A SUPERLATIVE NOVEMBER WEEKEND IN MUNICH'S NATIONAL THEATRE

On my return to Munich after a year’s absence I went on two successive nights in the first weekend of November to the Bavarian State Opera. Situated on Max-Joseph-Platz this is the third theatre to exist on this site housing the State Opera and Ballet companies since 1818. The first theatre burnt down unexpectedly, the second was destroyed by the war in 1943 the most recent neo-classical 2100 seater making it the third largest opera house in the world, after Paris Bastille and Warsaw. The house has seen premieres of many important canonical works including some by Wagner and Richard Strauss.

On Saturday 2nd November the Bavarian forces mounted a production of Beethoven’s sole opera. Originally titled by the composer Leonore to a libretto by Joseph Sonnleithner was premiered in Vienna in 1805. It was later shortened from three acts to two with the third and finalised premiered again in Vienna in 1814 this time as Fidelio.

The libretto, with some spoken dialogue tells how Leonore disguised as a prison guard named Fidelio rescues her husband Florestan from death in a political prison. It is a story of personal sacrifice heroism and eventual triumph with the underlying struggle for liberty and justice mirroring contemporary political movements in Europe. These ideas fit Beethoven’s aesthetic and political outlook.

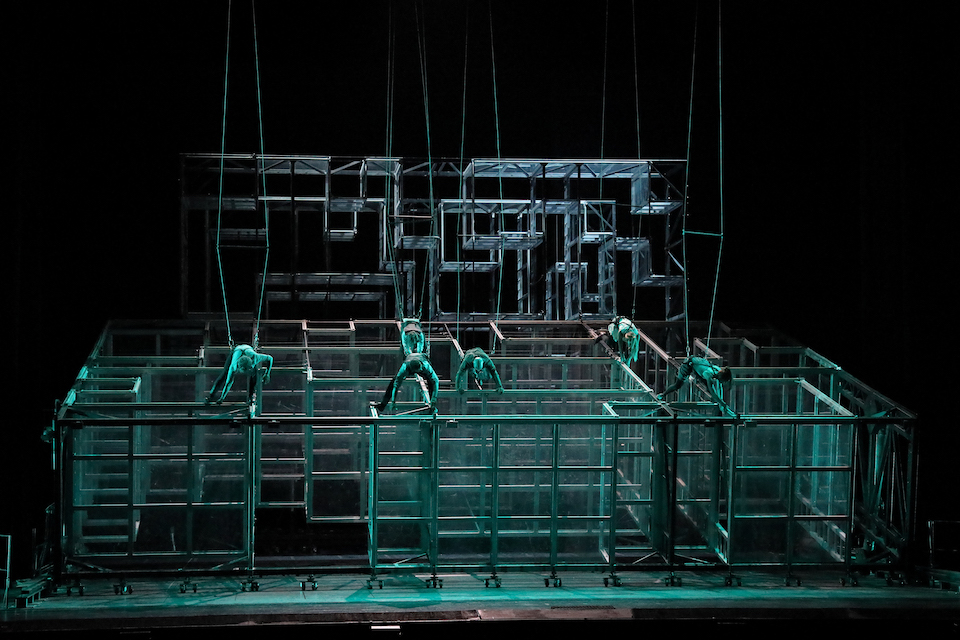

It seemed to me that this production by the Spanish stage director the operatic enfant-terrible Calixto Bieito would not appeal to everyone. The Perspex illuminated boxes symbolise the claustrophobic environment of prison cells. Zigzag lighting connoting mental distortion in the prisoner’s psyche dominated the opening. As we watched Leonore dressing as a man we were fed a monologue from her which is not in the original libretto. When the overture started it was Leonore no. 3 (1806) rather than the final Fidelio overture (1814). Another strange addition was the incorporation of the ‘Molto adagio’ from Beethoven’s string quartet in A minor op.132 between the two scenes of Act II, the position traditionally held (until about 1960) by the Leonore overture no.3. Although it was beautifully played by the Odeon-Quartett suspended from the ceiling in cages adding calmness and love to the reunited husband and wife on stage.

And what of the singing. On the night I attended Leonore was sung by Emma Bell. She is a capable singer with an appealing sound which tends to get squally at the top (the high B at the end of Komm Hoffnung for instance). Florestan was sung by Klaus Florian Vogt. He is ideal in this role with much beauty of line and musical phrasing. He also had the power to sustain long notes without ever getting harsh. A winning performance indeed. In the duet O Namenlose Freude the soprano and tenor were not equally matched. As Rocco the jailor Gunther Groissbock sang marvellously well. As his daughter Marzelline Louise Alder made a fetching youth in love with Leonore (Fidelio). The other roles were adequately sung and conductor Stefan Soltesz kept things moving despite the occasional longueurs of the production. For all those interested in modern reinterpretations of classic operas this is a must see.

On November 3rd I saw a performance of Puccini’s Tosca in Luc Bondy’s infamous ten year old production first seen at the Met. Although the staging seems now rather bland this evening was saved by some excellent singing. Angelotti sung by Markus Suihkonen although having just a few lines to sing was sonorous. The Sacristan of Martin Snell sounded woolly. Things changed immediately with the arrival of tenor Stefano La Colla who sang a splendid “Recondita armonia”. He has a bright lirico-spinto but I missed the sense of a real squillo to the top. What was specially remarkable in this entrance aria (he has therefore no chance to warm up) was the meltingly beautiful phrasing and unstrained high notes.

Star soprano Anja Harteros’ Tosca made an unimpressive entry with unidiomatic Italian. Although the tenor continued valiantly Ms. Harteros seemed uninvolved and preoccupied with merely getting out all her notes right. Thus the long love duet of Act I was disappointing. Harteros recovered ground rising splendidly to the challenges of the duet with Scarpia. Here it was the Scarpia sung by Željko Lučić who was disappointing. Although he sang in a suave cantilena there was no snarl in the voice or villainy in his demeanour.

The centrepiece Act II after the interval began with Scarpia’s monologue sung scrupulously by Lučić. Tosca enters the epitome of a jealous diva and her exchanges with Scarpia are tempestuous if occasionally uncontrolled. She sings “Vissi d’arte” the great prayer starting in a hushed voice upstage. As she reaches the audience downstage she raises her voice to a captivating climax making a huge effect. This alone was worth the whole evening.