The sitar, a stringed instrument revered for its rich tonal qualities and cultural significance, stands as one of the most iconic symbols of Indian classical music. This instrument, with its intricate design and historical depth, has not only captivated audiences in India but has also found admirers and practitioners around the globe. In this article, we will explore the origins, construction, playing techniques, and the influence of the sitar on both Indian and global music.

Origins and Historical Development

The sitar’s roots can be traced back to ancient times, with its evolution influenced by a confluence of different musical traditions. The name “sitar” is derived from the Persian words “seh” (three) and “tar” (string), highlighting its early use of three strings, though modern sitars typically have much more.

The instrument as we know it today began to take shape during the Mughal era in India, around the 16th century. It was during this period that the sitar started incorporating elements from Persian instruments such as the setar and the veena, an ancient Indian lute. The Mughal court musician Amir Khusro is often credited with refining the design of the sitar, although historical evidence on this point remains debated among scholars.

Construction and Design

The sitar is a long-necked instrument with a gourd-shaped resonating chamber, typically crafted from teak wood and a dried pumpkin gourd. Its structure is both intricate and delicate, featuring several components that contribute to its unique sound.

- Body and Neck: The body, or tumba, serves as the main resonator and is usually made from a large, dried pumpkin gourd, while the neck (dandi) is a long, hollow wooden tube. The upper tumba, a smaller resonating chamber at the top of the neck, enhances the sound’s depth and resonance.

- Strings: The sitar typically has 18-21 strings, divided into three categories: playing strings (usually 6-7), drone strings (chikari), and sympathetic strings (tarab). The sympathetic strings run beneath the main playing strings and resonate sympathetically, adding a shimmering, ethereal quality to the music.

- Frets and Pegs: The frets (pardas) are moveable and made of metal, allowing for precise microtonal adjustments crucial for Indian classical music’s intricate melodies. The pegs (kunti) are used for tuning the strings, with each peg controlling a single string.

- Bridge and Soundboard: The main bridge (jawari) is critical in shaping the sitar’s distinctive sound. It is carefully carved to create the characteristic buzzing tone, known as the “jawari” sound. The soundboard (tabli), a flat, wooden surface, amplifies the vibrations of the strings.

Playing Techniques and Musical Styles

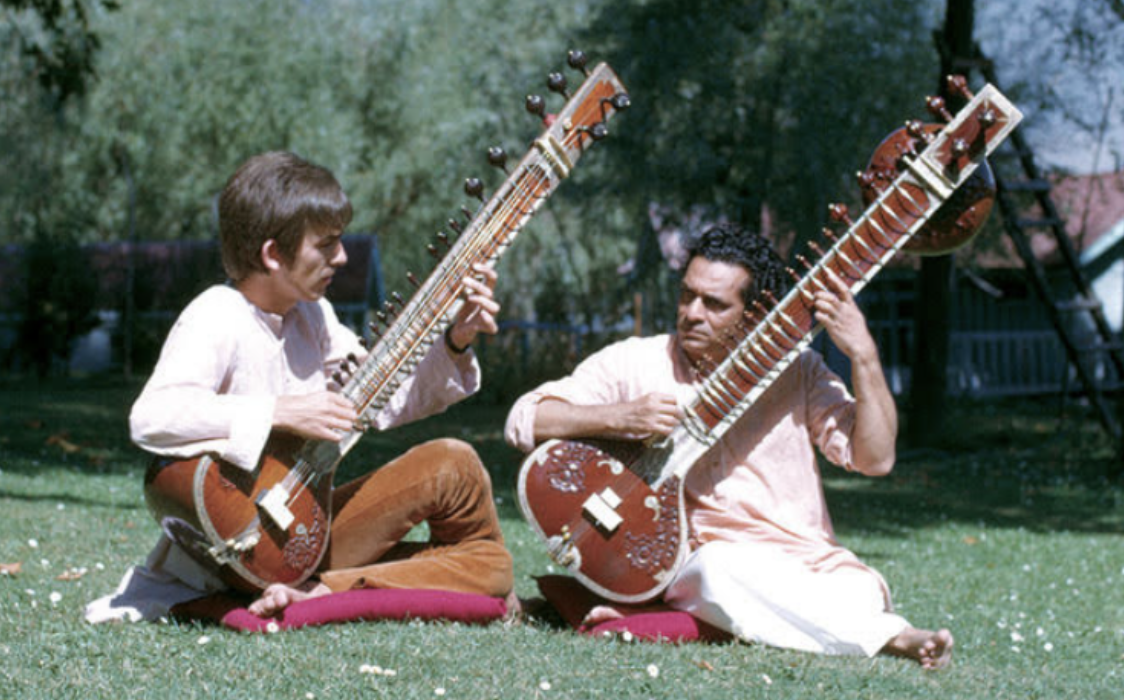

The sitar is predominantly used in Hindustani classical music, with its playing technique being both complex and expressive. The player sits cross-legged, holding the instrument at a slight angle, with the gourd resting on the player’s lap or foot.

- Right Hand Technique: The mizrab, a wire plectrum worn on the index finger of the right hand, is used to pluck the strings. The right hand technique involves intricate patterns and rhythms, known as bols, which are essential for the sitar’s rhythmic and melodic expression.

- Left Hand Technique: The left hand manipulates the strings on the frets to produce various pitches and ornamentations. Techniques such as meend (glissando), kan (grace notes), and gamak (vibrato) are used to create the characteristic fluidity and expressiveness of Indian classical music.

- Ragas and Talas: The sitar is used to perform ragas, which are melodic frameworks for improvisation and composition, each associated with specific emotions, times of the day, and seasons. The rhythmic aspect is governed by talas, cyclical patterns of beats that provide the temporal structure for the performance.

Notable Sitarists and their Contributions

Several sitar virtuosos have played pivotal roles in popularizing the instrument and advancing its technical and musical boundaries.

- Ravi Shankar: Perhaps the most famous sitarist globally, Ravi Shankar is credited with introducing the sitar to Western audiences through his collaborations with musicians like George Harrison of The Beatles. Shankar’s performances and teachings have left a lasting legacy on both Indian and Western music.

- Vilayat Khan: Renowned for his innovative playing style and emotional expressiveness, Vilayat Khan made significant contributions to the sitar’s repertoire and technique. His approach, known as the Vilayatkhani gharana, emphasizes lyrical playing and intricate ornamentation.

- Nikhil Banerjee: Known for his deep and meditative approach to ragas, Nikhil Banerjee was a master of both technical precision and emotional depth. His recordings and performances are celebrated for their spiritual intensity.

- Anoushka Shankar: Continuing the legacy of her father, Ravi Shankar, Anoushka Shankar has become a prominent sitarist in her own right. She has expanded the sitar’s repertoire by blending traditional Indian music with contemporary genres.

The Sitar in Global Music

The sitar’s influence extends beyond Indian classical music, having made significant inroads into various global music genres.

- Western Popular Music: The 1960s saw a surge in the sitar’s popularity in Western music, largely due to Ravi Shankar’s influence and the Beatles’ George Harrison. Songs like “Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)” and “Within You Without You” introduced the sitar’s distinctive sound to rock and pop audiences.

- Jazz and Fusion: The sitar has been incorporated into jazz and fusion music, with artists like John McLaughlin and his band Shakti blending Indian classical elements with jazz improvisation. This cross-cultural fusion has led to innovative musical expressions and new stylistic developments.

- Contemporary and Experimental Music: Modern musicians continue to explore the sitar’s potential, integrating it into diverse musical landscapes. Artists like Anoushka Shankar and Niladri Kumar have experimented with electronic music, world music, and contemporary classical compositions, showcasing the sitar’s versatility.

Preservation and Innovation

As with many traditional instruments, the sitar faces challenges in the modern world. However, efforts to preserve and innovate are ongoing.

- Education and Transmission: Institutions like the Ravi Shankar Centre in New Delhi and various music schools across India and abroad play a crucial role in teaching and preserving the art of sitar playing. Online platforms have also emerged as valuable resources for learning and disseminating knowledge.

- Instrument Makers: Master craftsmen, or luthiers, continue to create and refine sitars, maintaining traditional techniques while also experimenting with new materials and designs to enhance the instrument’s durability and sound quality.

- Technological Integration: Modern technology has opened up new avenues for the sitar, from amplification and electronic modification to the use of digital platforms for recording and performing. These innovations help the sitar adapt to contemporary music settings while retaining its traditional essence.

Conclusion

The sitar, with its profound historical roots and captivating sound, remains a vital and dynamic instrument in the world of music. Its journey from the courts of Mughal emperors to international concert stages illustrates its enduring appeal and versatility. For enthusiasts and musicians alike, the sitar offers a deep well of musical expression, cultural heritage, and artistic innovation. As it continues to evolve, the sitar bridges the past and the future, resonating with the timeless beauty of Indian classical music while embracing the possibilities of modern creativity.