Bach’s Holy Dread

The composer has long been seen as a symbol of divine order. But his music has an unruly obsession with God.

“O Lord, our Lord, how excellent is thy name in all the earth!” The words of the Psalm look bright on the page, but the music pulls them into shadow. The key is G minor. The bass instruments drone on the tonic while the violins weave sixteenth notes around the other notes of the triad. On the third beat of the first bar comes a twinge of harmonic pain—one oboe sounding an E-flat against another oboe’s held D. Oboes are piercing by nature; to place them a half step apart triggers an aggressive acoustic roughness, as when car horns lean on adjacent pitches. In the next several bars, more dissonances accumulate, sustaining tension: F-sharp against G, A-flat against G, E-flat against D, B-flat against A-natural. The ensemble wanders away from the home key and then back, whereupon the cycle begins again, now with a chorus singing “Herr, unser Herrscher” (“Lord, our ruler”) in chords that contract inward:

Herr!

Herr!

Herr!

unser

Herr-r-r . . .

When the upper voices reach “Herrscher,” they dissolve into the swirl of the violins, the first syllable elongated into a thirty-three-note melisma. You need not have seen the words Passio secundum Johannem at the head of the score to feel that this is the scene at Golgotha: an emaciated body raised on the Cross, nails being driven in one by one, blood trickling down, a murmuring crowd below. It goes on for nine or ten minutes, in an irresistible sombre rhythm, a dance of death that all must join.

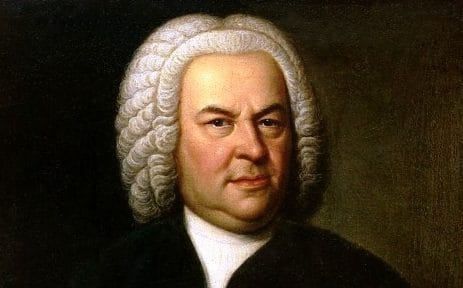

What went through the minds of the congregation at the Nikolaikirche, in Leipzig, on Good Friday, 1724, when the St. John Passion had its first performance? A year earlier, Johann Sebastian Bach, aged thirty-nine, had taken up posts as the cantor of the St. Thomas School and the director of music for Leipzig’s Lutheran churches. He had already acquired a reputation for being difficult, for using “curious variations” and “strange tones.” More than a few of his works begin with gestures that inspire awe and fear. Several pieces from his years as an organ virtuoso practice a kind of sonic terrorism. The Fantasia and Fugue in G Minor feasts on dissonance with almost diabolical glee, perpetrating one of the most violent harmonies of the pre-Wagnerian era: a chord in which a D clashes with both a C-sharp and an E-flat, resulting in a full-throated acoustical scream.In the St. John Passion, Bach’s art of holy dread assumes unprecedented dimensions. The almost outlandish thing about “Herr, unser Herrscher” is that it does not simply take the point of view of the mourners and the mockers. It also adopts the perspective of the man on the Cross, gazing up and down. Aspects of the music that seem catastrophic acquire a triumphant tinge. The rhythm conveys mysterious vitality: the second time the “Herr!” chords sound, they fall on the second and fourth beats of the bar, in a kind of cosmic syncopation. A single note is lobbed from one section of the ensemble to another, giving a sense of ever-widening space. The sixteenth notes in the violins unspool almost continuously, suggesting the transmission of the Lord’s name through all lands. In the second section of the chorus, where words from Psalm 8 give way to a meditation on the Crucifixion, the dissonances dwindle, and the music moves through a series of expectant dominant-seventh chords, describing a methodical ascent:

Show us, through Your Passion,

That You, the true Son of God,

Through all time,

Even in the greatest humiliation [Niedrigkeit],

Have become glorified [verherrlicht]!

The words Niedrigkeit and verherrlicht land side by side. With the second, Bach writes “forte” in the score, and stamping, defiant D minor takes over. The contradiction of the opening is overcome: light and dark are one.

The conductor John Eliot Gardiner has called “Herr, unser Herrscher” a “portrayal of Christ in majesty like some colossal Byzantine mosaic . . . looking down on the maelstrom of distressed unregenerate humanity.” Others have seen it as a picture of the Trinity, with the pedal point of the Father, the suffering discord of the Son, and the shimmering motion of the Holy Spirit. Whatever images come to mind, the craft that went into the making of the scene—the melodic inspiration, the contrapuntal rigor, the immaculate demonstration of the rules, the insolent breaking of them—is as astounding now as it must have been on that day in 1724. Or so we like to think. One notable fact about the St. John Passion—and about its successor, the St. Matthew—is that we have no eyewitness account of the première. If the good people of Leipzig understood that they were in the presence of the most stupendous talent in musical history, they gave no sign. Indeed, Bach removed “Herr, unser Herrscher” from the score when he revived the St. John the following year—a hint that his listeners may have gone away unhappy.

“Bach & God” (Oxford) is the splendid title of a new book by Michael Marissen, a professor emeritus at Swarthmore College. It brings to mind two approximately equal figures engaged in a complicated dialogue, like Jefferson and Adams, or Siskel and Ebert. The book is one of a number of recent attempts to grapple with Bach’s religiosity. Others are Gardiner’s “Bach: Music in the Castle of Heaven” (Knopf); Eric Chafe’s “J. S. Bach’s Johannine Theology” (Oxford); and John Butt’s “Bach’s Dialogue with Modernity: Perspectives on the Passions” (Cambridge). All ask, in different ways, how we should approach works whose devotional intensity is alien to most modern listeners. Marissen identifies himself as an agnostic, but adds that in the vicinity of Bach’s music he will never be a “comfortable agnostic.”

Previous Bach scholarship tended to take a more secular tack. Many of us grew up with an Enlightenment Bach, a nondenominational divinity of mathematical radiance. Glenn Gould’s commentary on the “Goldberg Variations” spoke of a “fundamental coordinating intelligence.” One German scholar went so far as to question the sincerity of Bach’s religious convictions. But the historically informed performance movement, in trying to replicate the conditions in which Bach’s works were first played, helped to restore awareness of his firm theological grounding. Recorded surveys of the two hundred or so sacred cantatas, including Gardiner’s epic undertaking in 1999 and 2000, have brought Bach’s spirituality to the forefront. To what extent does he faithfully transmit Lutheran doctrine? What did he privately believe? Marissen also confronts an issue that many prefer to avoid: do Bach’s Passions project anti-Semitism?

Such questions run up against the central agony of writing about Bach: the paucity of biographical information. Gardiner writes, “We seem to know less about his private life than about that of any other major composer of the last 400 years.” Bach left few substantial traces of his inner life. Mostly, we have a stack of notoriously dull, grouchy business correspondence. The composer-comedian Peter Schickele, better known as P. D. Q. Bach, captured the conundrum in his “Bach Portrait,” of 1989, which juxtaposes bombastic orchestral utterances in the mode of Copland’s “Lincoln Portrait” with recitations from “The Bach Reader”: “My present post amounts to about seven hundred thaler, and when there are rather more funerals than usual, the fees rise in proportion.”

Gardiner’s book, a vividly written volume that appeared in 2013, tries to fill in some of the gaps. We see Bach emerging from a society still traumatized by the Thirty Years’ War and by outbreaks of plague. Life expectancy was around thirty. In the Thuringian town of Eisenach, where Bach was born, quasi-pagan notions of devilry still prevailed. Bach’s education would have been doctrinaire and reactionary. “History is nothing but the demonstration of Christian truth,” one popular textbook said. Gardiner highlights German research that notes rampant ruffianism among Eisenach’s youth and a troubling trend of “brutalization of the boys.” Gardiner may go too far in characterizing Bach as a “reformed teenage thug,” but the young composer is known to have drawn a dagger in the midst of an altercation with a bassoonist.

Thuggish or not, Bach immersed himself in music at an early age, as had generations of Bachs before him. An obituary prepared by Bach’s son Carl Philipp Emanuel speaks of his father’s “unheard-of zeal in studying.” That claim is buttressed by a discovery made a decade ago, of the teen-aged Bach’s precociously precise copies of organ pieces by Reincken and Buxtehude. His life was destined to unfold in a constricted area. The towns and cities where he spent his career—Arnstadt, Mühlhausen, Weimar, Cöthen, and Leipzig—can be seen in a few hours’ driving around central and eastern Germany. But his lifelong habit of studying and copying scores allowed him to roam the Europe of the mind. In his later years, he copied everything from a Renaissance mass by Palestrina to the up-to-date Italianate lyricism of Pergolesi. Bach became an absolute master of his art by never ceasing to be a student of it.

His most exalted sacred works—the two extant Passions, from the seventeen-twenties, and the Mass in B Minor, completed not long before his death, in 1750—are feats of synthesis, mobilizing secular devices to spiritual ends. They are rooted in archaic chants, hymns, and chorales. They honor, with consummate skill, the scholastic discipline of canon and fugue. They make expert use of the word-painting techniques of the Renaissance madrigal and Baroque opera. They absorb such stock scenes as the lament, the pastoral, the lullaby, the rage aria, the tempest. They allude to courtly French dances, Italian love songs, the polonaise. Their furious development of brief motifs anticipates Beethoven, who worshipped Bach when he was young. And their most daring harmonic adventures—for example, the otherworldly modulations in the “Confiteor” of the B-Minor Mass—look ahead to Wagner, even to Schoenberg.

They are works of deep devotion but also of high ambition. Before Bach went to Leipzig, in 1723, he had been contentedly ensconced in Cöthen, some forty miles to the northwest, where a music-loving prince elicited such instrumental tours de force as the first book of the “Well-Tempered Clavier,” the English Suites, and the music for solo violin and solo cello. But the prince was a Calvinist, and had little need of sacred music. Bach evidently saw the Leipzig job as an opportunity to shape the spiritual life of a city. For the first few years, he pursued that project with ferocious energy, composing cantatas on a weekly basis. Gardiner plausibly evokes Bach in his studio, copyists around him, cranking out music at a frenzied pace—a picture “not dissimilar to the backstage activities on a TV or film set.”

For the most part, Leipzig failed to appreciate the effort. Bach was reprimanded for neglecting his teaching duties and for inserting himself into musical and liturgical matters around the city. A member of the town council called him “incorrigible.” The extensive revisions that he made to the St. John Passion in 1725—“Herr, unser Herrscher” was not the only striking section of the score to be cut—were possibly the result of outside interference. The judgment of another composer in 1737 may sum up the conventional wisdom in Leipzig: “This great man would be the admiration of whole nations if he had more agreeableness, if he did not take away the natural element in his pieces by giving them a turgid and confused style, and if he did not darken their beauty by an excess of art.” Bach, for his part, complained in a letter that his experience had been one of “almost continual vexation, envy, and persecution.” Attempts to find a position elsewhere fell short, however, and he remained in Leipzig until his death.

He became a distinguished figure in his final years, his influence felt in many corners of German music, not least because of the activity of his various composing sons. He received the title of Court Composer from the Elector of Saxony and, on a visit to Berlin, astonished Frederick the Great with his improvisations. Still, he had nothing like the celebrity of his contemporary Handel. According to Carl Philipp Emanuel, Bach twice tried to arrange a meeting with Handel, but the latter contrived to make himself unavailable. The implication is that Handel felt threatened. The anecdote gives a poignant glimpse of Bach’s personality: he yearned to join the international élite, but the trappings of success were denied him. He made careful copies of the Passions in his last years, which suggests a hope for posthumous vindication, but he could hardly have imagined the repertory culture that came into existence in the nineteenth century. More likely, he simply wanted to prevent his music from vanishing. Some of it did: at least one other Passion, after St. Mark, was lost.

The book that perhaps reveals more of Bach than any other can be found at the Concordia Seminary, in St. Louis. By chance, that organization came into possession of Bach’s copy of Abraham Calov’s three-volume edition of the Bible, which contains Luther’s translation of the Bible alongside commentaries by Luther and Calov. Bach made notes in it and, in 1733, signed his name on the title page of each volume. The marginalia establish the fervor of his belief: no Sunday Christian could have made such acute observations. Bach singles out passages describing music as a vessel of divinity: in one note, he observes that music was “especially ordered by God’s spirit through David,” and in another he writes, “With devotional music, God is always present in his grace.” The annotations also seem to reveal some soul-searching. This passage is marked as important, and is partly underlined: “As far as your person is concerned, you must not get angry with anyone regardless of the injury he may have done to you. But, where your office requires it, there you must get angry.” One can picture Bach struggling to determine whether his “almost continual vexation” stemmed from his person or his office—from vanity or duty.

Yes, Bach believed in God. What is harder to pin down is how he positioned himself among the theological trends of the time. The Pietist movement, which arose in the late seventeenth century, aimed at reinvigorating an orthodox Lutheran establishment that, in its view, had become too rigid. Pietists urged a renewal of personal devotion and a less combative attitude toward rival religious systems, including Judaism. Bach made passing contact with Pietist figures and themes, though he remained aligned with the orthodox wing—not least because Pietists held that music had too prominent a role in church services.

Bach’s two surviving Passions point to an older doctrinal split. John is the visionary among the Evangelists, his philosophical grandeur evident from the first verse (“In the beginning was the Word”). As Chafe observes, the St. John Passion stresses Jesus’ messianic nature and accentuates oppositions between good and evil. Theologians relate John to the “Christus Victor” conception of Atonement, which dates back to Christianity’s early days, and according to which Christ died on the Cross knowing that his Resurrection would redeem mankind. In Matthew, Jesus has less foreknowledge: “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” Matthew accords with the other major conception of Atonement, known as the “satisfaction theory,” in which humanity is redeemed through the sacrifice of an utterly blameless person. The opening chorus of the St. Matthew Passion, “Kommt, ihr Töchter, helft mir klagen” (“Come, you daughters, help me mourn”), is an engulfing river of lament, lacking the triumphalism of “Herr, unser Herrscher.” The St. Matthew is the more openhearted, empathetic work; the St. John remains a little frightening.

Chafe’s interpretation of the St. John detects theology in almost every bar. He notes that over the two parts of the Passion—the first centered on Peter’s denial of Jesus, the second on Jesus’ trial before Pontius Pilate—Bach shifts from flat key signatures to sharp ones and back again. The very look of the notation on the page might be symbolic: sharp signs resemble crosses (# or x). At each transition, Jesus’ seeming defeat becomes an emblem of his power. After all, he had predicted that Peter would deny knowing him, and so that humiliation only leads to his victory. Before Pilate, Jesus exposes the emptiness of earthly authority. (“You would have no power over Me, if it were not given to you from above.”) As this exchange takes place, the tonality is yanked from D minor, with one flat, to C-sharp minor, with four sharps. Much of Chafe’s analysis is arcane, in places straining credulity; but Bach, too, was a man of arcane bent.

Marissen’s readings are similarly eagle-eyed, but he is on the lookout for a grimmer strain in Lutheranism. Luther’s ugliest legacy was the invective that, in his later years, he heaped on the Jewish people. His 1543 treatise “On the Jews and Their Lies” calls for the burning of synagogues and Jewish homes. “We are even at fault for not striking them dead,” Luther writes. Other writings endorse the blood libel—the legend that Jews kill Christian children for ritual purposes. Such sentiments were echoed by the more strident theologians of Bach’s time. One was the Hamburg pastor and poet Erdmann Neumeister. In 1720, Bach was under consideration to become the organist at Neumeister’s church, and five of his cantatas set Neumeister texts. (The pastor helped to invent the cantata as Bach practiced it: a suite of recitatives, arias, and choruses on a religious topic.)

Other Lutheran theologians, particularly those in the Pietist camp, were considerably more tolerant. The musicologist Raymond Erickson has highlighted a document known as theGutachten, published in Leipzig in 1714, which denounces the blood libel as baseless. A Pietist named August Hermann Francke—who, according to Chafe, may have influenced the themes of the St. John Passion—advocated the conversion of Jews to Christianity, but did so in a spirit of persuasion rather than coercion. Francke also deëmphasized the idea that the Jews were primarily or solely to blame for Christ’s death. He wrote, “Blame yourself, O humankind, whether of the Jews or the Gentiles. . . . Not only Caiaphas and Pilate, but I myself am the murderer.” To be sure, Luther said much the same in a 1519 sermon on the Crucifixion. The vituperation of his later writings can be balanced against earlier, more generous judgments. Such were the tensions that existed in Bach’s world on the question of the Jews.

The most troubling of the cantatas is “Schauet doch und sehet” (“Behold and see”), which Bach composed during his first year in Leipzig. It meditates on the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 A.D. In Lutheran culture, Marissen says, the fall of Jerusalem was thought to represent “God’s punishment of Old Jerusalem for its sin of rejecting Jesus.” Calov quotes Luther to the effect that contemporary Jews are “children of whoredom” who must “perish eternally.” Unfortunately, it’s clear that Bach paid attention to such passages. At one point, Calov notes that in the wake of Jerusalem’s destruction Jews have had to experience “the same sort of thing for over 1600 years, even to this day.” Marissen observes that under “1600” Bach wrote “1700.” This pedantic updating hardly indicates dissent.Anti-Jewish rancor is carried over into the text of “Schauet doch.” A tenor sings:

Let whole rivers of tears flow,

Because there has befallen you an irreparable loss

Of the Most High’s favor . . . .

You were handled like Gomorrah,

Though not actually annihilated.

Oh, better that you were utterly destroyed

Than that one at present hears Christ’s enemy blaspheming in you.

Bach’s music for this recitative is queasily unstable, with dominant-seventh and diminished-seventh chords preventing the music from settling in one key area. On the word “irreparable” the harmony lands on B-flat minor, chillingly remote from the initial G minor. It is a musical picture of wandering and banishment. Yet, Marissen concludes, this cantata is a poor vehicle for righteous anger against Jews. The aching dissonances of its opening lamentation and the peculiar instrumental elaborations in the closing chorale leave a mood of overhanging gloom, as if casting doubt on the notion that contemporary Christian sinners can escape the fate meted out to the Jews.

Marissen says that his findings have often met with a frosty reception at musicological conferences. His critics have claimed that Bach cannot be anti-Jewish, because a cantata like “Schauet doch und sehet” does not actually name Jews as enemies, and because violence against Jews is nowhere advocated in Bach’s work. These objections show a shallow understanding of the psychology of bigotry. The weakest protest holds that any noxious views are mitigated, or even annulled, by the greatness of Bach’s music. Marissen is properly aghast: “The aesthetic magnificence of Bach’s musical settings surely makes these great cantatas more, not less, problematic. The notion that beauty trumps all really is too good to be true.”

That judgment applies to the Passions, and to the St. John most of all. Of the Evangelists, John is the most vindictive toward the Jews, and many Baroque settings of his Passion narrative preserve that animus. The libretto of Bach’s St. John, by an unidentified author, is based in part on a text devised by the Hamburg poet Barthold Heinrich Brockes—a lurid treatment that was set by Handel and Telemann, among others. One aria speaks of “you scum of the world,” of “dragon’s brood” spitting venom in the Saviour’s face. Brockes’s libretto identifies the soldiers who scourge Jesus as Jews—a departure from the New Testament.

Bach’s libretto is somewhat less severe. The “scum of the world” lines are excised, and the scourging of Jesus is ascribed not to Jewish soldiers but to Pilate. Were these enlightened choices on the part of Bach or his collaborator? There is no way of knowing, but Marissen speculates that Bach, following Lutheran convention, wished to shift emphasis from the perfidy of the Jews to the guilt of all participants in the Passion scene and, by extension, to present-day sinners.

Still, the Jews retain enemy status, their presence felt in a series of bustling, bristling choruses. Many of these pieces share an instrumental signature—sixteenth notes in the strings, oboes chirping above. Several exhibit upward-slithering chromatic lines. Bouts of counterpoint create a disputatious atmosphere. All this fits the stereotype of “Jewish uproar”—of a noisy, obstinate people. At the same time, the choruses are lively, propulsive, exciting to sing and hear. When the Jews tell Pilate, “We have a law, and by the law he ought to die,” the music is oddly infectious, full of jaunty syncopations. This incongruous air of merriment conveys how crowds can take pleasure in hounding individuals. Moreover, the chorus in which the Jews protest the designation of Jesus as “King of the Jews” echoes a chorus of Roman soldiers sardonically crying the same phrase. Ultimately, Bach seems interested more in portraying the dynamics of righteous mobs than in stereotyping Jews. The choicest irony is that he uses his own celebrated art of fugue as a symbol of malicious scheming.

The Jews behave similarly in the St. Matthew Passion, where the crowd’s cry of “Laß ihn kreuzigen!” (“Let him be crucified”) is articulated as a driving, demonic fugue. Marissen highlights Bach’s handling of the phrase “his blood be on us and on our children,” which was widely taken to be a curse that Jews cast upon themselves. The St. Matthew mitigates this threat of eternal damnation with the magisterial alto aria “Können Tränen meiner Wangen” (“If the tears of my cheeks”), in which an image of dripping blood, palpably notated in the music, is transmuted into one of melancholy grace. Marissen discerns a theological message: the Jews’ curse is borne by all and, on pious reflection, turns into a blessing.

Such gestures help to explain why the Bach Passions have long found an audience far beyond Lutheran congregations. In 1824, Bella Salomon, an observant Jew living in Berlin, gave a copy of the St. Matthew to her grandson, Felix Mendelssohn, who resolved to lead a performance. His revival of the work, in 1829, inaugurated the modern cult of Bach. Although Mendelssohn had converted to Christianity, he remained conscious of his Jewish origins. The scholar Ruth HaCohen speculates that Bach’s “ecumenical, inclusive dialogue” opened a space in which Jewish listeners could find refuge. All this is reassuring, but one cannot take too much comfort. Even if the Passions lack malice toward Jews, they treat them more as metaphors than as human beings.

We pay closer attention to Bach’s texts these days because we hear them better. In 1981, the musician and scholar Joshua Rifkin offered the provocative hypothesis that the Passions should be sung not by a lineup of soloists and a chorus of dozens but by a central group of only eight voices, with a few extra voices for smaller parts. Arguments still rage around Rifkin’s proposal, but the logic behind it—having to do with the way Bach prepared his vocal parts—has won many adherents. Certainly, it has yielded crisp, bracing performances. The German words jump out at you, and the clarity of the textures accentuates Bach’s zest for dissonance. The music becomes at once more archaic and more modern.

That paradox animates John Butt’s book on the Passions. He is one of the finest modern conductors of Bach; with the Dunedin Consort, based in Edinburgh, he has made incisive, expressive recordings of the Passions, the B-Minor Mass, and the Christmas Oratorio. His version of the St. John reconstructs how the piece would have unfolded at the Good Friday service in Leipzig, with choral singing and organ pieces before and after. A Buxtehude prelude preceding “Herr, unser Herrscher” amplifies the disconcerting power of Bach’s music: you feel it thunder through the door. In “Bach’s Dialogue with Modernity,” though, Butt shows impatience with the historically minded readings favored by Chafe and Marissen. Instead, he wants to know why Bach’s works have achieved such resonance through time—how this ostensibly conservative Lutheran composer “writes music that chimes with the sensibilities of a much later age.”

For Butt, the heterogeneity of elements in Bach’s Passions engenders a novelistic richness, a virtual world rife with ambiguity: “It is as if he had entered into a ‘Faustian pact,’ by which he sought for his music an extraordinarily strong power in articulating and enhancing faith within the Lutheran religion, but in doing so gave to music an autonomous logic and referential power that goes well beyond the original purpose.” Addressing “Herr, unser Herrscher,” Butt acknowledges the theology but concentrates on the musical texture. The overlapping of strands—the circling sixteenth notes, the pulsing eighth notes, the pungent dissonances of the oboes—makes him think of human beings interacting: voices in conversation, bodies erotically intertwined. At the same time, he senses a mechanical process, a huge machine in motion. All these conflicting images spring to mind even before the voices enter.

A different kind of ambiguity arises in the solo arias, where tensions between voice and accompaniment often conjure the desperation of the beleaguered soul. The St. John Passion aria “Ach, mein Sinn” (“Ah, my mind”), a reflection on Peter’s denial, depicts a traumatized, flailing spirit. The tenor starts out in synch with the ritornello; attempts to assume an independent melodic shape; and then, failing that, tries to join up with the accompaniment again. All the while, the instruments churn through their material, indifferent to the singer’s plight. Butt calls it a “representation of a human who loses the way set out for him.”

This air of being lost in a world of ungraspable dimensions is crucial to the experience of the Passion as a whole. Above all, Butt observes, we are lost in time. In the arias and choruses, time seems to stop, as we sink into a particular emotional or spiritual condition. Elsewhere, time hurtles ahead: unpredictable harmonic schemes generate suspense at every turn of this most familiar of stories. Furthermore, Butt maps multiple time worlds, or “time zones,” in the Passions: the recitatives and dialogues, which plunge us into the midst of the New Testament narrative; the stern, stately chorales, which are like voices calling out from the era of Luther; and the arias and big choruses, which, in operatic style, show the lessons and moods of the Passion being absorbed into the Baroque present of Leipzig.

Butt relates Bach’s complex sense of time to the evolving Christian understanding of eschatology, of the nature of the Second Coming. When, after the early Christian era, the Last Judgment no longer seemed imminent, the idea of “realized eschatology” emerged: the believer could glimpse the world to come within the span of his own life. At the same time, Butt is reminded of Frank Kermode’s theory that in the modern era the concept of the apocalyptic shifts from the future into the present, into a state of “eternal transition, perpetual crisis.” In that state Bach permanently resides.

This music can be more beautiful than anyone’s, but it refuses to blot out the ugliness of the world. As Butt says, Bach’s works “agitate the listeners on one level while calming them on another.” Comfort and catharsis are not the point. For that reason, the discomfiting focus on the role of the Jews should be welcome. Bach’s vexations, his rages, his blind spots, even his hatreds, are our own. The musical literature tends to present him as a mastermind exerting uncanny control over his creations, but he, too, may have been caught in the labyrinth of his imagination. What he gives us—what he perhaps gave himself—is a way of coming to terms with extreme emotion. He does not console; he commiserates. “Herr, unser Herrscher” notwithstanding, Bach is no Byzantine deity gazing from the dome. He walks beside you in the night.

This article first appeared in The New Yorker.