Building a Noteworthy Life

Eighteen years ago, when I married Luis on New Year’s Day, I could not possibly have predicted how dramatically our lives would change in just four years’ time.

When we got married, Luis was a doctor in the NHS (National Health Service) in the UK. He had just made the shift from Gynaecology to General Practice, in the pursuit of a more structured day, which would allow him to do the things he really loved—visit museums, travel, and play violin in one of London’s most celebrated amateur orchestras. I joined him soon after our wedding, quitting my desk job at a PSU in Mumbai, and leaving behind everything and everyone I had ever known.

I’m not a musician, but I enjoy listening to all sorts of music. I married a man who had become a doctor because he “had the marks and didn’t know how to pursue music”. Yet music, specifically western classical music, is the foundation of everything he has done in his life.

In 2007, Luis made a stray comment (after seeing children selling trinkets at a traffic light in Mumbai) about how teaching street children music could give them a different way out of poverty. At that point, neither of us had any idea that such music projects existed anywhere. We were not actively thinking or talking about it, and we soon forgot about it.

This changed later that year. The BBC Proms—the UK’s largest classical music festival—had not one but two large orchestras drawn specifically from the demographic we had been thinking of earlier that year. Here they were, two professional orchestras from Venezuela and South Africa, performing on the world’s biggest stage for classical music. Through our research, we learnt of similar projects around the world—across South America, and in the USA, Europe, and the UK.

At the Buskaid South Africa Proms, when we bumped into some of the young players fooling around in Hyde Park, one of them said, “Music saved my life.” He explained that he could have been drawn into drugs or crime like many of his peers, but music lessons kept him away from those dangers. The violin in his hand had kept him alive, literally.

After that, things began to snowball. We began looking up existing projects, and writing to people involved in them. Then, before we knew it, we were talking to other musicians in the UK, someone offered us a promise of a grant to start, and lots of connections were made. In July 2008, we were back in Goa, which was home to Luis. I was two months pregnant, still reeling from a miscarriage the previous Christmas.

The rest, as they say, is history. We formed Child’s Play India Foundation in 2009 “to provide positive values and social empowerment to India’s disadvantaged children through the teaching of classical music to the highest possible standard”. It took months of talking to lawyers and dealing with legalese and paperwork, something that has now defined my life. But we knew music could make a difference, and change lives. With the launch of the Symphony Orchestra of India in 2006, the country’s only professional orchestra based at the NCPA in Mumbai, the timing of our launch seemed fortuitous.

In early 2010, we found a willing partner in late Mangala Wagle, who had set up Hamara School—a shelter in Goa for children of construction workers, balloon sellers, prisoners, ragpickers, or anyone who needed a safe place to live and study. The shelter pays for mainstream school education, offers meals, after-school help with studies, and hostel facilities. We would provide free classes in western classical music to any interested child.

The question remained though: What impact could Beethoven, Bach, or Mozart have on such traumatised lives?

Turns out, quite a lot.

It seemed like a mad experiment when we started. People were bemused by the project. Giving violins to children of construction workers, balloon sellers, and prisoners? Why focus on them, it is not ‘their’ music, we were told. Our response was that Mozart was as much theirs as it was our son’s. Everyone deserves the opportunity to learn new things, to enjoy an art form that children around the world have the opportunity to immerse themselves into. Plus, learning western classical music often opens new doors in education and employment. Studies have repeatedly shown the connection between learning music and the impact it has on a child’s brain and development.

We hired a local violin teacher to come by and teach at Hamara School in the St. Inez suburb of Panjim, Goa’s capital. On Day one, 15 or so curious children turned up. It was chaotic, but soon a structure emerged. Miraculously, the kids kept turning up for class. We had to divide them into batches to accommodate them all. Instruments were donated, some were purchased. We slowly introduced other instruments—cello, recorder, and flute. For years we held classes at the children’s shelter, in the same rooms where the kids study, play, eat, and sleep. On good weather days, we practiced outside in the courtyard. A crowd would gather on the other side of the fence to watch.

Every Child Deserves Opportunities

Fourteen years is a long time to watch a child grow. Some of the children who began classes in 2010 are still with us. Some are now teenagers, others almost on the cusp of adulthood. All of these young people are not only continuing to study music, but they are doing exceptionally well in their academics as well. One of our students, who has been with us from the beginning, is now studying to be a chartered accountant. One of our violin students recently scored 91 per cent in the 10th standard Goa Board Exam, and has secured admission into the science stream in the college of her choice. Others are preparing for bank exams.

These children’s family background is fraught and difficult. They juggle stress levels beyond anything we may deal with.

It took us some time to clarify in our own minds that these pressures should be taken into consideration when lessons are missed, or practice foregone.

The work has to be done, but empathy is important if we want to engage with these students, and understand what they are going through. They have to study (some are first-generation learners), deal with financial strain, and often, alcoholic parents. Many of our students can’t take instruments home, where they may be stolen, damaged, or worse, used as a weapon. For these students, we ask them to leave their instruments at our office; they are welcome to come any day to practice.

In India, marginalised children have to fight so many battles. The poverty of their parents is a huge stumbling block, as are the obstacles of caste and access to education and employment. We want to give these children a fighting chance. Not all of the children in our project will become orchestral musicians. Not all of them will continue to learn music. Some drop out, losing interest. Others move away, and can’t continue with lessons. Girls are especially vulnerable to being pressured into early marriages, or dropping out from school to work to supplement the family’s income, perform household chores, or care for younger siblings.

Whatever their circumstances, we feel that learning music shows our students that there is another world out there. It is a world of possibility, of beauty and hope. Our advanced students are offered a part-time paid position as trainee teachers working with beginners, empowering them to think beyond traditional means of earning an income.

People often ask me what the most difficult part of running a music charity is. Is it funding? Is it finding the children, or partners to work with? Funding is always an issue, but every time we have needed money, or had to purchase an instrument (or twenty), donors have come forth serendipitously. Friends, family, Facebook acquaintances, and people who attend our concerts have supported us. There have even been people who have passed by on the other side of the fence, so impressed by what they heard and saw that they wanted to be involved. I find that tremendously moving. Social media posts can only tell you part of a story, but when you see it in action at concerts or in situ, that’s when the penny drops. That’s when it clicks.

Even after all these years, people still ask us: can music be transformative? Can children who have had zero exposure to classical music learn Beethoven? Can “those” children even appreciate Bach? The hurdles were many. Explaining the vision of the project in itself to those who were used to seeing only privileged kids learning music was an uphill task.

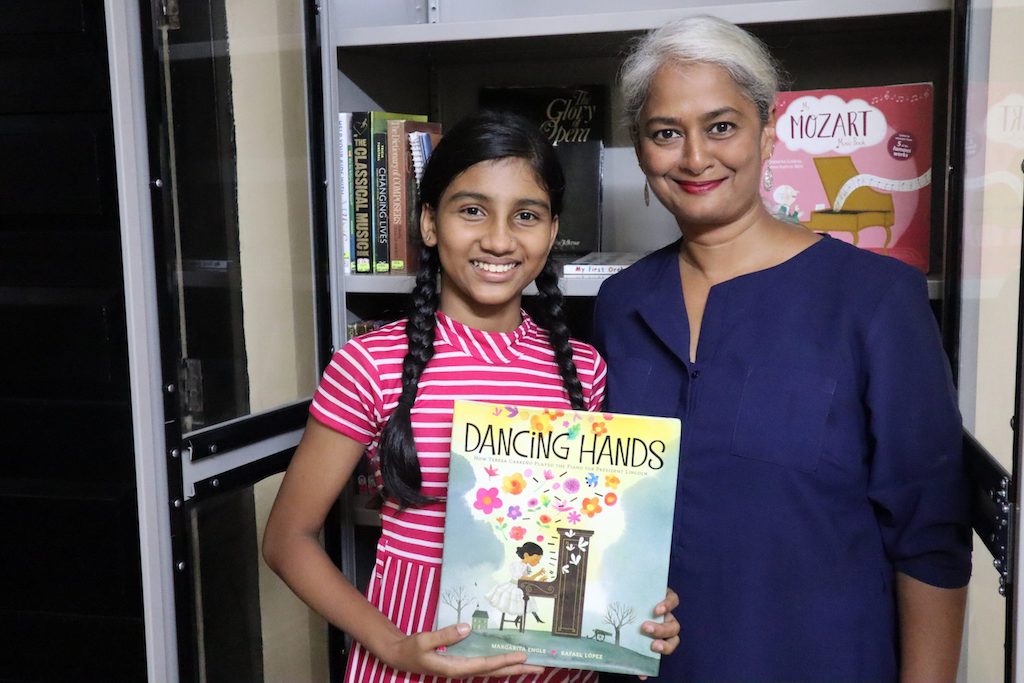

At Child’s Play India Foundation, we do everything possible to ensure that every opportunity is given to our students. For many, this world of classical music is indeed alien. So we show them films, and share YouTube links for them to watch. We have just opened a library of beautiful, easy-to-read books about music that will hopefully show them what a big, vibrant world of music is out there, waiting for them to reach out.

Once, after the summer holidays, we had a surprise ‘welcome back’ party where every child received a soft toy to take home. Some of the children told me that it was the first soft toy they ever called their own. This brought tears to my eyes. It’s one more thing we take for granted.

Just like the welcome-back party, we’ve had other opportunities to engage with our students in a personal way. Every year, after our annual Christmas concert, we take them for a thank-you lunch at a restaurant, or space with a play area. It gives us a chance to interact with them in a non-class setting which is liberating in many ways. We also celebrate milestones like big birthdays, and excellent academic results.

A few years ago, I began collecting all the photos we take of the students, and printing them out annually to give it to them as keepsakes. For many of them, these are the only childhood photos they will have. With smartphones now becoming ubiquitous, perhaps this is now redundant, but hard copies of photos are still unusual enough to be a treat.

Music education is not just about learning instruments and playing harmoniously in an orchestra, although that is important. It’s about building good humans, good citizens. Playing in an orchestra teaches discipline and teamwork. To our students, it gives the opportunity to be seated as equals with their peers. In the orchestra, we don’t care about your family background, your surname, or how you dress. The only criteria is whether you’ve put in the work, and can play to the standard required.

As the covid-19 pandemic waned and we restarted classes last year, one of our quietest students came up to Luis and spoke about how she had missed playing music very much during the lockdowns. This student has had a traumatic childhood and involving her in music lessons was initially a way of distracting her from her pain. Today, she’s one of our most promising students. Whether this young girl becomes a musician or not is secondary. What matters is that we were able to give her something to love, something that brings her joy.

It’s our fifteenth anniversary next year. We want to reach out to many more marginalised children. I have lots of ideas for new projects and collaborations, but our biggest stumbling block is teachers. We need qualified and experienced teachers for strings and choir.

We would love to have a full complement of woodwinds and brass as well, but without a steady supply of teachers, the instruments are too expensive to invest in. Online teaching hasn’t worked for us, so teachers need to be based in Goa. In the past decade, we have had some wonderful teachers from all over the world, and we continue to welcome musicians who want to come to Goa and change a child’s life. Because, as our tagline says, every child is ‘note’worthy.

This article first appeared on Dark ‘n’ Light.