A Journey Through Sound: The Transformative Compositions of Douglas Hedwig

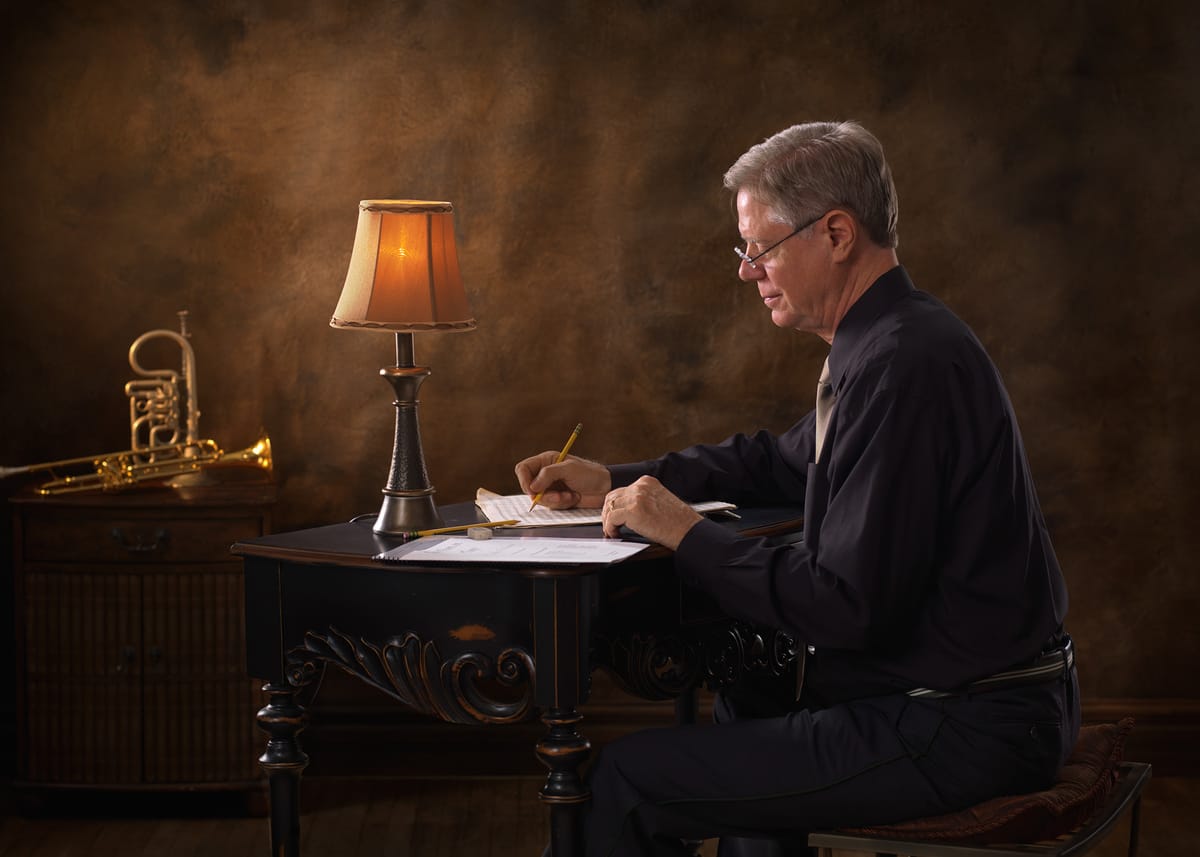

Douglas Hedwig’s life in music has been a dynamic journey from performing as a trumpet player with the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra to earning acclaim as a composer. His compositions, celebrated for their adventurous spirit and sincerity, have graced stages across the globe, from Italy and South Korea to Indonesia. A recipient of numerous accolades, including the Gaetano Amadeo Prize and an American Prize, Hedwig’s work has grown to encompass a diverse range of musical styles that bridge Western and Eastern traditions. In this interview, he shares insights into his transition from trumpet performance to composition, the profound impact of Indian music and philosophy on his work, and the joy he finds in sharing his musical voice with the world.

Serenade Team: Could you share your journey from being a professional trumpet player with the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra to becoming a full-time composer? What challenges and rewards have accompanied this transition?

Douglas Hedwig: Becoming a composer and sharing my music with musicians, listeners, and audiences around the world has been one of the greatest joys of my life; it feels as if it was always meant to be. However, my transition from performer to composer was not, at first, entirely by choice. A life-changing health event late in my career significantly altered the direction of my musical focus and pursuits. This interview is actually the first time I have chosen to speak about this publicly.

Shortly after my 60th birthday, I was diagnosed with cancer. Although the treatments successfully eradicated any traces of the cancer, the side effects left me unable to continue playing the trumpet. Following an extended period of recovery and reflection, I decided to turn the knowledge and experience I had gained over 40 years as a professional trumpet player towards something I had always secretly wished to pursue: composition. While challenging, this transition was not as daunting as one might imagine.

Throughout my career, even while performing, touring, and recording widely, I was simultaneously studying and analyzing the scores of the great music I performed. I would often ask myself, “How did these master composers work their magic?” Following the advice I frequently gave my students, I pursued my curiosity. Before the internet made scores available with a few keystrokes, I was fortunate to live just a short distance from the Performing Arts Library at Lincoln Center, one of the world’s great collections of musical scores, recordings, and archives. As the saying goes, “one door closes, and another opens.”

ST: Your work has been influenced by various musical traditions and philosophies. Can you discuss how Indian music and philosophy have shaped some of your compositions?

DH: The music and philosophy of India have profoundly influenced my compositional output, both directly and indirectly. The endlessly inventive melodic sitar phrasing of Ravi Shankar, the complex meters and rhythms within the tabla playing of Ali Akbar Khan, and the healing qualities of Gandharva Veda have captivated my curiosity and intense musical interest. In the philosophical works of Swami Vivekananda and other sages, I found inspiration to express infinity within the finite world of my compositions, regardless of style.

After a trip to India in 2015, where I spent time in Porbandar, Mahatma Gandhi’s birthplace, I felt a strong urge to integrate World Music—especially Indian music—into my compositions. My 2017 work, Movable Borders for string quintet, marked my first composition in this style, featuring an extended double-bass solo inspired by Indian vocal music.

Later works, such as Gitanjali for SATB choir, Trombone Sonata: Antarā, and Uddmāya for six trumpets, further developed this musical fusion. My first major symphonic work, Journey in 4 Movements, premiered by the Chattanooga Symphony & Opera in 2023, also incorporates these influences, with thematic and structural elements inspired by Indian music.

ST: In addition to performance, your music has been widely recognized and published. Could you tell us about some of your published works or recent recordings, and where listeners might find them?

DH: Many of my works are published and available globally. They are offered through several publishers, including Carl Fischer, Da Vinci Editions, Potenza Music, TRN Music, and Hickman Music Editions. Additionally, I am particularly proud of the positive attention my recent CD recording, Vibrant Colors, is receiving. It is available on all major streaming services, and listeners can find more about my work through the publishers’ websites.

ST: As a composer, you’ve received praise for the adventurous and sincere character of your music. Could you talk about some of the artistic values or philosophies that guide your work?

DH: Many of my compositions reflect a deep interest in a philosophy that transcends race, gender, nationality, sexuality, age, and culture. My music often draws from literature and poetry with this intent. My approach to composition reflects my study and practice of Eastern philosophy. For example, my song cycle, A Species Stands Beyond for female voice and piano, is based on five poems by Emily Dickinson, exploring a world beyond the five senses and beyond fear, desire, and attachment to success or failure.

In L’Altre Stelle for solo guitar, I drew inspiration from Dante Alighieri’s The Divine Comedy. This work is a reflection on the profound lessons of Dante’s epic, and its title, which translates to “Other Stars,” is derived from Dante’s phrase about “the Love that moves the sun and the other stars.”

Another work, New Worlds for soprano, trumpet, and piano, is a three-movement song cycle based on poetry by English philosophers John Dryden and John Armstrong, exploring transcendent experiences of space-time.

ST: You’ve taught at institutions like Brooklyn College and Juilliard. How has your experience in academia influenced your work as a composer, particularly in bridging Western and non-Western music traditions?

DH: For a few years, even while performing with the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, I lectured on Western art music history at Juilliard. This experience deepened my understanding of the Western canon and would influence my later compositions. My time at Brooklyn College’s Conservatory of Music was equally transformative. Colleagues involved in ethnomusicology and the World Music Institute introduced me to the fundamental principles of raga and tala (melody and meter, respectively). This exposure inspired me to explore these influences more deeply in my own creative work.

ST: Could you share some insights into your creative process when beginning a new composition? Do you start with a particular theme or musical idea, or does each work evolve more intuitively?

DH: This is a difficult question, as my inspiration comes from various sources and often suggests a specific compositional approach. For example, in A Certain Slant of Light for brass, organ, and percussion, I began with a four-note melodic cell that develops in different ways across five movements. On the other hand, my experimental electro-acoustic work, TransSonic Awakenings in D, was outlined in terms of architecture from the start, with a build-up that gradually dissolves into the peaceful sound of ancient church bells in Siena, Italy.

ST: Your Trombone Sonata: Antarā combines Western and Indian musical styles, reflecting the balance between opposing influences. Could you share more about the inspiration behind this piece, particularly its use of Indian musical elements like meend and the raga Aydava-shādava? What was it like working with Dr. Adam Johnson for this commissioned work?

DH: When trombonist Adam Johnson approached me for a commission, I realized that the trombone’s slide mechanism would allow for an effective fusion of Indian and Western styles. The slide enables meend (glissandi and gliding between pitches), essential in Indian music. Adam was unfamiliar with Indian music, so I sent him recordings to help him understand how it might work in context. I chose the raga Aydava-shādava for the Sonata’s second movement, a raga that resonates deeply with me. The first and third movements then fell into place, with the first movement expressing a journey toward knowledge (yātrā) and the final movement embracing rhythmic intensity typical of Indian compositions (jhala).