Bach’s other Passion, the earlier

Celebrating the end of Christ’s life in his two extant Passions this is his first major choral work for Leipzig, Bach being only recently employed there as Cantor.The two existing Passions distill the same story with Jesus rising from the dead on Easter Sunday morning. But before this is the gruelling tale of the Passion ending with the crucifixion of Christ on the cross along with two thieves. Bach sets chapters 26 and 27 from Matthew’s and 18 and 19 from John’s.It is almost 300 years since Bach composed this highly dramatic setting of the Passion story. His complex masterpiece, a mixture of the sacred and the theatrical, is based on Chapters 18 and 19 of the Gospel of St John.

While the tenor Evangelist narrates the story, the other soloists and the choir portray Jesus Christ and the wide variety of characters whose combined actions led inexorably to his death. Bach intersperses intense and often vicious crowd scenes with devotional arias and chorales encouraging his Lutheran congregation to acknowledge their own responsibility for the death of Jesus, which their sins had made necessary. The work ends with choruses in praise of Christ as risen Lord and King.

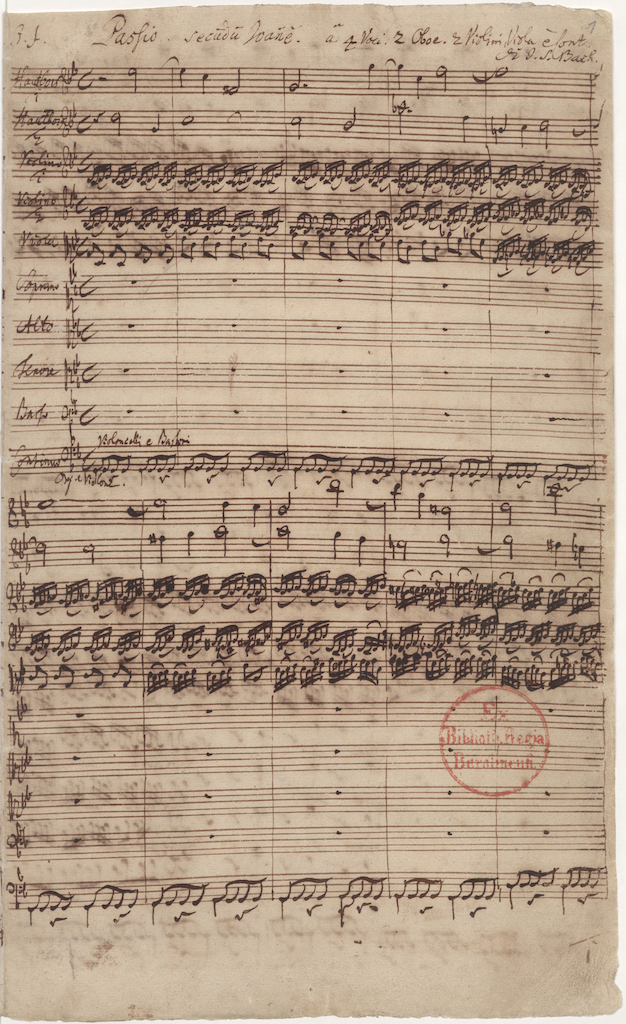

Bach’s first years in Leipzig were remarkable for his prodigious production of cantatas for the Sundays and holidays of the Lutheran liturgical cycle. In the 12 months from May 1723 at least 50 works were performed, nearly all of which were newly composed. The musical highpoint of the year was Vespers on Good Friday, when a Passion oratorio, with a sermon between Parts One and Two, was given. That form had come late to Leipzig, the first performance having taken place in 1717. Bach’s predecessor as Cantor wrote a St Mark Passion for the Thomaskirche in 1721. Three years later, on April 7th, 1724, the new man presented his St John Passion. It was not his first essay in this field. The official Obituary speaks of five Passions, believed to have been written between 1717 and 1731, but only two are known to have survived – the other being the St Matthew Passion of 1727.

For his first Leipzig Passion Bach had booklets printed, saying it would take place in the Thomaskirche. The town council, his employers, reminded him it was the turn of the Nikolaikirche to stage the event. Bach protested that there was not enough room for the musicians. The council stuck to its guns but paid for a flyer announcing the correct venue and provided sufficient performing space. It was the first of many confrontations between Cantor and municipality. First, St John’s account of the Passion is not as varied scenically as St Matthew’s – for example it does not have the Last Supper or the Agony in the Garden. Second, whereas by 1727 the poet Picander had supplied a tailor-made libretto for the arias and reflective choruses of the St Matthew Passion, when Bach composed the St John Passion he had to adapt passages for these from several authors, in particular the poet and Hamburg councillor Brockes.

The first Leipzig Passion has a different balance between Gospel verses and poetic meditation from that of the second; however, whether or not Bach was making a virtue out of necessity, the absence of solo arias during the central trial scene adds considerably to its impact. And, as so often, Bach took an existing genre and raised it immeasurably in terms of dramatic power, orchestral colour and richness of harmony and counterpoint.

The Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment is a premier original instruments and performance practice ensemble from the UK. On April 6th 2022, under the able direction of Mark Padmore, he and his instrumental and vocal forces paid tribute to the great Leipzig composer at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées. Although smaller in scale and length than the more popular St Matthew Passion, hearing the two in close proximity of within a week leading up to the good Friday bank holiday weekend was a very special pleasure. The evangelist himself, in this case St John, was sung by tenor Mark Padmore while leading the instrumental and choral ensemble himself. This is a mammoth task to which he rose admirably. Also very fulfilling was the bass Raoul Stefano as Jesus Christ. All the arias and chorales were convincingly sung keeping in mind historically informed performance practice. The star of the evening was the orchestra - a coherent and cohesive band of some two and a half dozen musicians clustered towards the left of the stage with some 10 or 12 singers to the right. Early instruments like the oboe d’amore and viola da gamba were a welcome sight in the orchestra with very rare pitching or tuning problems. I was very fortunate to catch this exceptional performance in Paris as part of the tour from London’s Queen Elizabeth Hall to Brussels, Amsterdam and Utrecht via Paris.