A Romantic Recovers

Known for his melodic invention and wonderful harmonic language, Sergei Rachmaninoff’s ever popular Piano Concerto No. 2 was an act of hope and rehabilitation. By Manohar Parnerkar

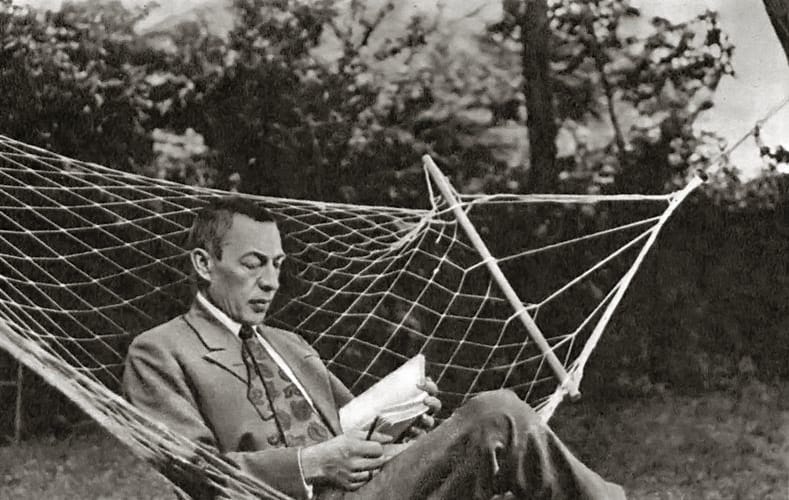

Besides being an important composer of the 20th century, Sergei Rachmaninoff was also a brilliant pianist and, potentially, a great conductor. This extraordinarily versatile Russian-born musician fled the Bolshevik revolution and came to America in 1917, later becoming a naturalised citizen. His Piano Concerto No. 2 is his most enduring work, considered by many to be the most popular concerto of the 20th century, and in good time, has also secured a prominent place in popular culture. The work, ranging in emotions from doom and gloom to joyous celebration, is a highly Romantic piece of music. But the listener may not always get a full sense of its underlying contrasting moods without knowing the background against which Rachmaninoff came to write it.

A RESURRECTION

Rachmaninoff wrote this concerto during an extremely agonising period in his life. In 1897, just four years before he finished writing this concerto, the man had been totally shattered by the critical bludgeoning his first symphony had received. ‘If there were a conservatory in hell, Rachmaninoff would gain the first prize for his Symphony, so devilish are the discords he has dished up for us,’ said one critic. The composer was engulfed by severe depression and suffered a near-total writer’s block from which it looked as if he would never recover. On a friend’s persuasion, he consulted Dr. Nikolai Dahl, a specialist in using simple hypnotherapy for the treatment of mental conditions, who interestingly, was also a lover of music and a competent amateur cellist. After Dr. Dahl’s treatment, Rachmaninoff started writing music again, and the upshot of this episode is his Piano Concerto No. 2.

This landmark work had its premiere in Moscow on 9th November, 1901, with Rachmaninoff himself as soloist and Alexander Siloti, his cousin, as conductor. The grateful man dedicated it, most fittingly, to the good doctor who had given him a new lease of life as a composer.

UNIVERSAL APPEAL

Let’s face it, Rachmaninoff was no Tchaikovsky. He considered the latter his spiritual guru and most famous compatriot, but it is doubtful if Rachmaninoff would ever rank high among all-time great composers. Why am I then commending so enthusiastically one of his works? This concerto has one happy trait in common with Mozart’s piano concertos: they both have much to offer both the connoisseur and the non-connoisseur. Perhaps, this is also the reason it came to acquire such a pre-eminent position in popular culture.

Additionally, at least a couple of the concerto’s dominant themes, supposed to be derived from Russian melodies, have an unmistakably oriental tinge. In fact, at times they sound tantalisingly close to Indian ragas – something that will resonate with many Indian listeners.

It is difficult to explain why the concerto has a special appeal to the connoisseur, and particularly to the performing artiste (it has been a great favourite with concert pianists who are out to dazzle audiences with their wizardry) without resorting to some highly technical jargon. So while describing it in detail, I will try and steer clear of the jargon, and stress on the non-technical features of the concerto’s music which have made it so popular.

THE MOVEMENTS

The concerto has three movements, each with a similar duration of around 10 to 11 minutes. The first movement juxtaposes two emotionally contrasting themes. The first theme, which is also its principal theme, is starkly grim, while the second one, shorter than the first, is lyrical. The movement opens with Rachmaninoff masterfully building up tension with some insistent hammerings of the piano. The mood of agitation which this device creates is sustained throughout the long statement of the entire first theme, and is resolved only after a quick transition into the lyrical second theme in E flat major. In the second movement, easily the concerto’s most Romantic, the flute introduces its main theme, and then goes on to weave a plaintive melody with the clarinet, leading to a dreamlike climax with a beautifully tranquil coda in tow.

The concerto’s finale, too, like its opening movement, is characterised by two contrasting themes. While the first theme, briefly introduced by the orchestra and then led by the piano solo, is full of agitation, the second one introduced by the oboe and violas is lyrical. The tension filled leitmotif of the first theme in the key of C minor does spill into the second theme, but Rachmaninoff deftly manages to end the finale in C major with a blissfully Oriental melody, which inspired Frank Sinatra’s hit song ‘Full Moon and Empty Arms’. The switching of the C minor to C major to express two contrasting emotions can only be understood in terms of a convention composers have generally tended to follow. Simply put, this convention is: keys in major scale for writing happy music and those in minor scale for music that portrays elements of drama and conflict. However, this convention does not find universal application.

Incidentally, the exuberant piano-playing and orchestration that goes with the finale’s music is reminiscent of Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto. The two Russian composers had a wonderful mentor-mentee relationship. In fact, Tchaikovsky was on the examining board of the Moscow Conservatory when Rachmaninoff was a student. Legend has it that Tchaikovsky was so impressed with the young man’s performance, he said, ‘For him (Rachmaninoff), I predict a great future.’

IN POPULAR CULTURE

Of all the great Russian composers, Rachmaninoff’s work is instantly recognised, mostly because so much of it has been referenced heavily in pop culture. In RussianAmerican author Ayn Rand’s 1943 blockbuster novel The Fountainhead, the heroes talk enthusiastically about this concerto – particularly its last movement. But it is really in movies and pop music that the work has figured extensively and prominently. The number of movies that have used the concerto’s music in their soundtracks and the pop music tunes derived from it is legion. The concerto’s main theme was used to accentuate the tragic character of a lonely ballerina played by Greta Garbo in the 1932 film Grand Hotel. In Brief Encounter, the 1945 British film adapted by Noël Coward from his one-act play Still Life, the concerto recurs throughout the film as background music. Many people who saw the film forgot about it, but got hooked on the concerto’s compelling music. In Billy Wilder’s film The Seven Year Itch (1955), Tom Ewell, fantasising himself to be a concert pianist, is shown playing this concerto with great passion to seduce the movie’s heroine played by Marilyn Monroe. In the 1954 musical film Rhapsody, a three-cornered romance between a rich lady (Elizabeth Taylor), a violinist (Vittorio Gassman) and a pianist (John Ericson) is a case of art blatantly imitating life. In the film, the pianist, suffering from severe depression, is shown performing this concerto at a concert, demonstrating that he has overcome, à la Rachmaninoff, his mental illness.

Some of the most iconic pop songs are also derived from the melodic themes of the concerto. Besides Sinatra’s ‘Full Moon and Empty Arms’, the concerto also inspired ‘I Think of You’, another of the crooner’s hit songs. David Bowie’s enigmatic 1973 song ‘Life on Mars?’ is another example. Eric Carmen’s 1975 power ballad ‘All by Myself’ is famously based on the second movement of the concerto, which, he has said is his favourite piece of music.

Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2 has had a sparkling legacy. It is recognised and beloved, not only by those familiar with classical music, but also by those who have come by it through the movies in which it has been used. Although sometimes, with astounding popularity comes occasional scepticism. After the death of the composer, the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians said that the ‘enormous popular success some few of Rachmaninov’s works had in his lifetime is not likely to last.’ How mistaken they were. The popularity of Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2 cannot and should not detract from the masterwork of the last great Romantic.

This piece was originally published by the National Centre for the Performing Arts, Mumbai, in the March 2020 issue of ON Stage – their monthly arts magazine.