Beethoven’s Greatest Works and the Stories Behind Them

Beethoven’s music continues to inspire and challenge listeners centuries later. From the heroic “Eroica” to the transcendent Ninth Symphony, his greatest works reveal the struggles, passions, and triumphs that shaped one of history’s most enduring composers.

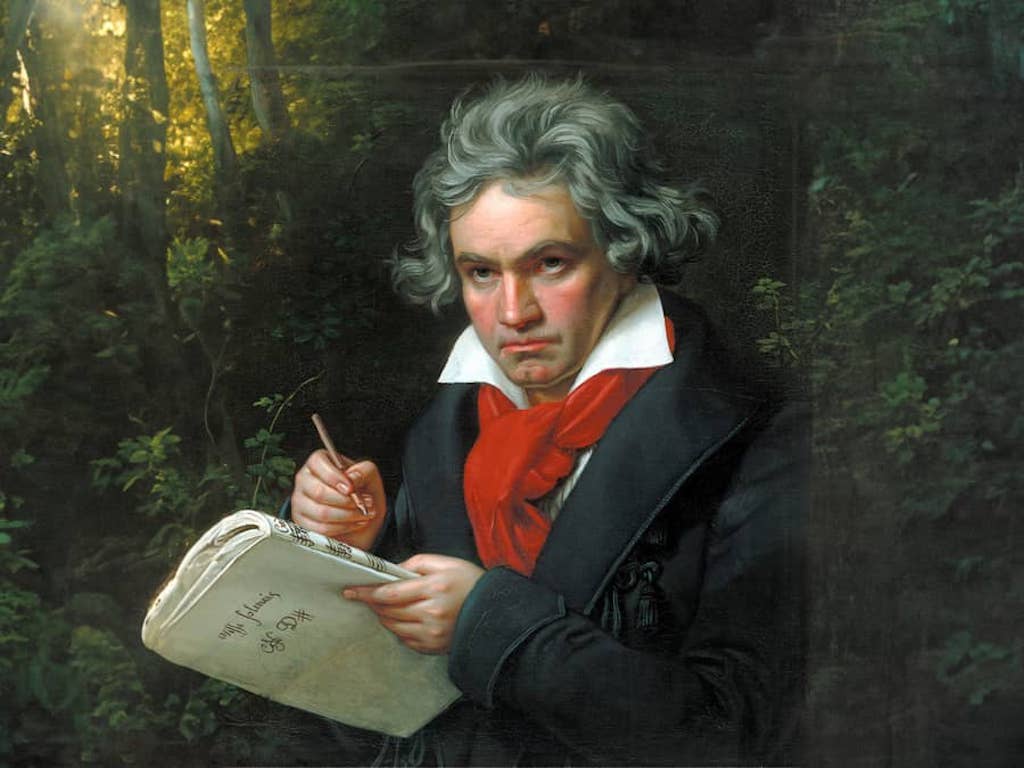

Few names in the history of music resonate as powerfully as Ludwig van Beethoven. The German composer, born in Bonn in 1770 and later settled in Vienna, remains a towering figure whose works have defined and redefined the very notion of Western classical music. Beethoven’s music has become synonymous with struggle, triumph, and human spirit. It speaks across centuries, often revealing not only his personal battles but also the cultural and political tensions of his time.

In this article we look at some of Beethoven’s greatest works and the fascinating stories behind them, from his groundbreaking symphonies to his intimate chamber music and monumental piano sonatas.

Symphony No. 3 in E-flat major, Op. 55, “Eroica”

When Beethoven premiered his Third Symphony in 1804, audiences were bewildered. The work was far longer, more ambitious, and more emotionally intense than anything heard before. What had traditionally been a stately four-movement form had now become an arena for drama and conflict.

Beethoven initially dedicated the symphony to Napoleon Bonaparte, whom he admired as a symbol of revolutionary ideals. Yet when Napoleon crowned himself Emperor, betraying those republican principles, Beethoven flew into a rage and tore the dedication page. He is reported to have shouted that Napoleon was nothing more than an ordinary tyrant.

The “Eroica” thus became more than a tribute. It was a statement about heroism in the abstract, a symphonic monument to human courage. Its funeral march in the second movement is among the most powerful ever written, expressing grief and grandeur in equal measure. Today the work stands as the turning point where the Classical era gave way to the Romantic, expanding the boundaries of what a symphony could be.

Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67

Perhaps no piece of music is more instantly recognisable than the opening motif of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony: four notes that seem to hammer on the door of fate itself. Premiered in 1808 in a freezing Vienna concert hall, the work quickly became emblematic of human struggle against adversity.

The story behind those four notes has been subject to much speculation. Beethoven’s pupil and secretary Anton Schindler claimed that the composer described them as “fate knocking at the door”. Although Schindler’s reliability is often questioned, the idea has stuck and the music itself seems to confirm it.

Beethoven was at this time grappling with increasing deafness and personal isolation. The symphony moves from the stormy and relentless C minor of the first movement to a triumphant C major finale, complete with piccolo, trombones and contrabassoon, instruments rarely used in symphonies of the time. It is a journey from darkness into light, often interpreted as a metaphor for resilience and victory.

Piano Sonata No. 14 in C-sharp minor, Op. 27 No. 2, “Moonlight”

The “Moonlight Sonata” is perhaps Beethoven’s most beloved piano work, and its story is as intriguing as its music. Written in 1801 and dedicated to Countess Giulietta Guicciardi, a young aristocrat with whom Beethoven was briefly infatuated, the work was not originally titled “Moonlight” at all. That name was coined years later by the critic Ludwig Rellstab, who said the first movement reminded him of moonlight shining upon Lake Lucerne.

The sonata departs from convention by placing the slow, brooding movement at the beginning instead of in the middle. Its gentle arpeggios create an atmosphere of intimate melancholy, while the turbulent final movement bursts forth with stormy passion. The work reflects Beethoven’s ability to convey deep emotion through simplicity, and it has remained a staple of piano repertoire ever since.

Behind its beauty lies Beethoven’s longing and frustration, both artistic and personal. Although he admired Giulietta, their difference in social class meant marriage was impossible. The piece thus captures a mix of yearning and despair that gives it its enduring poignancy.

Symphony No. 6 in F major, Op. 68, “Pastoral”

Not all of Beethoven’s music was about storm and struggle. The “Pastoral” Symphony, premiered alongside the Fifth in 1808, celebrates the composer’s love of nature. Beethoven was known for his long walks in the countryside around Vienna, where he felt at peace and often carried sketchbooks to jot down musical ideas.

The symphony paints a vivid picture of rural life. Its five movements include depictions of a flowing brook, a merry gathering of peasants, a thunderstorm, and a shepherd’s song of thanksgiving. Rather than using literal imitations, Beethoven evoked the spirit of the countryside, blending lyrical melodies and rhythmic patterns that suggest natural sounds.

In contrast to the monumental heroism of the Fifth Symphony, the “Pastoral” offers serenity, joy, and a sense of unity with the natural world. It demonstrates Beethoven’s extraordinary range, showing how he could communicate both personal struggle and pastoral tranquillity with equal mastery.

Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61

When first performed in 1806, Beethoven’s Violin Concerto puzzled audiences. The work’s length and complexity seemed excessive compared to other concertos of the time. Yet it has since become one of the greatest violin concertos ever written.

The story behind its creation involves Beethoven’s friendship with the virtuoso violinist Franz Clement. Clement reportedly sight-read much of the concerto at the premiere, which might explain why critics at first found it uneven. However, the concerto’s lyrical beauty and expansive scale later won admirers, thanks in part to a revival by Joseph Joachim under the baton of Felix Mendelssohn in 1844.

The slow movement in particular shows Beethoven at his most tender, with delicate dialogues between soloist and orchestra. The finale, full of rhythmic vitality, brings the work to a spirited close. Today it is considered the pinnacle of the violin repertoire, demanding not just virtuosity but profound musicality.

Missa Solemnis in D major, Op. 123

Beethoven’s religious beliefs were complex, yet his Missa Solemnis, completed in 1823, remains one of the greatest sacred works ever written. He described it as his “greatest work”, though it was rarely performed in his lifetime due to its scale and difficulty.

The Mass was intended for the enthronement of Archduke Rudolph, Beethoven’s patron and pupil, as Archbishop of Olmütz. However, Beethoven missed the deadline, and the piece took years to complete. The result was not simply liturgical music but a profound expression of spiritual yearning.

With its massive choruses, intricate fugues, and orchestral grandeur, the Missa Solemnis pushes performers to their limits. The “Agnus Dei” ends with a plea for peace, written in a Europe still scarred by the Napoleonic wars. For Beethoven, whose deafness was by then almost total, the work represented a deeply personal dialogue with faith, doubt, and humanity.

Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125, “Choral”

Beethoven’s final symphony, premiered in 1824, is perhaps the most celebrated of all. It broke every boundary of the symphonic form by introducing voices in the last movement, setting Friedrich Schiller’s “Ode to Joy” to music. The idea of universal brotherhood expressed in the text gave the symphony a resonance that has transcended its time.

The premiere was a historic event. Beethoven, completely deaf, stood on stage to conduct the orchestra but was unable to hear the applause. One of the soloists had to turn him around to face the audience so he could see the ovation. Witnesses described the scene as one of the most moving in musical history.

The Ninth Symphony has since become a symbol of unity, freedom, and shared humanity. It has been performed at pivotal moments in history, from the fall of the Berlin Wall to Olympic Games ceremonies. Its combination of musical grandeur and philosophical vision places it among the greatest achievements of art.

String Quartet No. 14 in C-sharp minor, Op. 131

Late in his life, Beethoven turned increasingly towards chamber music, producing a series of string quartets that baffled his contemporaries but are now regarded as profound masterpieces. The Quartet in C-sharp minor, Op. 131, written in 1826, is especially remarkable.

The work unfolds in seven continuous movements, a radical departure from convention. Its opening fugue is solemn and introspective, followed by movements of varied character ranging from playful dance to heart-rending lyricism. Schubert, shortly before his death, is said to have remarked that after hearing this quartet, he felt overwhelmed by its depth and beauty.

These late quartets reflect Beethoven’s inner world at a time when he was isolated by deafness, poor health, and personal difficulties. Yet they also reveal a transcendence that seems to go beyond earthly concerns. Many musicians consider them the pinnacle of the quartet repertoire, and Op. 131 in particular has inspired countless composers from Wagner to Bartók.

Conclusion

Beethoven’s greatest works are not merely pieces of music but windows into a soul that grappled with adversity, passion, and vision. From the heroic spirit of the “Eroica” to the cosmic reach of the Ninth Symphony and the intimate revelations of the late quartets, each composition carries a story that enriches our understanding of the man and his era. His struggles with deafness, his turbulent personal relationships, and his engagement with the political upheavals of his time all found their way into his art. Yet Beethoven’s music does more than reflect his own life. It speaks to universal human themes of struggle, joy, despair, faith, and triumph.