200 YEARS ON: CLARA SCHUMANN

The theme for this year’s Con Brio Festival 2019 was “More Schumania: Celebrating women with Clara”. The festival showcased the works of female composers through the ages with one work by Clara Schumann each day of the festival to celebrate her bicentennial birth year. I was entrusted the task of performing her unfinished Konzertsatz in F minor completed by Dutch pianist Josef Beenhouwer. It intrigued me why Clara never finished this ambitious conception whose realisation would have been more than worthwhile.

I had often heard of Clara Schumann but it was usually related to her now more famous husband Robert Schumann and their romantic story. But when I began to research on her life, I realised it was a life of accomplishments: there are 1300 concerts recorded in her 61 year long career as a concert pianist; she was acknowledged as a peer of Franz Liszt, Sigismond Thalberg and Anton Rubinstein; in 1838 she was named “Royal and Imperial Chamber Viruosa” by the Austrian court- a distinction without precedent for an 18 year old who was, moreover, a Protestant, a foreigner and a female. For most of the century she was at the center of a circle of German musicians dedicated to preserving and continuing the legacy of what would come to be known as Western classical music.

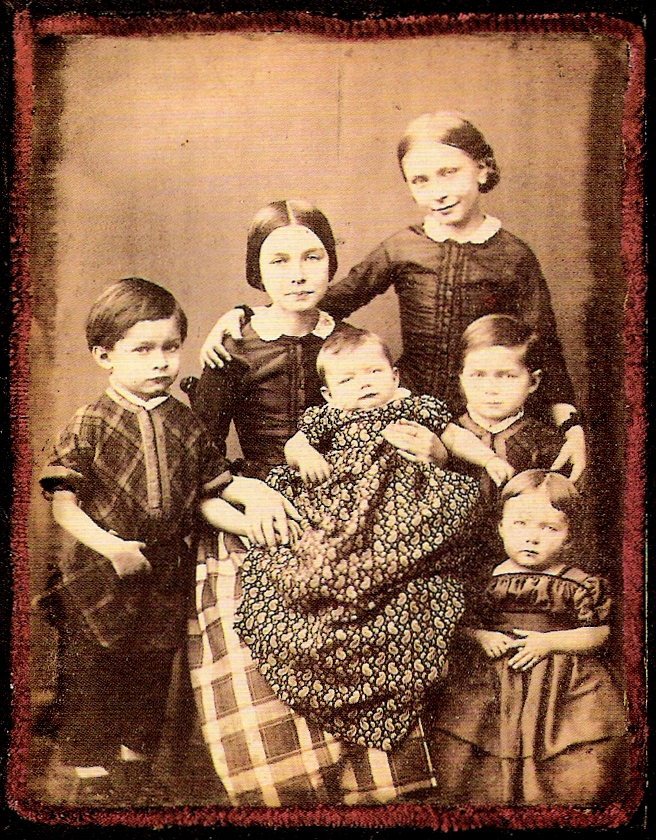

But it was also a long and difficult life of forgotten tragedies: the anguish of the break with her father, the final heartbreaking years of her husband, Robert Schumann’s life; pressures of carrying on a public career to pay for the hospitalization of a mentally ill husband and to support a family; the burden of a widow raising 7 children and deaths of 4 adult children.

EARLY YEARS

Clara was born on September 13, 1819 to Friedrich Wieck- a piano tutor and piano store owner- and Marianne Wieck, a famous singer. Her parents divorced when Clara was not even 5 years old and she remained in the custody of her father. Wieck expected that Clara would be a great virtuosa and gave her extensive training. She received daily one-hour lessons (in piano, violin, singing, theory, harmony, composition, and counterpoint) and had to practice for two hours, using the teaching methods her father had developed, largely at the expense of her broader general education. He began a diary for her and supervised her entries recording her musical activities and concerts.

At the age of 11, Clara gave her first solo concert at the Leipzig Gewandhaus in 1830 and toured Paris and other European cities to rave reviews. 1832 review in Weimar remarked:

“Even in her first piece, the artist who is still so young reaped thundering approval that mounted to enthusiasm in the works that followed. And indeed, the great skill, assurance and strength with which she plays even the most difficult movements so easily is highly remarkable. Even more remarkable is the spirit and feeling of her performance, one could scarcely wish for more”.

During her tour she played for Paganini and Goethe, who remarked “she plays with as much strength as six boys”. Frédéric Chopin spoke highly of her playing to Franz Liszt who called her a “rare phenomenon in any country”. She played frequently with Felix Mendelssohn and performed under his direction at the Leipzig Gewandhaus. In 1835, 16 year old Clara premiered her piano concerto, conducted by Mendelssohn. A Prague newspaper described her as “a member of new romantic school” linking her with “modern” composers like Chopin, Mendelssohn and Robert Schumann.

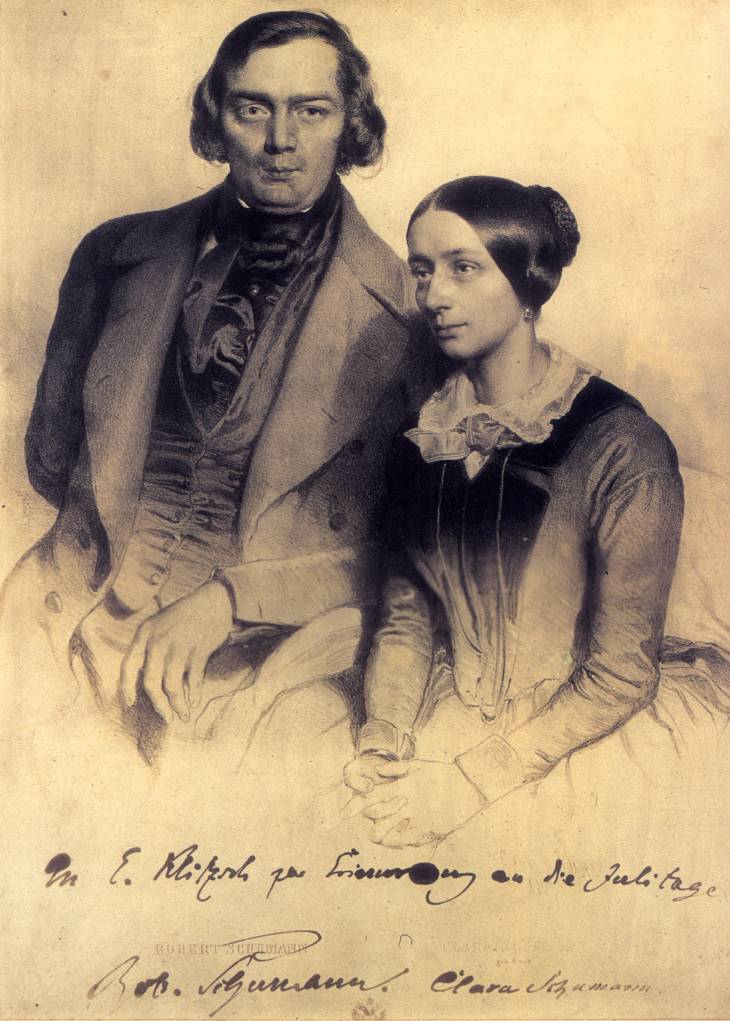

ROBERT AND CLARA

In 1928, Robert Schumann met Wieck and heard 9 year old Clara play. He admired Clara’s musicality and technical prowess so much that he asked permission from his mother to stop studying law, which had never interested him much, and take music lessons with Clara’s father. In 1830, he moved as a boarder in the Wieck household. Eugenie Schumann, daughter of Clara and Robert, recalls how Robert played with Clara and her brothers:

“He told them his best stories and played charades with them… or he appeared clothed as a ghost, so they ran from him shrieking… In this way, Robert was the biggest child of all and brought something of the sunshine of childishness to the serious life of his little friend. One can imagine how she loved him”.

With publications of his first compositions, the ties between Clara and Robert grew stronger. Right from his Papillons Op. 3, Robert looked to Clara to perform his works after he decided to focus on being a composer and gave up his dreams of a concert career. Since then, she became the foremost interpreter of his piano works. In 1837 when she was 18, he proposed to her and she accepted. Then Robert asked Wieck for Clara’s hand in marriage. Wieck was strongly opposed to the marriage and refused his permission, as he felt it would hinder Clara’s career to marry a financially unstable composer and take on domestic duties. Their famous courtship began with surreptitious meetings and secret letters. A lengthy and bitter battle ensued with Wieck dragging the young couple to court, threatening to disinherit Clara, refusing to give Clara her concert earnings and tried to malign the reputations of both Clara and Robert in musical circles. Finally, the court ruled in their favour and they married on Sept 12, a day before her 21st birthday.

Robert and Clara maintained a common marriage diary to record their problems, complaints, fears, thoughts on the music they composed, played or heard, life in Leipzig and visitors. They studied Bach fugues, Shakespeare and Goethe and poetry together. She resumed her career as a concert artist despite being a mother of 8 children and was the primary bread winner of the family. He had mixed feelings about her career. In 1837 he wrote,

“… I am often disturbed to think how many profound ideas are lost because she cannot work them out. But Clara herself knows her main occupation is a mother and I believe she is happy in the circumstances and would not want them changed”.

Still he helped publish her works and encouraged her compositions.

Robert suffered severe physical and mental breakdown which recurred in phases. After a suicide attempt in 1854, Schumann was admitted at his own request to a mental asylum in Endenich. Clara was prohibited from seeing him for 2 years to shield her from the distress she would suffer seeing him in a psychotic state and partly to shield him from reminders of the past. She was allowed to see him 2 days before his death in 1856.

BRAHMS AND CLARA

Johannes Brahms and Clara Schumann became acquainted in 1853, when Clara’s beloved husband, was struck by Brahms’s musical genius and took him under his wing. Clara inspired much of Brahms’ works and was one of the first people to perform his works. Brahms virtually sacrificed his life for the Schumann’s after Robert’s suicide attempt. He moved close to the Schumann family home to support the household and help Clara in business matters. After Schumann’s death she wrote in a letter to her children:

“…like a true friend, he came to share all my grief, he strengthened the heart that threatened to break, he uplifted my spirit, brightened my soul any way he could. He was in short, my friend, in the fullest sense of the word”

He consulted her on his creative work and she advised him on practical matters like handling his finances, salaries and investments. Though there is no evidence of a romantic affair, they shared an intensely emotional platonic relationship and were artistic collaborators for life.

COMPOSER, EDITOR AND CONCERT ARTIST

Increasing family responsibility inhibited Clara’s composition career and she stopped composing after 1856. She recognised the genius of Robert Schumann and devoted her life to championing his works curbing her own artistic impulses. In undertaking the publication of Robert’s Collective works and Instructive Edition, she preserved his work in the best way possible for future generations.

There is a famous quote by Clara Schumann:

“I once believed I had creative talent, but I have given up this idea: a woman must not wish to compose—there never was one able to do it. Am I intended to be the one? It would but arrogant to believe that. That was something with which only my father tempted me in former days. But I soon gave up believing this. May Robert always create; that must always make me happy.”

She decided that she was to be an interpretative rather than a creative artist.

Though Clara composed only 23 published opus numbered works and almost an equal number without opus number, we regard her a great composer due to the quality rather than quantity of her writing. A renewed interest in Women’s history has fuelled research into her life and works and her compositions are being rediscovered and performed with renewed enthusiasm.

As a concert artist, she programmed the works of her husband, Robert Schumann, and other contemporaries such as Brahms, Chopin and Mendelssohn in her recitals. She was one of the first pianists who made performing by memory the standard for concerts. She managed and organised her own concerts in countries all over the world including Russia, Switzerland, Belgium, France and the British Isles. She performed most often with the violinist Joseph Joachim, and singer Julius Stockhausen with whom she shared a deep friendship.

200 YEARS LATER

In 2018, Donne – Women in Music report expressed in stark statistics that across Europe, 97.6% of classical and contemporary classical music performed in the last three seasons was written by men, leaving a paltry 2.3% written by women. There have been petitions and protests across Europe to put more pieces by female composers in the exam syllabi. The majority of professional orchestra conductors are male. Blind auditions are held in major orchestras today to remove gender and racial bias.

Very often, the music of women’s composers is limited to special concerts or festivals exclusively meant to showcase works of female composers. Rather than exalting their creativity, this practice gives the impression that women composers need special assistance and their music is somehow inferior to their male counterparts. The hope is that in the future their music should be allowed to stand on its own, freely mingled and compared with music of men composers, especially their colleagues: those with whom they interact and share influence.

Today is Clara Schumann’s 200th Birthday and in honour of this occasion you might want to revisit her neglected music and pay tribute to this fine artist.

(The material has been sourced from the book “Clara Schumann: The Artist and the Woman” by Nancy B. Reich.)