5 Best Symphonies by Women Composers

Museums can be magical places as they collect, preserve, interpret and display objects of artistic, cultural, or scientific significance. Exhibitions tell us stories of communities and cultures or highlight particular missions such as civil rights or environmentalism. In essence, museums are storehouses of knowledge and community treasures, and their collections are a significant resource to the community. The trajectory and educational aims of an exhibition are in the hands of professional curators, “satisfying a powerful need for community.” Given such lofty ambitions regarding community and education, the museums of classical music have done a horrible job. Curated by the big recording companies, collections and concerts have been based on exclusion and bias. Can you imagine that in 2017, music by women composers accounted for only 1.8 percent of music programmed by major U.S. orchestras? That’s an appalling and shameful statistic and a disastrous message to more than half of the world’s population. For much of the history of Western music, composition was the exclusive preserve of men. And while the symphonies by Beethoven and company are indisputable treasures indeed, there is no rhyme or reason to ignore symphonic works by women composers past or present. Classical music must foster an environment of inclusion and diversity in order to retain its place in contemporary society. And since education is an essential part of the package, we have decided to put together a representative list of symphonic compositions by women that must become an integral part of the classical music canon.

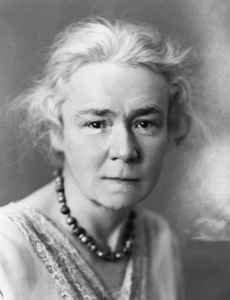

Louise Farrenc: Symphony No. 3 in G minor, Op. 36

Louise Farrenc (1804-1875) was born into a family of artists, and she took piano lessons with Hummel and Moscheles in Paris. At the age of 15, Farrenc took private lessons in composition from Anton Reicha, and her first piano works were published in the early 1820’s. She became a highly acclaimed touring virtuoso, and she was appointed professor of piano at the Paris Conservatoire, a position she held for thirty years. “She was the first woman in Europe to teach an instrumental subject as a fully qualified professor, and some of her female students became professional pianists and teachers in their own right.” In accordance with social conventions and gender-specific roles of the time, Farrenc was paid less than her male counterparts. And that inequality, as we all know, has continued until this day. However, upon the triumphant premiere of her “Nonet” Farrenc demanded and eventually received equal pay. The Parisian music critic Henri Blanchard opened his review of a subscription concert of the Société des concerts du Conservatoire de Paris in 1849 with the following words. “As an exception to their hallowed practices, a new symphony by Madame Farrenc was announced as part of the programme of the conservatory’s 8th concert.” The premiere of Farrenc’s 3rd Symphony turned out to be her greatest triumph as a composer. A scholar and conductor writes “her music reveals a level of inspiration and quality that is without equal in the Paris of the mid-19th century. She has a quite magnificent mastery of musical structures, a full understanding of the subtleties of sonata form as well as a tremendous melodic inventiveness. Thus equipped, she cultivated the art of musical expression with skill and finesse… In the way she juxtaposes strident passages with more poetic ones, she has no equal.” In her 3rd symphony Farrenc amalgamates a variety of music styles, ranging from Mozart and Vivaldi to Schubert. Her music and life is of pioneering importance, and as an audience we should demand to hear her music in the concert hall on a regular basis.

Sofia Gubaidulina: “Stimmen…Verstummen,” Symphony in 12 movements

Sofia Gubaidulina, born on 24 October 1931, has never been in doubt about her personal and musical identity and convictions. “I am a religious Russian Orthodox person,” she writes, “and I understand religion in the literal meaning of the word, as ‘re-ligio,’ that is to say the restoration of connections, the restoration of the ‘legato’ of life. There is no more serious task for music than this.” And it is this profound spirituality that informs much of her artistic process. A number of small musical symbols, primarily expressed in intervallic and rhythmic relationships, are constantly searching for deeper musical and mystical meanings. Her unique artistic language of expression is based on a composite of intuitive choices that amalgamates unique sounds and techniques within a traditional musical structure. For Gubaidulina, rhythmic ratios are not limited to local figuration. Rather, “the temporality of the musical form is the defining feature of rhythmic character.” Traditional tonal centers and triadic structures give way to pitch clusters, and chromatic space is constantly competing and reaching for diatonic space, representing a “progression from darkness to the divine.” The Soviet regime blacklisted and denounced her for producing “noisy mud instead of real musical innovation.” That kind of chastising, however, afforded her “the artistic freedom to write what she wanted without compromise.” Her approach to composition has remained fresh and unrestricted. “Whatever I write is just an attempt,” she explains, “for us human beings nothing is ever realized as we imagine. What we do is just attempts.” Gubaidulina is rightfully considered one of the most important composers alive today, and she needs to be consistently heard by audiences around the world.

Florence Price: Symphony No. 4 in D minor

Florence Beatrice Price (1887-1953) was “the first African American woman to win widespread recognition as a symphonic composer, rising to prominence in the 1930s.” She was born into a middle-class family in Little Rock, Arkansas, but moved away from the southern United States in search of new professional opportunities. The opportunity for “advanced musical training was unavailable for women of color in the South,” so she enrolled at the New England Conservatory to study organ and piano pedagogy. After graduation, she did return to the South, but escaping increased racial oppression the family moved to Chicago. Price continued her studies with Carl Busch, Wesley La Violette, and Arthur Olaf Anderson. With support of “leading figures within the Chicago Black Renaissance, Price’s works won several contests designed to support black composers.” Price achieved national recognition when she won first prize in the Wanamaker competition for her Symphony in E minor. “With the symphony’s premiere in 1933 by the Chicago SO under Frederick Stock, Price became the first African American woman to have an orchestral work performed by a major American orchestra.” Price quickly garnered attention from musical luminaries like contralto Marian Anderson, with whom she collaborated extensively. “In her large-scale works Price’s musical language is often conservative in keeping with the Romantic nationalist style of the 1920s–40s,” and we can hear some stylistic debt to Dvořák. However, her “music also reflects the influence of her cultural heritage and the ideals of the “Harlem renaissance” of the 1920s–30s. Florence Beatrice Price broke down racial barriers and greatly advanced the cause of minority women composers. She is not only a wonderful composer but also a civil rights heroine.

Johanna Senfter: Symphony No. 4 in B flat Major, Op. 50

The treatment of women in the world of classical music has been nothing short of scandalous. Take Johanna Senfter (1879-1961) as an example. Exceptionally talented she entered the Frankfurt conservatory at the age of 14 and subsequently went to Leipzig to study with Max Reger. Reger truly appreciated her “exceptional gifts as a composer” and continued to offer his protégée the benefit of his expert advice even when she was no longer officially his student. Though rigorous as a teacher, “Reger was to become an increasingly enthusiastic champion of Johanna Senfter’s work and a friend of her family.” Senfter won the Arthur Nikisch prize for composition in 1910, and as one of the most prolific female composers of the 20th century composed over 130 vocal and instrumental works. Incredibly active within the world of music Senfter founded the Oppenheim Music Society in 1921 and organized her own concert series and performances. Two years later she founded the Oppenheim Bach Society and regularly organized performances of the music of Bach. Senfter steered clear of twelve-tone and serial compositions, but developed techniques and harmonies in the late-Romantic style. She composed nine symphonies “whose formal designs reveal the influence of Anton Bruckner.” Given such an illustrious career and musical portfolio, it is inexcusable that we don’t hear her music with some kind of frequency.

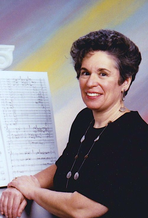

Judith Lang Zaimont: Symphony No. 4 “Pure, Cool (Water)”

Critics have called Judith Lang Zaimont “a composer worthy of broad recognition, whose high-voltage glittering works prove completely satisfying.” She started her career as a pianist, having studied at Juilliard. Subsequently, she studied composition at Queens College and Columbia University, and orchestration in Paris. Her compositions are internationally recognized and known for “a distinctive style expressing strength and dynamism.” Lang Zaimont received a 2003 Aaron Copland Award, and the 2015 American Prize in Chamber Music Composition. Highly active as a music educator, she also became a much-revered writer. Her book Contemporary Concert Music by Women, is deemed a landmark publication, and countless essay have appeared in a wide variety of scholarly journals. She was the creator and editor-in-chief of the critically acclaimed three-volume book series, The Musical Woman: An International Perspective, receiving the international musicology award. Her music is crafted in a harmonic language that is intriguing, and although the overall sound world is relatively dissonant, it retains its tonal underpinning. A critic wrote, “There is much variety of atmosphere, and Zaimont clearly possesses a keen sense of characterization, pacing, and drama.” Her 4th symphony “is a full-length orchestral work celebrating water in its naturally-occurring states—flowing, frozen, falling, still, and turbulent. Over the course of five separate movements the composer draws specific musical connections with the differing characters of this most essential resource in all its common guises.” Classical music has to be curated from a perspective of inclusion and diversity, and thus we continue our exploration of orchestral music we don’t hear everyday with symphonies by Kaprálová, Amy Beach, Lera Auerbach, Mary Dickenson-Auner, Augusta Holmès, Libby Larsen, Emilie Mayer, Alla Pavlova, Ethel Smyth, Chen Yi, and Allen Taaffe Zwilich.

By Georg Predota. Republished with permission from Interlude, Hong Kong.