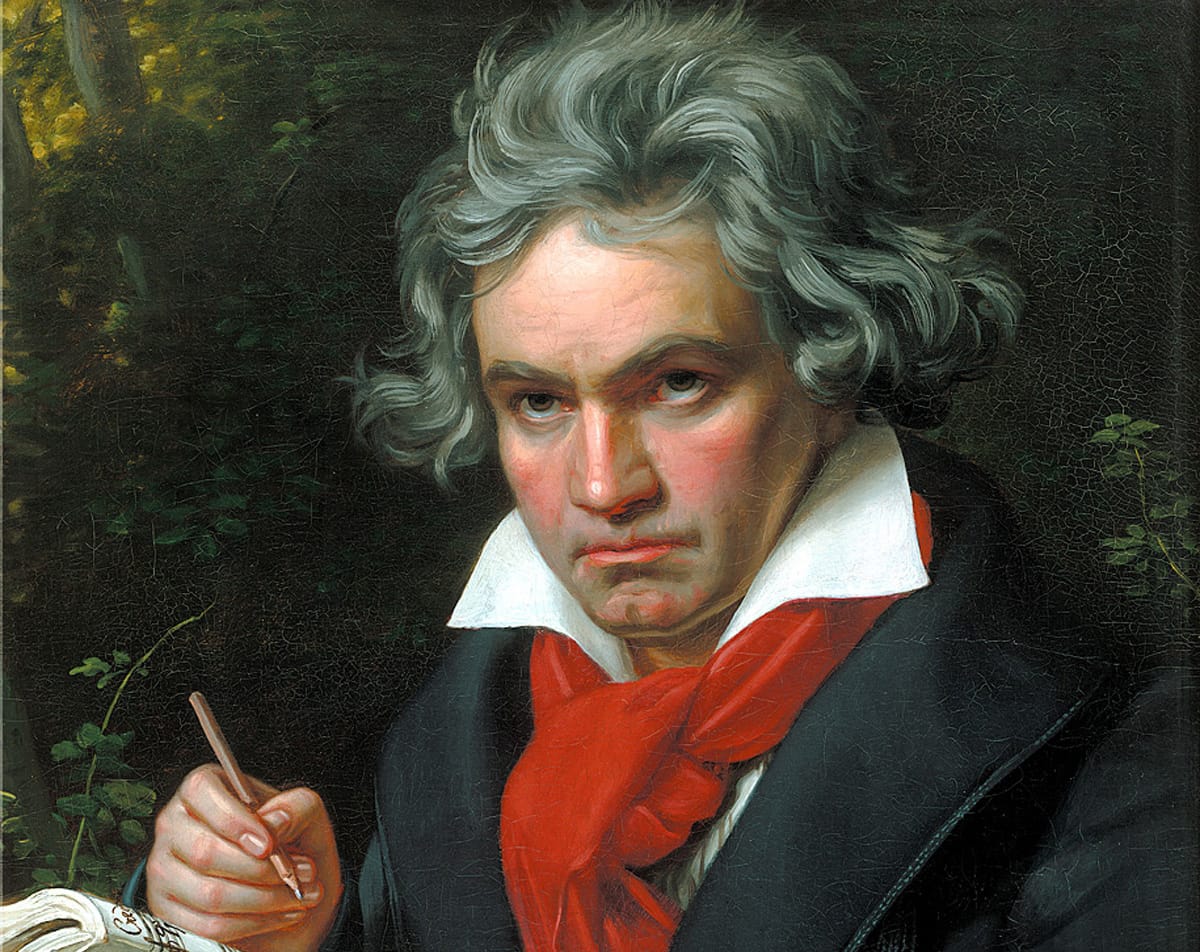

Until the Coronavirus got its vicious spikes all over it, 2020 was meant to be Beethoven’s year. He was born on 17th December 1770 in Bonn. (In Vienna, where he spent most of his adult life and died in 1827, they regard 16th December as his birthday). In either case, this is the 250th anniversary of his birth and both cities had planned year-long events, Germany as many as 300 with a budget of $30 million (over Rs 220 crore). But all is not lost for Beethoven lovers: festivities will now start in December and go on for 250 days, so ending in September 2021.

Nor is all lost for those who will use Beethoven for their 15 minutes of fame. Vox, an American news and views website, has a ‘Switched on Pop’ podcast whose stars are musicologist Nate Sloan and songwriter Charlie Harding. In a recent piece titled ‘How Beethoven’s 5th Symphony put the classism in classical music’ they say, ‘Wealthy white men embraced Beethoven and turned his symphonies into a symbol of their superiority and importance. For others – women, LGBTQ+, people of colour – Beethoven’s symphony (the Fifth) is predominantly a reminder of classical music’s history of exclusion and elitism… Maybe it’s time we break up with Beethoven once and for all.’

Cancel Beethoven? One could dismiss this as the latest stunt of publicity-seeking posturers, except for several reasons: They are both professionals in their field; they are both white males; their views were broadcast on an influential platform which is associated with the New York Philharmonic; and most important of all, this is not an isolated case, but just another example of the woke madness that has infiltrated the world of history and culture through the strident, joyless ideologues of the Left who are toppling statues and ‘cancelling’ even Shakespeare and Aristotle.

Fanatics on the Left and the Right have one thing in common: they are so convinced of the righteousness (or lefteousness) of their cause that they take leave of their common sense. So it’s pointless telling them that if privileged white males made the rules for culture, it is because the whole of Western society was like that, and PWMs made the rules for everything. In Beethoven’s time, women were subjugated (as this column examined last month), people of colour were second-class citizens at best, and the concept of gender fluidity was largely unknown. What did Beethoven have to do with all this? Or, particularly, his Fifth Symphony?

One suspects that this particular work was chosen because of its universal popularity: its opening notes, Da-Da-Da-Dumm, have been recognisable everywhere through all these years; in fact, their rhythmic pattern is duplicated in the Morse Code notation for the letter V, and was used by the BBC in its broadcast to Occupied Europe during World War II to signify V for Victory. The apt word for the Fifth is that it is ingrained in today’s culture. In fact, as Maddy Roberts of Classic FM says,

“The tense struggle of the opening, the endless switching between minor and major, and the final moment of triumph is relatable to today’s brave new world.”

To make Beethoven a symbol of privilege and exclusion is particularly idiotic because ‘Ode to Joy’, the Friedrich von Schiller poem the composer used in the final movement of his Ninth symphony, and its melody, have become symbols of freedom against tyranny. Even non-German speakers recognise its line ‘Alle Menschen werden Brüder’ (All mankind will become brothers). Demonstrators in Chile sang the piece against Pinochet’s dictatorship; Chinese students broadcast it at Tiananmen Square; Leonard Bernstein performed it at the fall of the Berlin Wall, and it was played in Japan to denote hope after the 2011 tsunami.

Woke critics also say that the formal etiquette of Western classical music concerts was imposed to show superiority and exclusion. As it happens, this is of more recent origin – it was only in the late 19th century that Mahler as conductor (and to some extent, Schumann) brought in today’s convention of listening in silence, with applause only at the end of a piece. During Beethoven’s time, cheering and clapping during a performance was common: in fact, at the premiere of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony, there was so much applause at the end of the second movement that the orchestra immediately played it again.

A report of the premiere of the Ninth is touching and happy at the same time. Beethoven, completely deaf by then, insisted on conducting the orchestra, but his earlier rehearsal had been disastrous, so Louis Duport stood at the conductor’s podium while Beethoven stood in front of him. According to a member of the orchestra, Beethoven “threw himself back and forth like a madman, stretching, crouching, flailing his hands and feet as if he wanted to play all the instruments and sing all the chorus parts.” When the symphony ended, Beethoven was several beats off and was still conducting. Caroline Unger, the contralto, gently took Beethoven’s arm and turned him around to face the audience. The packed hall went wild with applause, raising their hands, throwing their hats and handkerchiefs in the air so that the composer could see what he could not hear.

By Anil Dharker. This piece was originally published by the National Centre for the Performing Arts, Mumbai, in the October 2020 issue of ON Stage – their monthly arts magazine.